With its history of blending cultures and accommodating newcomers willing to take the place on its own terms, New Mexico has long tolerated outsiders and refugees from mainstream America. The state’s reputation as a bohemian haven dates back at least to the artist colonies and literary circles of the early 1900s, when painters and authors seized on New Mexico as a place where they could shuck cultural bonds, try on new identities, and experiment with new artistic and social paradigms. The Taos Society of Artists, founded in 1915, the Santa Fe painters who started the Cinco Pintores group in 1921, and the vibrant salon created by Mabel Dodge Luhan in Taos in the ’20s and ’30s are only the most prominent examples of counterculture cells that experimented with unconventional living arrangements, liberated sexuality, and voluntary simplicity.

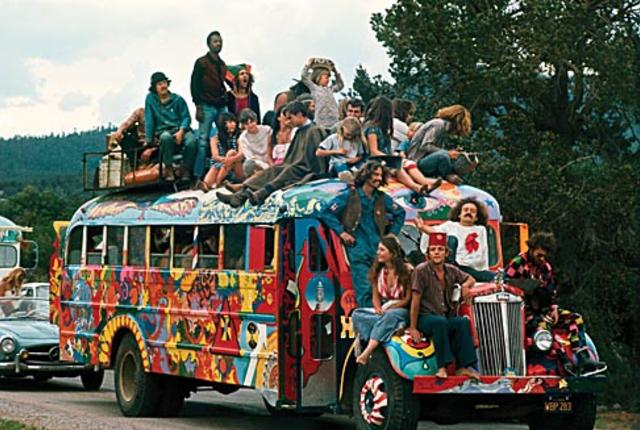

No wonder the counterculture movement of the 1960s expressed itself here in full-throated chorus. “[New Mexico] had a reputation as being an arty, spiritual place,” said one hippie habitué. By the late 1960s, according to one count, the state had 25 communes, and perhaps another dozen alternative communities. At the Woodstock festival, in 1969, the Hog Farm’s Hugh Romney, aka Wavy Gravy, took the stage and announced the group’s commune in Llano, near Peñasco. After that, New Mexico became a mecca for hippies seeking a place to “turn on, tune in, and drop out,” in the immortal words of Timothy Leary.

Although the commune era peaked in the early 1970s, many of the so-called communards and others with sympathetic sensibilities remain in New Mexico today. Key tenets of the hippie credo—back-to-the-land agrarianism, organic food, traditional healing, alternative education, artisanal crafts, solar power, and what’s now called green building—have become, if not mainstream, then at least widely accepted in New Mexico. You can see these threads in the shops around Santa Fe and the farms scattered across the state, in the home-builders associations and alternative-energy enterprises, the food co-ops and alternative-medicine schools. And many of the commune members keep the flame burning. “People ask, what was the demise of the commune?” says Hog Farmer Jean Nichols. “I’m sorry—it’s still alive!”

In this oral history, several former—and current—commune members recall the ardent idealism, the sometimes-outlandish happenings, and the day-to-day doings of New Mexican commune life.

New Buffalo

New Buffalo thrived, struggled, and survived as a commune from 1967 to roughly 1979 in Arroyo Hondo, north of Taos, enduring the complete turnover of its residents a few times. It also inspired the commune scenes in Easy Rider, though Dennis Hopper didn’t film there. Robbie Gordon, originally from the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, area, recalls the early days.

Robbie Gordon

My older brother Dave, his friend Rick Klein, and the poet Max Finstein ended up together in El Rito in 1966. Rick Klein had some money, and he said, “Look, let’s get some land,” so they scouted around and bought this land in Arroyo Hondo for New Buffalo.

After I graduated from Princeton in ’67, I got this letter from Dave written in all different color crayons on paper towels. He said, “Hey, Robbie, we’re in New Mexico forming this commune. Why don’t you come out and join us?”

So I hopped on a Greyhound, and I got off in Taos at dusk, and there’s Dave and a couple shaggy guys with a VW Microbus. We get to New Buffalo, and it’s dark, and all I can see are these trees on the hillside and these flickering lights, and suddenly a shadow shaped like a human being goes by the lights, and it hits me, Those are teepees! Dave takes me to the smallest teepee I’ve ever seen, and that’s where I spent my first night in New Mexico.

There was no structure yet. We had a kitchen outside with just a fire pit. When it rained, we’d go inside this pickup camper that was set up on posts, not on a truck. There were five or six teepees, and about 15 to 20 people there.

The communards made adobe bricks, stacked them, hoisted vigas, and built doors and windows for their new home. They moved in during November 1967, “just as it was getting cold,” Gordon recalls. “The west wall wasn’t finished, so we just stacked bales of straw to make a wall.” That wall caught fire the following summer, burning down the whole place, but Gordon says they rebuilt it before winter.

Iris Keltz

Keltz, author of Scrapbook of a Taos Hippie—a must-read if one is aiming to understand commune life—first visited New Buffalo in 1969, then returned in 1970.

The first time I visited, the initial founders were there. They had a vision. It was definitely back to the land. That’s how they took the name, New Buffalo. The land was going to sustain us [as the buffalo sustained the Plains Indian tribes]. The people who were there were writers and artists, a lot from New York. They wanted to get out of the cities.

A year later, when I came back, just about everybody I’d known was gone. Once [the members] got into a more stable relationship, a nuclear family, the commune didn’t support that. They wanted to have their own scene. The people I’d met the previous year who still lived at New Buffalo were either lost to drugs, or searching for a stable relationship, or a calling, like fishing, becoming an artist or a professional. The back-to-the-land vision was still there, although somewhat foggy.

The founders left for a variety of reasons, some because of divorce, others because they wanted more privacy for their families. Robbie Gordon left after he broke his back, thinking he could no longer productively contribute to the group effort.

Taylor Streit

By the time Streit, a well-known fishing guide who has written several books about trout fishing in New Mexico (and an article on the topic in our October 2012 issue), arrived at New Buffalo, many of the commune’s founding members had left.

When people ask how I got to Taos, I tell them, “In a turquoise station wagon that was aimed westward from upper New York State.” It was 1969. I had a girlfriend, and we ended up in Colorado in a freak fall snowstorm. We came south and saw a bunch of these weirdos and said, “They’re all like us. We must be where we’re supposed to be.”

We ended up renting a house across from New Buffalo. We were just dirt poor—no job—and I was tying flies for Sierra Sports. Then I started catching fish and trading them to the people at New Buffalo for the fine grub they had—sticks and rocks for dinner. The frugality was incredible. Beyond imaginable. We were neighbors for about a year, and I ended up living there. I procured meat. I’d go shoot jackrabbits. We ate prairie dog. There was a dedicated kitchen staff, thank God, with a lot of very motherly or domestic-minded women, very caring women. It was very much a gender-biased place. Women were in the kitchen, men went to the woods, usually without power tools, usually in some kind of half-assed vehicle like a bread van, to get firewood.

Art Kopecky

Kopecky arrived at New Buffalo in 1971 with his small band of hippie companions after traveling “gypsy style in our Wonder Bread truck” around the country. A young woman at the hot springs near the commune “invited us up and we never left.” Kopecky worked hard to reinvigorate it, and even began a family, before leaving under duress in 1979. In those years, New Buffalo continued growing much of its own food and operating what became a small-scale commercial dairy. Kopecky’s books, New Buffalo and Leaving New Buffalo Commune, provide invaluable insights into commune life.

I was really wedded to the land. Once we had some cows, I would milk them and feed the animals in the barn. I was also very involved with the irrigation. We grew green beans, chiles, acorn squash, zucchini, yellow squash, winter squash, and sweet corn. We had greenhouses where we grew tomatoes in the winter. We grew our own wheat and we had our own grinder, so we were always making tortillas. And we’d almost always be cooking pinto beans on the wood stove. We were also a hunter-gatherer people. If there had been a deer or elk killed, that would provide dinner.

Streit moved out in the early 1970s. After Kopecky left, in 1979, New Buffalo carried on for several more years before Rick Klein, who had never relinquished title to the property, reclaimed the land. He operated it as a bed-and-breakfast for several years before selling it to Bob Fies of California. Fies has substantially renovated the buildings, and today operates New Buffalo with something of the original communal spirit.

The Hog Farm

A larger-than-life figure in the 1960s counterculture scene and beyond, Hugh Romney/Wavy Gravy had been associated with Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters, of Tom Wolfe’s Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test fame, then branched off with his own cohort to form the Hog Farm in California. This commune, which settled briefly in New Mexico before moving back to California, focused on socially conscious and political entertainment—“letting the people know that they were the star of the show,” he says today, from the Hog Farm in Berkeley.

Patrick Sullivan

In California, we were hippies in the foothill area of Los Angeles when I met Wavy Gravy and [his wife,] Bonnie [Bonnie Jean Beecher, now Jahanara Romney]. We fed and cared for hogs in return for the rent. That’s how we got the name Hog Farm.

In 1968 we left California and came to New Mexico to do a Summer Solstice celebration [the first of two] in Aspen Meadows, off Ski Basin Road, above Santa Fe and Tesuque. Tom and Lisa Law took us there. We rented the area from Tesuque Pueblo for $200 for the weekend.

After the solstice, we did shows around New Mexico. We would do a multimedia show without drugs. That was the essence of the Hog Farm. We’d set up a 30-foot dome with a cover and a 60-foot, partially covered dome where my wife at the time and I projected the light show. We had a rock band, too, that traveled in the band bus, so we made a caravan as we traveled around. It was the extension of Wavy’s improvisational theater with a bigger group. That was his vision.

Wavy Gravy

We had a vision of the Southwest. The I Ching said the “Southwest furthers,” and we were going for it. Tom and Lisa Law lured us to New Mexico—and the land and the sky. We really craved it. All that time, going from state park to state park, we saw so much beauty. We first set our bead on some land in Black Mesa, but once those people saw who and what we were, they didn’t want anything to do with us. So we ended up going from campground to campground while looking for land until we found the place in Llano [in 1969].

Jean Nichols

According to Nichols, who joined the Hog Farm in New Mexico in 1968, the Llano property “had a couple houses and a barn on it. We paid $7,500 for 13 acres, with a down payment and about $50 a month in payments. Everyone just put their money together.” They moved onto the farm that summer.

We were rejecting the American Dream as it was. We thought that it was hypocrisy, the whole capitalist thing. It wasn’t “everyone is created equal with equal opportunity,” like we’d been taught in school. So we were going for peace, equality, and justice in practice. We’re all one family—everyone in the world is connected. We were trying to stop the war machine by creating a culture of peace—that was a big part of it. We were also having fun. The stereotype of the Sixties is “sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll.” There was that, but there was a lot more—good hard work. A lot of us had rejected the social mores, where you go out and get a career and live a comfortable life. So living communally was a real practical thing. We didn’t want to compete and have more than our neighbors. We wanted to live simply and with respect for the earth.

The Hog Farm’s high profile at Woodstock in 1969 would have far-reaching implications for the New Mexico hippie scene, as people flocked to Llano and other communes. “When we arrived back at Llano, it looked like a displaced-persons camp with a view—all these hippies had come to live with us forever,” says Wavy Gravy.

John Stearns

A New Mexico native, Stearns transferred from the Colorado School of Mines to the University of New Mexico in 1968. He visited several of the area communes.

Shortly after Woodstock, late September, when it was getting cold, a friend of mine and I visited the Hog Farm. My friend wanted to move there. The Hog Farm was such a compelling group—they were so visible and charismatic, you could see where they’d pick up people along the way.

We got to the Hog Farm about sunset. They were inundated with people. It seemed like 300 people were living on that [13] acres. People were cooking around the clock. There were literally lines of people in the dark waiting to get into the kitchen to get some food. I remember eating my brown-rice goulash out of a hubcap that night. People were sleeping in their cars, their VWs and pickups and school buses.

They had just built a big A-frame building and they had a meeting the next day in it—the subject was what to do with all these people, because they obviously couldn’t spend the winter at the Hog Farm. They had to get to a manageable population to get through the winter.

Jean Nichols

Wavy Gravy and most of the Hog Farmers eventually left New Mexico to work on rock festivals and pursue antiwar activism and other causes around the country. Drawn to the rural lifestyle, Nichols stayed in Llano.

I decided to stay here and take care of the land. Some of us were farmers, others hunter-gatherers. I was really into horses. A lot of people were. We thought nothing of jumping on our horses and riding everywhere. For a while, in the summers, we lived mostly on horseback in the mountains, only coming down every few weeks for supplies. We hunted and fished, tanned hides, made our own utensils, saddles, and clothes. We plowed with horses, and sometimes I’d drive a wagon down to the laundromat with all the kids.

We also had carefree days and celebrations. There was always a fire circle and people playing drums . . . the drumming never stopped. We built labyrinths, did sweat lodges, had baseball games and horse races. We delivered each other’s babies.

I guess we may have been known as the party commune—that’s what someone told me later—because we really knew how to create celebrations at the drop of a hat. And we would think of great events and celebrations around the solstices, equinoxes, the full moons, Gonk Day [in honor of the first moon landing, July 20, 1969]. On Gonk Day, we piled three TVs on top of each other so that we could watch the moon landing.

The Hog Farm ceased to function as a commune in New Mexico the early 1970s. Later, they traveled through Europe, ending up on a humanitarian mission in Nepal. They ultimately settled in California, but have kept up ties with the New Mexico contingent to the present day. Wavy Gravy and others continue to operate Camp Winnarainbow (camp-winnarainbow.org), a circus-arts summer camp for children in California. “We have a deep warm spot in our heart for the Land of Enchantment,” Wavy says. “I miss it a lot. We learned so much there. A lot of the roots of what the Hog Farm is—a piece of it is in New Mexico.” In 1973, Nichols bought the place next door partly so she could keep an eye on the Hog Farm and take care of the fields. The Hog Farm eventually sold the Llano property.

Tawapa

In 1970, several couples left a troubled commune called Lower Farm, along Las Huertas Canyon, in Placitas, to form Tawapa.

Porter Dees

In the fall of 1971, Dees transferred from Indiana University at Bloomington to UNM. He rented space in a Placitas trailer park. One day, he and a buddy went hiking to explore the area north of the village.

We found this beautiful valley and spring and this beautiful naked girl. She said, “Hi, how you doing? I live in this commune called Tawapa. Why don’t you come down and have dinner and hang out?” So we did.

The impact on me was huge. I didn’t even know how to nail a nail, at that point, so to see what these couples were doing was amazing. There were maybe five or six houses, including a round adobe with a thatched roof. This one guy, Terry, if he broke a shovel handle, he’d just head off into the hills till he found a branch on a tree that he could use, and he brought it back and fit it to the shovel. He had made this whole house by hand. They were living a totally self-sufficient life. I said, “I’ve got to be a part of this alternative life.” So I just kept going to communal dinners at Tawapa, dropping by and hanging out, and Terry said, “Here’s a spot you can build a house on.”

For my Tawapa house, Terry told me how to do a dugout, how to use the excavated dirt for the walls like rammed earth, where to get the wood at the Bernalillo mill for free, where to get the windows. I had to buy four vigas to support the roof. It had no phone, no running water, and an outhouse. Two of my buddies came out and helped me dig a hole, and we put the house around the outside. I spent about $300 on it.

It was a lovely winter. I’d get up to haul water from the spring and get firewood in the hills. That idyllic thing came to an end shortly. That summer, Tawapa was breaking up. I went to Montana with a girlfriend, and when I came back, someone was living in my house. I was probably the last one to build a house there.

At some point, someone in California published a hippie map showing where the communes were, and people just came to Tawapa in droves. They’d camp. The folks who started coming were way more into drugs than we were, and ruined it. The core group was gone by ’72. Everyone started scattering. I gradually started getting back [to conventional life]—I got a job, went back to school—but I stayed in Placitas.

To me, it was idyllic. I wish it had lasted longer, but it was kind of the end of an era. That era was probably the happiest time of my life.

Charles C. Poling is a New Mexico-based writer.

Santa Fe–based photographer Lisa Law’s career has spanned five decades and includes musicians, actors, artists, and other figures from Haight Ashbury to the Woodstock festival to the New Buffalo Commune. She hopes to open the Lisa Law Museum of the Sixties in Santa Fe. See more of her work at flashingonthesixties.com.