Above: Sunrise Springs' 20 Silkie chickens are getting some special attention from staff without visitors to the resort. Photograph courtesy of Sunrise Springs.

WHILE WE'RE ALL COOPED UP AT HOME, dreaming of where we hope to go when it’s safe to travel again, some people are hard at work ensuring the places we love are ready to greet us when that time comes. They’re using these quiet weeks to tackle projects that have been put off or couldn’t be done with a steady stream of visitors and sharing the workload in surprising ways. In short: Don’t worry. It’ll be there to go back to, better than ever.

Springs Heal

Each morning, Chris Niederschulte arrives to work as general manager for Sunrise Springs near Santa Fe, sits down with the 20 Silkie chickens that live at the resort and checks his email. “You can go in, hold the chickens, play with them, and they give you a sense of peace and rest and happiness,” Niederschulte says.

To provide calm for guests, the chickens need to feel comfortable around people. Typically, they’re visited often enough by guests that it’s not a concern. “It kind of falls on myself and the grounds staff, whoever is here on property, to essentially visit them to make sure that connection with people is there,” he says.

The Silkies run up to him when he walks into the coop, rub against his legs, and enjoy snacks of salad leftovers and weeds pulled from the gardens.

It’s one of several duties spread among those still working at the resort. The 70 acres have bustled with activity as staff trim trees, plant flowers, clean ponds, fill greenhouses with seedlings, touch up paint, deep-clean carpets, fix irrigation lines and landscaping machinery, and make sure the natural spring that feeds Sunrise Springs’ pools is capped correctly, pausing its flow. The pools themselves have been drained and resurfaced, and finishing touches were made on a new soaking pool.

“We are all pitching in together—so many people are wearing multiple hats,” Niederschulte says. “The silent thing that’s happening is relationships are being built, because you would have never had the time for that before. It’s pretty remarkable.”

Farther north, at Ojo Caliente, General Manager Chris Dutkiewicz says he’s waking up nights with new ideas for how to transform the resort to meet the “new environment of hospitality.” Expect to be greeted by a remodeled, more expansive lobby and a streamlined check-in. With the resort closed, the pools are empty and staff are re-plastering their surfaces, removing mineralization from pipes, adding in-pool lighting, and resurfacing concrete.

Water reaches most pools from valve-controlled pipes leading from separate storage tanks, but not so with the popular “Iron Pool,” in which mineral water flows up through that gravel floor. Because it’s a favorite, it’s a tough one to close for lengthy maintenance, says Nick Wimett, projects and engineering manager. They’re using this time to re-do its benches, set new stones, and pave over a little more of the floor. Routine cleaning includes draining and pressure-washing the mineral pools every other night, which involves sucking the gravel off the floor of the “Iron Pool” so it can be scrubbed, a task that keeps staff working until 2 a.m. The goal is to reduce some of that time.

“In some ways, the pause has been great, because now we can take a breath and say, ‘Okay, this is what we really need to work on,’” Dutkiewicz says.

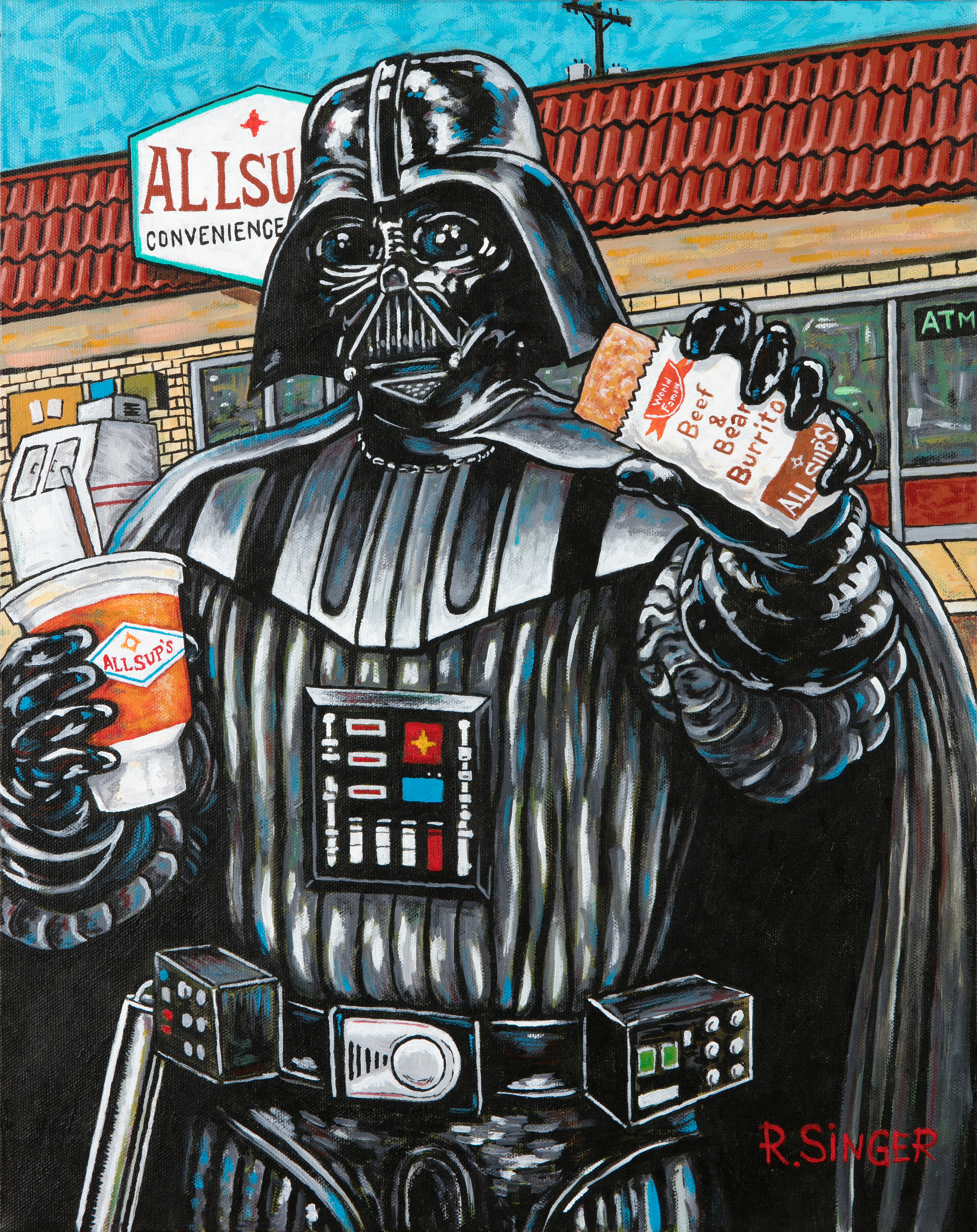

Above: Ryan Singer's work blends pop culture and his experience growing up on the reservation. Photograph courtesy of the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian.

Remote Access

Even with doors closed at the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian, in Santa Fe, curatorial staff wanted to expand access to the collections. The museum had begun incorporating “guide by cell” technology, which allows visitors to turn their smartphones into an interactive tool for exploring exhibitions. Call a phone number to hear a recording of a curator or an artist talking about a piece of art.

“The pandemic allowed us to focus in on those things that would allow us to connect to that audience who couldn’t come to visit us,” says Chief Curator Andrea R. Hanley. “But to me, being Navajo, it’s an issue of connectivity. Some people don’t have laptops and some people don’t have good internet connectivity. So some people are doing everything on their phones.”

Instead of launching web-browser platforms, they aimed for phones. Text “wheelwright” to 56412 and a webpage loads with a list of exhibitions to explore, including pieces from LIT: The Work of Rose B. Simpson, the Santa Clara Puebloan’s ceramic and mixed media sculptures, and From Converse to Native Canvas, a collection of beadwork sneakers. An exhibition people just “glimpsed” before the closures, Hanley says, has been revived at a time we need its reminders most: Laughter & Resilience. (Desktop complements are available, including coloring sheets.)

“We’re just trying to reach people in a completely different kind of way that maybe makes them laugh or teaches them about an exhibition or an artist in a way that isn’t really a straightforward interview and maybe catches their eye,” Hanley says. “It’s all about connecting with our audience and making sure people can kind of take a break and look at things and maybe look at things in a different way.”

Above: Agapita Lopez oversees Georgia O'Keeffe's Abiquiú house and studio, which is receiving some improvements while closed to the public. Photograph by Stefan Wachs.

Above: Agapita Lopez oversees Georgia O'Keeffe's Abiquiú house and studio, which is receiving some improvements while closed to the public. Photograph by Stefan Wachs.

O’Keeffe Anew

Given the constant visitor traffic at Georgia O’Keeffe’s Abiquiú house and studio, caretakers could do no better than watch the mud-plastered floor in the hallway connecting the garden and patio deteriorate back to dirt.

Any task that involved moving furniture or shutting down part of the house didn’t work with the half-dozen tours each day, says Agapita Lopez, who oversees the house and previously worked for O’Keeffe. Now, with no one visiting, they’re ticking through a to-do list of projects at her house at Ghost Ranch and the one in Abiquiú.

“It is an old home, so like any old home, there’s always something to do,” Lopez says. “That’s what’s great. It keeps us busy and moving forward and thinking ahead, and looking into the future.”

She and her staff—while keeping a social distance—have repaired windowsills and window frames, painted walls, and restored those mud-plaster floors.

“This would have been how Ms. O’Keeffe would have had it,” Lopez says. “We continue to try to keep the house very much as if she were still to come back.”

Of note is how workers restored a gate to a style that matches what was present during O’Keeffe’s lifetime, as recorded in a Tony Vacccaro photo of her standing by it in the 1960s. Staff have also planted peas, chives, and onions in her vegetable garden. Chile and tomato plants are on the way from friends at local greenhouses. The herbs are coming back up, especially mint. This spring’s blooms of lilacs and forsythia have come and gone, but the roses, peonies, and hollyhocks are still just budding, and may soon greet visitors.

Above: The Museum of International Folk Art’s Multiple Visions diaramas are getting cleaned and photographed by staff. Photograph by Kitty Leaken.

Above: The Museum of International Folk Art’s Multiple Visions diaramas are getting cleaned and photographed by staff. Photograph by Kitty Leaken.

Dust Busters

The Museum of International Folk Art’s flagship installation is a 10,000-square-foot display of dioramas—and they get dusty. In 1982, artist and designer Alexander Girard created Multiple Visions: A Common Bond, an installation of miniature scenes from everyday life around the world. Well over a million visitors have strolled through its displays of a Chinese opera, a christening, a Pueblo feast day, a Mexican kitchen, a Victorian town, and an Italian villa complete with boats.

“It’s like a time capsule to a different period of how we interpret other cultures,” says Director Khristaan D. Villela. “We do great exhibitions, but the Girard wing is a permanent display and it’s a real experience.” (Not familiar? A Google 360 tour is among the museum’s online resources.)

Multiple Visions inspires repeat visits, so the museum was always reluctant to close it for cleaning. But since the museum itself is closed, staff have changed out plexiglass cases, updated lighting, and cleaned and photographed the displays, some of which include more than 200 pieces. The process involves cleaning each tiny piece with a museum-standard vacuum designed for removing dust from objects. Then each piece gets an individual photograph in a studio set up right in the wing. When every piece in a diorama has been photographed, it's returned as Girard originally set them.

“It looks terrific now, but it has been a tedious process,” Villela says. “It’s a good thing to undertake when the museum is closed.”

True Hero Shout-outs

At some of the other destinations around the state, no one gets much downtime. Staff at the New Mexico Farm and Ranch Heritage Museum, in Las Cruces, have had their hands full caring for four Navajo-Churro lambs born in April, adding fencing and a new play structure, and relocating a windmill. … At the Very Large Array, near Socorro, scientific observations have continued as an essential service, with a skeleton crew and special precautions taken.