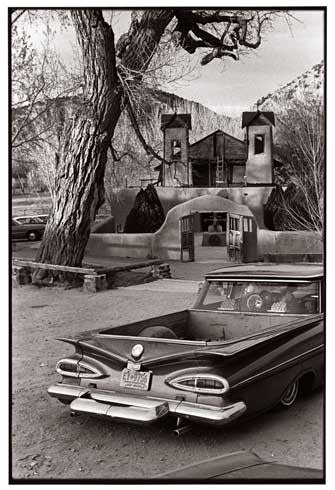

Holy Thursday, El Santuario de Chimayó, 1982. From Look into My Eyes: Nuevomexicanos por Vida, ’81–’83.

Holy Thursday, El Santuario de Chimayó, 1982. From Look into My Eyes: Nuevomexicanos por Vida, ’81–’83.

INTERGENERATIONAL KNOWLEDGE is common enough among New Mexicans, like the smell of fresh green chile stew and homemade tortillas in any gramita’s kitchen, with Al Hurricane singing through a radio in the background. It’s just part of life. You wake up to it and breathe it in throughout the day. You hear it without listening sometimes. If one word could capture the multiple sensations it evokes, it would be comfort.

In many instances, intergenerational knowledge is transferred from one New Mexican to another through cuentos, or stories. Sure, there are dichos (sayings) and chistes (jokes) that slip off the tongue every now and then. But try to remember: When’s the last time you heard a good little story? It was probably the last time you ate dinner with your relatives, those viejitos who message their grandchildren over the “wee-fee” connection yet still prefer having face-to-face conversations about things como había antes, how they were before, usually with eyes open to the future. I don’t think it is an exaggeration to say most older New Mexicans like to tell stories, and that the young people—not always, but often enough—like to listen.

The stories help us make sense of the world and our place in it. They help us connect with the living and remember the dead, so we are never alone. They offer wisdom accumulated over years and years of experience. New Mexicans have stories for everything, from the food we eat to the rock formations we see on the roadside. I often feel that there is something about the homeland, our Nuevo México, that calls to us and demands our stories.

I remember taking many car rides with my mom and dad from Santa Fe to Cebolla via Highway 84 as a child, when my dad would share what his tío Casimiro used to tell him about places such as the Echo Amphitheater and Mesa de las Viejas. Tío Casimiro’s knowledge and experience, along with what I’ve gleaned from my ancestors, or antepasados, have given me a deep love for my home state, which I’ve only come to understand recently. The scholar Enrique Lamadrid has a word for this experience, the way we feel connected to a particular landscape and community: querencia.

In an interview with Jack Loeffler (“For the Love of La Musica,” January 2015, mynm.us/nuestra_musica), Lamadrid described querencia as “a sense of rootedness. Querencia is the place where you know you belong.” The feeling tends to be so strong that people “who are from New Mexico want to be in New Mexico. If they’re not here, they’re trying to figure out how to come home. Querencia means all of those things. It’s a place that you love. It’s the place you want to be. It even has the sense of the place you want to die in.”

I am a 25-year-old nuevomexicana who has spent the past three years of my life hundreds of miles away from my home, a distance that has only made my querencia grow stronger. I moved to Houston, the fourth-largest city in the United States, to begin graduate school. I’ve gotten used to the hustle and bustle, the dank air, and feeling like I never have enough time to write and read and learn as much as I should at any given moment. I still haven’t shaken my homesickness completely, but letters and boxes from home keep me satisfied.

I remember receiving my first care package from home in mid-October. My parents sent me a large USPS box filled with bags of powdered red chile, dried posole and chicos, apples from Velarde, pressed flowers from the chamisa, and several clipped newspaper articles, including one about a lowrider show in Española. (What can I say? My parents understand me.) That night I set out the slow cooker with pork and posole. I recall waking up the next day with a better sense of clarity and optimism. Memory after memory, story after story, unfolded in my mind. The warm cooking smells alone had made me feel that much closer to mi estado querido.

Moments like these help me understand the complex beauty that comes from cuentos and querencia found in the writings and poetry of authors like the late Sabine Ulibarrí from Tierra Amarilla. Ulibarrí’s poem “Nuevo México Nuestro,” for example, is about the circular nature of life and the ways folk practices and place work together to play a crucial role in finding one’s way. In the poem, the land, or tierra, doesn’t just serve as ground for one to walk on; it is an active force that bears witness to who we are, just as it shapes how we live:

Tierra que me vio nacer,

Land that saw my birth,

me ha visto vivir

you have seen me live

y me verá morir,

and will see me die,

me enseñó a querer.

you taught me how to love.

Tierra llena de risa,

Land full of laughter,

de llanto y encanto,

of weeping and enchantment,

de promesa y desencanto,

of promise and disenchantment,

de rosas y de espinas.

of roses and thorns.

Toward the poem’s end, the land takes on the voices belonging to the antepasados:

Muchas veces en la brisa

Many times in the breeze

de alguna noche tranquila

of some peaceful night

hay susurros y murmullos,

there are whispers and murmurs,

y suspiros imprecisos.

and unsettled sighs.

Son las voces de los viejos

They are the old ones’ voices

que perduran en el viento.

that survive in the wind.

Tienen tanto que decirnos

They have much to tell us

para el tiempo en que vivimos.

for the time in which we live.

This poem went unpublished during Ulibarrí’s lifetime. I found out about it when I stumbled upon a short New Mexico PBS video on YouTube titled “A Mi Raza,” where he recites “Nuevo México Nuestro.” It’s worth taking the time to watch.

Reading and writing about Chicana/o literature at Rice University has led me to a closer understanding of the relationships that have been so formative in my life up until this point. Last summer, I had a conversation with several professors and graduate student colleagues that made me appreciate the knowledge I’ve accumulated by sitting among my elders while they told stories about the past. We were talking about how people in late-19th-century and early-20th-century California might have kept food cold without iceboxes or refrigerators. I admitted that while I knew little about people’s habits in California, I knew that New Mexicans had dirt cellars called soterranos, which kept fruits, vegetables, and meats cold and dry through the warmer months. There’s still one partly intact behind my grandparents’ old house.

“You know a lot,” one of my professors said in a tone that was somewhere between admiration and surprise. (This is probably the only time I’ve received such a compliment in graduate school.) “I listen” was all I had to say in response. This was an unusual moment in an environment where listening is valued much less than having a hard-line argument about every topic, where ideas worth knowing, we tend to assume, come from years spent in isolation, bent over books about what constitutes literature.

I used to think that my family’s stories about the way things were, como había antes, would have little effect on my life, but they mean everything to me, especially now that I live so far from home. So I say to the viejitos in New Mexico: Continue talking and continue teaching. Todavía tienen tanto que decirnos para el tiempo en que vivimos. There is still so much for you to tell us for the time in which we live.

—Elena Vicentita Valdez is a doctoral student at Rice University.

WHAT DOES ‘ONLY IN NM’ MEAN TO YOU?

Submit your contribution with name and mailing address to onlyinnm@nmmagazine.com, or mail to Only in NM, New Mexico Magazine, 495 Old Santa Fe Trail, Santa Fe, NM 87501. Submissions will be edited for style and space considerations.

Want more like this? Subscribe now!