When I was young, my family lived on the Bacone College campus in Muskogee, Oklahoma. Every Sunday after church, we visited the Five Civilized Tribes Museum, and I used my modest allowance to buy small prints and cards of work by local Native artists—my entrée to art collecting. That curiosity eventually led me to the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA), in Santa Fe, which I attended in 1995 after working for many years as a bike messenger in San Francisco. There I studied two-dimensional art for just two semesters, when it was still located in the “Barracks” on the old College of Santa Fe campus. From 1996 onward, until I moved back to New Mexico, I split my time between San Francisco and Oklahoma. I craved extremely broad experience in my field, and moving around was a necessity, in order to be exposed to the widest possible range of viewpoints and perspectives on mainstream and Native art. And yet, what I experienced along the way ultimately drew me back to Santa Fe.

You see, in grad school at the San Francisco Art Institute, students and some instructors kept exhibiting what I call The Wall—an absolute unwillingness to engage with Indigenous subject matter. The Bay Area has no shortage of romantic notions about Native Americans, but the persistent stereotypes in the local art scene were: Indians are tragic. Indians are dead. Indians are completely irrelevant to the contemporary world.

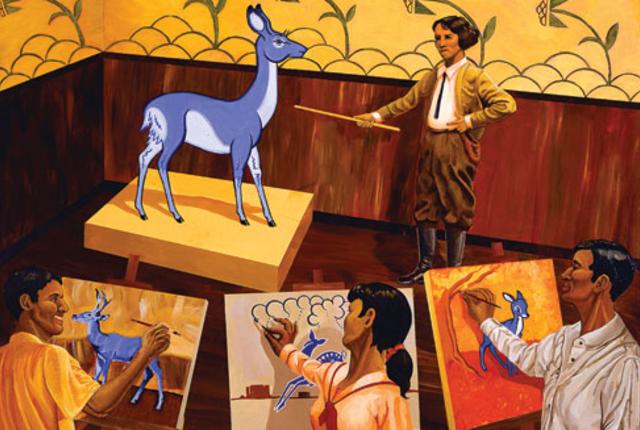

A perfect example of these misperceptions is the initial reaction to my painting Bambi Makes Some Extra Bucks Modeling at the Studio, which I painted and first exhibited in San Francisco. The work centers on art teacher Dorothy Dunn (1903–1992), who taught in the Studio at the Santa Fe Indian School. Dunn, whose students included giants like Allan Houser, Harrison Begay, Pop Chalee, Quincy Tahoma, and Pablita Velarde, was a controversial figure who moved Indian education away from assimilation, while forcing on her Native students one particular style of painting. There is a blue deer in the painting—a reference to “Bambi Art,” the derogatory term for the Flatstyle Native American painting that Dunn taught to her students.

Taos Pueblo artist Pop Chalee sold several of her paintings of stylized blue deer to Walt Disney prior to his studio’s release of the popular animated movie Bambi, hence the style’s nickname. Mid–20th-century non-Native “Indian art experts” heralded Flatstyle painting as the only authentic form of Native American painting, and rejected more experimental Native art from exhibitions. Thankfully, the 1962 founding of IAIA in Santa Fe signaled an end to the constraints of Bambi Art.

My Bambi painting was not just another piece of Bambi Art, but rather a comment on Dunn’s influence and the art world’s (critics’, mostly) ignorance about the deer’s important cultural and symbolic meaning. In Huichol cosmology, the blue deer, named Tamatsi Maxayuawi, is the elder brother of humans. Huichol religion influenced that of northern tribes through peyote religion and the Native American Church, to which many of these Flatstyle artists belonged. Non-Native art writers belittled the blue deer and so-called Bambi Art in the late 20th century, oblivious that the blue deer was very significant to Native peoples. Dismissing Bambi Art as a mere stylistic choice was like dismissing a culture’s belief system.

My Bambi painting garnered negative criticism from well-meaning yet naïve critics in San Francisco. But when Bambi showed at the IAIA Museum, in Santa Fe (now the Museum of Contemporary Native Arts), everyone got it. Former IAIA Museum director and faculty emeritus Chuck Dailey pointed out that the stick in Dorothy Dunn’s hand was real—and that she used it to hit students who didn’t paint the way she wanted them to. Still, Dunn encouraged many Native artists who ultimately found their own styles. And then it dawned on me: Santa Fe was the place where challenging, nuanced work could be respected. The city’s location and ancient Puebloan history meant that many people there already had a deep connection to Native art and culture.

This became almost painfully clear to me the first time I participated as an artist in the Santa Fe Indian Market. I remember feeling a little cocky about how complex my work was. I had a gouache painting of a Maidu dancer covered in pelican feathers, wearing a coyote headdress. (I’m much more careful and deliberate about cross-cultural appropriation now.) Several times I launched into a rehearsed explanation of a historical figure in a painting—only to discover that a visitor to my booth was related to the subject!

My Bambi painting was also part of Native Pop, a 2006 exhibit at the Museum of Fine Arts (now the New Mexico Museum of Art). Native Pop was shown in conjunction with Pop artist Roy Lichtenstein’s work inspired by Pueblo pottery. As an art movement, Native Pop doesn’t just randomly incorporate any mainstream imagery; artists strategically use instantly recognizable icons as allegories and entry points to their work. Here again, Santa Fe got it. The amazing exhibit demonstrated once again that my work, and the work of other Native American artists, was taken more seriously in Santa Fe than in other U.S. art cities.

Now, New Mexico is my home. It’s the crossroads of Native American art in this country. It has been for centuries. And Santa Fe is the Native artist’s New York City. People understand the work, there’s a demand for the work—and there is no Wall. ✜

Santa Fe–based artist and curator America Meredith is an enrolled member of the Cherokee Nation. She is also the editor and publisher of the new First American Art Magazine, which is devoted to exploring the art of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas from a Native perspective.