Above: The National Scouting Museum. Photographs by Gabriella Marks.

I'M IN A ROOM FILLED WITH TREASURE. Some of it has passed through generations, some crossed continents. Some came from attics and backyards, some was dug up from the earth. Some, I note by the box labeled SPACE HELMET, traveled from even farther away.

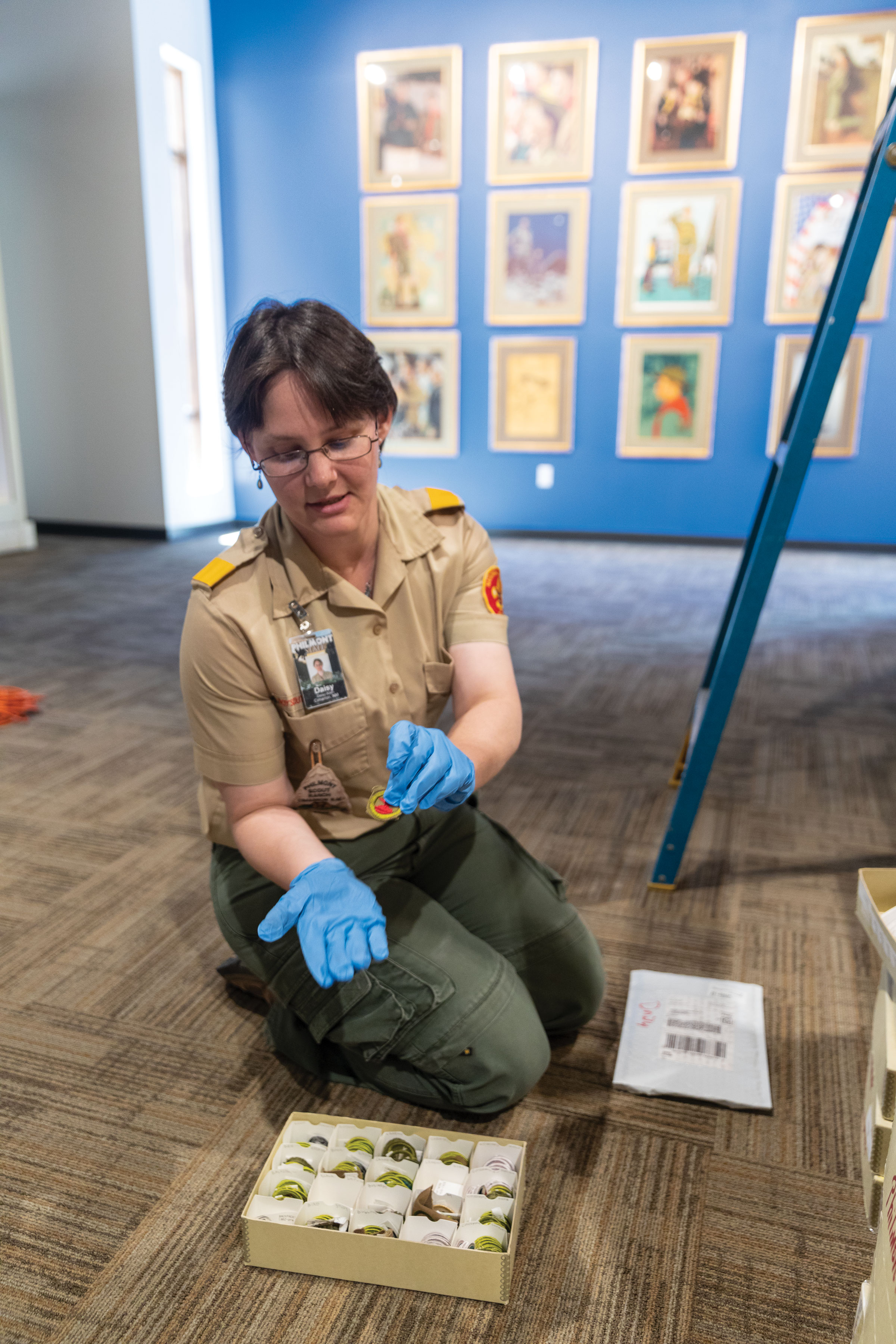

Daisy Allen, the collections curator at Philmont Scout Ranch, just south of the small town of Cimarrón in northeastern New Mexico, opens this last one and gently removes the broad white helmet, holding it out for me to admire. Then she pulls a pair of boots from a second box. Stylishly aerodynamic, they have rounded edges and treads that curl up over the sides, and—stop me if I’ve said this before—they’ve been in outer space! Now they’re here, at the Philmont Scout Ranch.

The reason for that is simple: The astronaut who wore them, James Lovell, was an Eagle Scout, the highest rank attainable in the Boy Scouts. And this September, Philmont Scout Ranch, run by the Boy Scouts of America (soon to be renamed Scouts BSA), will become the new home of the National Scouting Museum. It’s a big deal, elevating Philmont even higher among Scouting aficionados and carrying more of its lore to the general public.

Every summer, Philmont is the high-adventure dream of loyal, trustworthy, and brave boys and girls from around the country. More than 20,000 Scouts, Venturers, Sea Scouts, and Scout Leaders come here to live out the Scouting story even as they add to it: a story of spirit and inspiration, of learning, of being outdoors, of helping others, of families, society, and civic duty.

To be a Scout at Philmont is to experience the slow, stoic presence of nature, powerful but reserved, at once accessible and intimidating, in a place of rugged beauty and peaceful solitude, splendor, and serenity. Cradled in the foothills of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, the ranch lies in the transition zone between the Rocky Mountains and the prairies that stretch forever eastward. Deer wander the buildings of the base camp; turkeys take their time crossing the roads, because they know you’ll stop for them. The wrinkled slopes of the nearby mountains appear like aged faces freckled with piñon and juniper trees on the lower slopes and ponderosa pines and aspen on the upper. Of all of them, the sun seems to have a particular fondness for the spire known as Tooth of Time, striking it sharply throughout the day, bringing its sleek, prominent peak into bold relief. It’s a special place, Philmont. A place where your soul can take a deep breath.

And this month, it also becomes the backdrop for the museum that honors and celebrates Scouting. At least part of the Scouting story can be told through the memorabilia that has accompanied it, and that’s the responsibility the staff at the museum is taking on. It’s not an entirely new task. Philmont has long had a museum, which included items of Philmont and other local history, as well as pieces from the collection of naturalist Ernest Thompson Seton, one of the founders of the Scouts, who spent much of his life in New Mexico. By coincidence, museum staff were already undertaking a construction project to expand their museum when they got word in December 2016 that the National Scouting Museum, previously located in Irving, Texas, would move to Philmont. They expanded their expansion and began sorting, cataloging, and selecting display items from three semitrucks’ worth of boxes: canoe oars , backpacks, Boys’ Life magazines, crafts, manuals for every level of the Scouts, including the Lone Scouts (a program for those who live in rural areas or who otherwise cannot join a troop), uniforms, and one space helmet with boots.

Daisy shows me another treasure, one that’s more down-to-earth: the first Eagle Scout award ever given, back in 1912, two years after the Boy Scouts of America was founded. Its ribbon is a bit worn, but I hope I look that good when I’m over a hundred years old. She shows me a photo of the boy who received it, 16-year-old Arthur Eldred, from New York. While Eldred was nominated as an Eagle Scout on August 21, he had to wait two weeks to receive his award, because it hadn’t been made yet. I ask Daisy what she likes best about working with all these objects. “I get to hold them,” she says.

Want more stories like this delivered to your door? Subscribe today.

“BE PREPARED” IS THE SCOUTS’ MOTTO, which was put to the test in June. The Philmont summer staff had arrived only weeks before when fire broke out near Ute Park, roaring across 37,000 acres and destroying a dozen Philmont buildings—none of them occupied or critical to the Scouting program. Thankfully, the summer programs had not yet begun and no Scouts were at the camp. Philmont teams accounted for staffers scattered across the property and transported them back to base camp. Upon a decision to evacuate, they were shuttled to the fairgrounds in Springer, some 30 miles away—all 1,100 of them in less than two hours. In early July, Philmont announced it would cancel its remaining summer programs due to the ongoing “extreme” fire danger in the area.

The news was another challenge to an organization that has undergone several recent transformative changes. In an effort be more inclusive, the Boy Scouts are adopting more than just a new name; they’ve also expanded their outreach to gay and transgender youth and will soon admit girls into the Cub Scouts and Boy Scouts (Girl Scouts is a separate organization). Now more young people will be able to glean Scouting’s benefits and become part of its mission, its history—and its museum. (It’s worth noting, however, that Philmont itself has long been coed: Exploring and Sea Scouts, among other Scouting programs, already admit girls, and young women have been coming to Philmont since the 1970s.)

Above: Scouting Badges.

Above: Scouting Badges.

As far as historical context goes, the new museum’s items are in excellent company. You can hardly throw a rock in this part of the state without hitting something of historical interest: swales of the Santa Fe Trail still visible in the grasslands, a 146-year-old inn in Cimarrón, nearby ghost towns, historic cemeteries, era-shaping epics like the Colfax County War, dramatis personae like land baron Lucien Maxwell and mountain man Kit Carson—all converge here, like mighty rivers joining their waters across time. And just like rivers, the history here had the power to shape the land and alter the story that played out across it.

So, too, did Oklahoma oilman Waite Phillips, the man to whom Philmont owes both its existence and its portmanteau (“Phil” from Phillips, “mont” from the Spanish word for mountain)—although he would probably have rejected outright any such suggestion. Indeed, Waite was so modest that, when someone hung a new portrait of him and his wife on the wall of his beautiful Villa Philmonté summer ranch, which he had built south of Cimarrón, he insisted it be taken down and put in a closet somewhere out of view, lest visitors think he was presenting himself as lord of the manor. You can tour Villa Philmonté today and see that very portrait, still hanging in a downstairs closet as requested. (His main house, in Tulsa, Oklahoma, is the heralded Philbrook Museum of Art.)

Waite built Villa Philmonté between 1926 and 1927, and in 1938 he donated it, along with 36,000 acres of land around it, to the Boy Scouts of America, a generous gift that he later outdid with another 91,000 acres and additional properties in Oklahoma that would provide a source of revenue to keep it all going. Several decades and a few more land acquisitions later, that place is now the 140,000-acre Philmont Scout Ranch.

“The only things we keep permanently,” Phillips once wrote, “are those we give away.”

Read more: Life, Death, and Community in Corrales.

BACK IN THE SUMMER OF 1981, a young Scout named Dave Werhane came to Philmont from his family’s farm in northern Illinois, eager for adventure. So taken was he by his experience that he returned in 1983. And again the next year, this time as a summer staffer in the dining hall. Only 17 years old, he had to arrive before the end of the school year, so his teachers sent the paperwork for his junior-year finals. Dave completed the tests in the original Philmont Museum, under a watchful staff member’s eye. In 2012, now an adult, Dave returned again, this time to run that very museum, as well as the other three museums on Philmont’s property. As director, it falls to Dave to help oversee the construction and management of the National Scouting Museum. To him, Philmont is still an adventure.

“We have everything from dinosaurs to astronauts,” he says with enthusiasm.

Dave is the right person in the right position at the right time. He’s intensely practical, nice, and always striving to do the right thing. He’s like a living Scout Handbook. He moves effortlessly from phone calls with donors to figuring out how to disassemble a mud wagon so it can be brought into the new gallery to detailed conversations about the width of plywood at weekly construction meetings. When my pen ran out of ink taking notes, he produced both a pen and a pencil and reminded me again of the Scout motto. He uses an old pickax handle as a doorstop. At times he’s so moved when recounting a story of the Scouts—like the effort they led to sell war bonds during World War I —that he tears up. In lieu of payment for the meals I eat at the Philmont dining hall during my visit, he asks that I instead thank the cafeteria staff for their hard work.

We sit together in the temporary museum building, where the displays and gift shop items from the old museum await the opening of the new one, and Dave tells me a story. He was at an airport recently, wearing a belt buckle with the Philmont Scout Ranch logo and name. That caught the attention of another traveler, who was soon sharing with Dave his own fond memories as a Scout at Philmont many years ago. “You can’t wear anything that says ‘Philmont’ and go to a public place and not be stopped,” Dave says.

Above: Daisy Allen curares these and other gems at the new National Scouting Museum, which is overseen by Director Dave Werhane, a former Scout.

Above: Daisy Allen curares these and other gems at the new National Scouting Museum, which is overseen by Director Dave Werhane, a former Scout.

That has to do with the beauty of the place, certainly, and with the fellowship that Scouts find here, and with the lasting memories that those two things combine to create. It also has to do with the ability of Philmont to provide, as Dave succinctly puts it, “a daily lesson in viewpoints.” To date, more than a million Scouts have hiked the trails through these mountains on itineraries that lead them through a selection of 36 camps and experiential programs, learning wayfaring skills, practicing first aid, climbing rocks, running obstacle courses, participating in living history programs, practicing conservation, building an actual replica railroad, gazing at the stars, and pondering the silence. In so doing, they experience the sort of seminal moments that help them learn about themselves while simultaneously inspiring them to something bigger. In that sense, the name Philmont has a layered meaning. It’s a place, yes. But it’s also a transformation.

Read more: The Legend of La Luz Pottery.

LATE AFTERNOON, DAVE LEADS ME, along with Nancy Klein, who was the curator at the Villa Philmonté for 23 years and is now serving as outreach director for the National Scouting Museum, on a walking tour of the new building. Dave points out the areas that will become the library, the gift shop, the archives and research collection, the community meeting room, the staff offices, and the bright, open entry area that will welcome visitors. They’ve been careful to preserve or replicate the design of items from Philmont’s original museum, like the latticed ceilings and vigas, so that returning visitors will find things that feel comfortable.

In the gallery area, the heart of the building, there’s plastic on the walls and a bare cement floor, but magically the finished space takes shape around us, brought to life by the excitement in Dave’s voice. This will be the founders’ corner, he says, pointing to an area just inside the entryway, and I can see them: Lord Robert Baden-Powell; Chicago publisher William D. Boyce; Ernest Thompson Seton, who had founded the Woodcraft Indians in 1902; Daniel Carter Beard, who had founded the Sons of Daniel Boone in 1905; and Dr. James E. West, who served as the first Chief Scout Executive of the organization in 1911.

Over here, Dave points out a timeline of the Scouts—and just as quickly, there they are: mannequins with Scout uniforms showing the change in apparel over time, the cargo pants and the neckerchief and the web belt and the uniform cap. A display of every merit badge ever given, from Archery in 1911 to Farm Mechanics in 1928 to Environmental Science in 1972 to Robotics in 2011 to Exploration in 2016, and 150 others.

Not just displays do I see, but visitors, too, looking perhaps for the uniform they remember from their youth, and the smile that hits their face when the memories return. “You realize that these things have touched so many lives,” Dave had told me earlier, “and some of them deeply.”

Over here, exhibits on notable Scouts, like actor Harrison Ford and President John F. Kennedy. An area dedicated to the Order of the Arrow, an honorary society for the Scouts. Exhibits on Philmont itself, plus information on Cimarrón and the Santa Fe Trail. An old railroad box phone used by men laying tracks through New Mexico in the 19th century; money bags from the long-gone mining camp of Baldy; Native American baskets and jewelry. And in this space, Dave nods, a special exhibit on Seton, to include selections of his paintings and items from his extensive Native American art collection.

We’re joined by Doc Rand, the project superintendent with Flintco construction company, whose job for the past two years has been to oversee the operations and crew. Doc knows of the building’s historical significance and what the museum will mean to so many people. He tries to impart that to every member of his crew so that those feelings become part of the structural fabric of the place. When a new worker starts, before they even put on a hard hat, Doc has them watch a video about the museum so they understand why it matters.

“This building is going to be here forever,” he tells his workers. “Sign your name to it.”

STAY AWHILE

The Blue Dragonfly Inn, in Cimarrón, features comfortable beds and beautiful views of the western horizon, an indoor heated pool, a parlor with a fireplace, and plenty of other reasons to “take your watch off,” as owners Colin and Erin Tawney say. It has four rooms with two shared baths, plus homemade breakfast specialties like New Mexico Eggs Benedict.

The Casa del Gavilan Historic Inn, bordering Philmont Scout Ranch, was recently added to the National Register of Historic Places. Built as a Pueblo Revival–style home in 1911, the property has a subtle and distinctive beauty that echoes the natural world surrounding it, with six rooms, a tranquil courtyard, and stunning views in every direction.

Located along the Santa Fe Trail, the St. James Hotel, in Cimarrón, is 146 years old, with historic rooms (at least one of them haunted), as well as a modern annex and Lambert’s, a restaurant with some of the finest dining in northeastern New Mexico.

PHILMONT MUSEUMS

The National Scouting Museum–Philmont Scout Ranch hosts a dedication on September 15, at 11 a.m. All are welcome—former and current Scouts especially. The event is free, and parking is available.

Philmont is open only to Scouts on excursions, but visitors are welcome at any of its museums, including the National Scouting Museum, plus these three:

Villa Philmonté. The second home of Waite Phillips and his family, who owned the ranch for 14 years before deeding it to the Boy Scouts of America. Tours of this resplendent house, built in Mission and Spanish Colonial Revival styles with a strong Mediterranean influence, are often led by a Scout. Among the many highlights is the parlor’s player piano, which still has the original rolls that entertained the Phillips family.

Chase Ranch. This former ranch house, built in the mid-19th century and remaining in the Chase family for the next century and a half, offers a glimpse of ranch life in northeastern New Mexico from the 1800s to the present. Visitors can see historic interiors, an orchard, a tack room, and even a small family cemetery.

Kit Carson Museum at Rayado. The former mountain man and army officer’s house sits along the Santa Fe Trail in the small community of Rayado, about 11 miles south of Cimarrón on NM 21. Living history reenactors provide a glimpse at how the 19th-century compound served as a house, hotel, service station, community hall, trading post, church, and fort.