Above: Jake Skeets at El Rancho Hotel in Gallup, near his hometown on the Navajo Nation. Photographs by Gabriella Marks.

ONE DAY IN 2011, Jake Skeets leaned on the wall outside the Frontier Restaurant, on Albuquerque’s Central Avenue. The University of New Mexico undergrad was hungry in two ways: for lunch and for poetry.

In his hands he held one kind of sustenance: a book by Joy Harjo. The future poet laureate of the United States had just signed it for him after giving a reading across the street, and Skeets was buzzing from his brush with one of the boldface names of Native American literature. As he read her words, Harjo herself walked up. Recognizing her book, and perhaps Skeets’s boundless appetite for writing, she invited him inside to chat.

“She bought me lunch here,” Skeets remembers on a late-summer afternoon less than a decade later, the corners of his mouth quirking up at the memory. Earlier, he had texted me where to meet: “I’m at Frontier now in the last back room with the Navajo rugs (seems fitting lol).”

Surrounded by the earth-toned weavings, our booth nudges up to an oil painting of John Wayne, who wields his army revolver at me over Skeets’s left shoulder. The poetic juxtapositions are almost too on the nose. After all, the Duke is one of “A List of Celebrities Who’ve Stayed at the El Rancho Hotel.” That ghostly poem (reprinted below), from Skeets’s debut collection, is about the historic base for movie productions in Gallup, near where Skeets grew up, in Vanderwagen, on the Navajo Nation.

A plate of chips and guacamole sits before him, but the poet is too excited to eat. Tonight he will give the first official reading from that book, Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers, which was selected as a winner of the 2018 National Poetry Series. Sitting at his old stomping grounds on the eve of his book’s publication, Skeets traces his journey back to something Harjo said to him just a few tables away.

“I asked her, ‘How did you do this? How did you navigate becoming a writer?’ And she said, ‘Study others and see what they did, and see if it works for you.’”

Skeets followed her advice, becoming the latest in a string of nationally acclaimed poets who, like Harjo, attended the Institute of American Indian Arts, in Santa Fe. After he graduated from UNM in 2014, Skeets pursued an MFA degree at IAIA’s Low Residency program (affectionately dubbed “Low Rez,” a riff on the word reservation, with all its connotations). Though the MFA program is in only its eighth year, it has joined the institute’s undergraduate creative writing department as a notable incubator of the new poetic vanguard.

Above: Arthur Sze, poet, professor, and 2019 National Book Award winner.

Above: Arthur Sze, poet, professor, and 2019 National Book Award winner.

This latest generation of IAIA poets is, as Harjo wrote of her own community 25 years ago, “the stars who were created by words.” On the page and the stage, their lines snarl, slam, and sing. They push English all around the margins, filter it through their Native tongues, run couplets and stanzas into a cycle of freewheeling experimentation until wholly new forms emerge. Their issues are often cultural—they speak of spoiled landscapes, rotten treaties, appropriation and restitution, and down-low queer love on the rez—but their craft goes toe-to-toe with writers of every background. Their words project both melancholy and resilience, spinning beauty from pain and everyday life. Over the past decade, their voices have risen to a roar, leading, last June, to Harjo’s becoming the first Native poet to take up the mantle of the nation’s laureate. They are artists of a proud and self-aware indigeneity, and their work demands attention.

“I arrange my father’s boarding school soap bones on white space / and call it a poem,” Skeets writes.

“Now / make room in the mouth / for grassesgrassesgrasses,” Layli Long Soldier tells us.

In Orlando White’s “Finis,” “A sound-loop hangs from the white gallows of the page.”

Two years ago, media outlets ranging from BuzzFeed to The Paris Review named IAIA the epicenter of a “new Native renaissance” in literature. (The first so-called Native renaissance, from the late 1960s to the 1990s, included writers N. Scott Momaday, Leslie Marmon Silko, Louise Erdrich, Harjo, and Sherman Alexie.) Besides Skeets, the graduate program at IAIA has since turned out Tommy Orange (Cheyenne/Arapaho), whose first novel, There There, was a finalist for the 2018 Pulitzer Prize. That same year, fellow MFA and First Nations memoirist Terese Marie Mailhot’s debut, the New York Times bestseller Heart Berries, was named one of Time magazine’s best nonfiction books. In the introduction to the 2018 anthology New Poets of Native Nations, editor Heid E. Erdrich writes that “increased access to education and mentorship experiences, particularly through the Institute of American Indian Arts, are no doubt some of the reasons publication has opened up for poets of Native nations.”

“The list of poets who have gone through IAIA is so long,” Skeets says. “I knew that was the place where I wanted to go.”

Read more: Albuquerque’s new poet laureate champions the area’s cottonwood forest.

THESE POETIC FIREBRANDS WERE catalyzed in part by the influence of a non-Native writer, Chinese American poet and professor emeritus Arthur Sze, who won a National Book Award this fall for his most recent collection, Sight Lines. He began teaching in the creative writing associate’s program at IAIA in 1984. “In the eighties,” Sze remembers, “Native poetry was very conventional, unfortunately—stereotypical even, with the sunset or horse or landscape, very traditional. And by 20 years later, these young poets were writing in all sorts of different directions.”

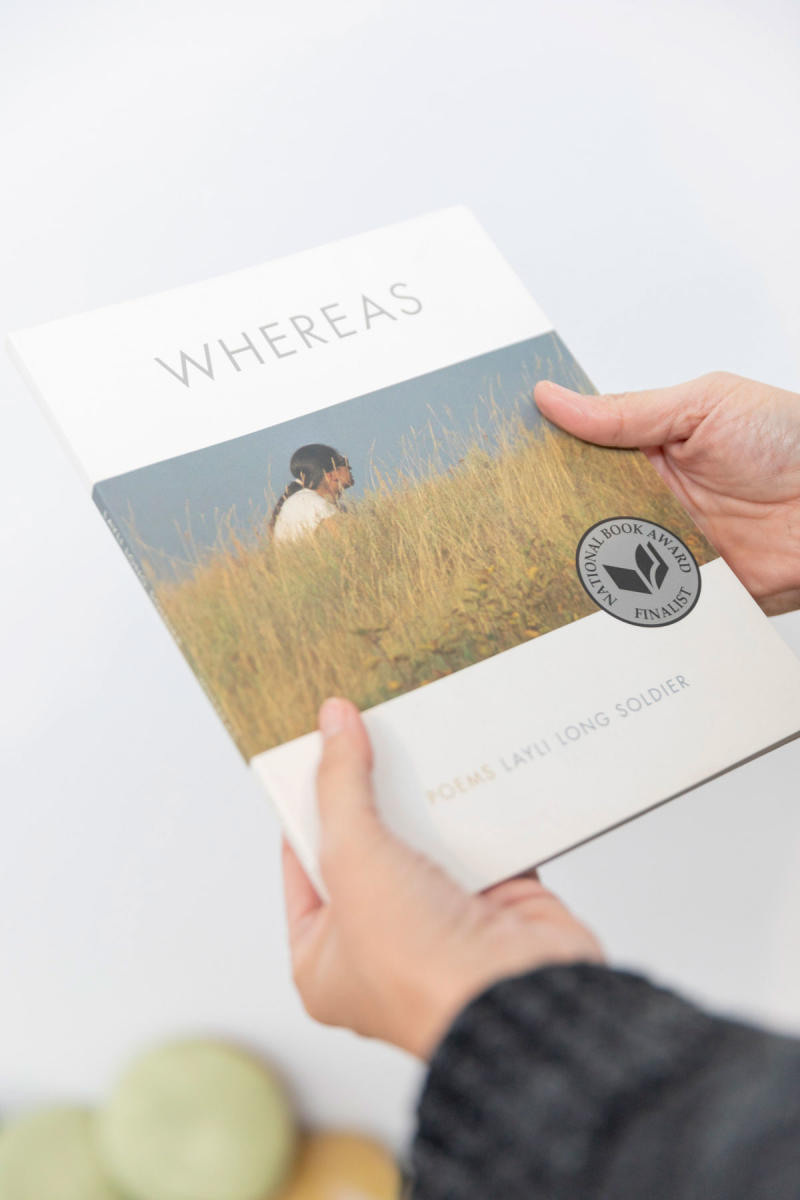

Above: Long Soldier's WHEREAS won the National Book Critics Circle Award.

Sze describes a checkered chronology for the department, which stabilized—along with the institute as a whole—only after Congress pulled IAIA out from under the administration of the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the late 1980s, more than 25 years after the school was first established with funding from the BIA. Sze hired more Native faculty, secured grants for a revolving cast of writers in residence, and worked with graduate institutions and writers’ conferences to award scholarships to promising undergrads. In 2000, a 140-acre campus was dedicated on the southern outskirts of Santa Fe; after years of offering only associate degrees, it awarded its first bachelor’s degree in creative writing in 2003.

A cohort of well-known alumni have returned at various points to teach in either the undergrad or MFA program. Oglala Lakota poet Layli Long Soldier (2009), whose 2017 collection WHEREAS won the National Book Critics Circle Award and was a finalist for the National Book Award, teaches BFA poetry classes. Long Soldier’s poet forebears in the program include fellow Whiting Award recipients James Thomas Stevens (Mohawk, 1991) and Sherwin Bitsui (Navajo, 1999), as well as Orlando White (Diné, 2006) and Santee Frazier (Cherokee, 2006), who have been honored with Lannan Foundation grants.

For the 2019–20 academic year, 28 students have enrolled in the undergraduate creative writing program; about a quarter specialize in poetry. Seventy-one percent of those students identify as Native. Of the 46 MFA candidates, around a third concentrate on poetry, and 54 percent are Native. As for the MFA faculty, “we have always been the pocket of the program that has been completely Native,” program director Frazier says proudly.

Frazier theorizes that more than one generation of IAIA graduates may be able to trace the ability to construct potent word pictures to an unlikely source: ancient Chinese and Japanese poetry. “Arthur taught this amazing class called ‘The Poetic Image,’” Frazier remembers of his undergrad days. Sze explains, “I would put up a poem on the whiteboard by, say, Li Bai, a Tang dynasty poet, and I would show the students three different translations in English and walk them through it, character by character, word by word. I would have them make their own translations into English. They would make translations into their own Native languages, and they would write poems inspired by the poems they saw.”

Above: Jake Skeet's book features a photo of his uncle Benson James, taken by Richard Avedon.

Above: Jake Skeet's book features a photo of his uncle Benson James, taken by Richard Avedon.

“I think that’s something that we see in a lot of IAIA graduates, at least in the poetry realm, is this attention to image,” Frazier says. In his poem “Bluetop,” he describes an indelible predawn journey in which sound merges with light:

The radio

fades in and out of static,

tractors revving, cows lowing,

and we may never make it back,

home still five hills away, daylight

coming over rocky edges of the hills.

Sze and other formative instructors forged a legacy of pushing the boundaries of language. “They could use Native vocabulary, they could use Native syntax, they could use Native time and space, they could sort of push the English in new ways,” Sze remembers. “I think that’s part of the strand of what’s emerging in this new generation.”

That spirit of linguistic innovation has become a hallmark of IAIA poetry. “I have this theory that because of where IAIA is located—it’s in the middle of nowhere—that’s where those breaks come from, those big, long white spaces,” Skeets says at the Frontier, referring to the spatially diverse poems of White and Long Soldier.

“When you look at how experimental many of our alumni are, that definitely is something that shaped me, that I pass on as the next generation working with IAIA students,” Stevens tells me the day after I sit in on his Poetry Writing I workshop. In class, I watched as he repeated familiar writing instructions: “Read your own work aloud” and “Show, don’t tell.” But he also encouraged students to experiment with synesthesia—to mix and mismatch their senses.

“There’s a different way of writing, a Native way that is not derivative,” he says. “Publishers are finally giving credit to how different the worldview is, and how that comes out in the work. Whether it’s Sherwin Bitsui’s Flood Song—you know, just this giant flood of imagery coming at you the way that the Western world comes at the Native community—or Orlando White’s look at the English alphabet [in his 2015 collection LETTERRS] and what that’s like, to just be handed that alphabet and somebody says, ‘Here, learn it,’” a reference to the enforcement of speaking English over Native languages.

Read more: Meet the five Native fashion designers pushing Native couture to new heights.

The idea of student-centered learning, where the professor is not the focal point of the classroom but instead serves as a more intimate writing mentor, is a thread that stretches from the undergraduate level to the MFA program. Graduate students begin their two-year degrees on campus over the course of a week in July, during which students and one faculty member participate in a workshop, verbally evaluating a packet of student poems that they have had a month to read and absorb. Between the summer and early January residencies, students read books, submit critical essays, and engage in long-distance learning with one chosen mentor, who is assigned between one and four students per term.

“I think being able to work with a mentor, an established writer, one-on-one for an entire semester is definitely an advantage compared to working with professors who are teaching several classes or who have several students at a time,” Frazier says. After two years, students submit a thesis of work created during the program, which they present at a public reading, explain in a craft talk, and defend in a public forum. The “low-rez” aspect means that the school attracts more diverse students, including working parents, writers in remote locations, and those who are heavily involved in their home communities. They stay in touch with their mentors on a semi-weekly basis via email, Skype, or telephone. “By the end of it,” Frazier explains, “they should be leading the mentor just in terms of what they need from their interactions with them.”

ON A WEDNESDAY afternoon during the fall semester at IAIA, neon-yellow shocks of chamisa along the campus pathways are set off by the looming shadows of the Sangre de Cristos. The striking setting feels ripe with creative potential. Inside the Center for Lifelong Education building, Layli Long Soldier instructs her Poetry Writing IV class to remember that they aren’t just writers, they are visual artists. “You’re working beyond the page,” she says.

Above: Layli Long Soldier and James Thomas Stevens nurture new poets at IAIA.

Above: Layli Long Soldier and James Thomas Stevens nurture new poets at IAIA.

Long Soldier is lecturing on documentary poetics, in which documents not produced by the poet are partially deleted, rearranged, or otherwise manipulated to create new meanings. It’s what Long Soldier did in WHEREAS, a book written as a direct response to a 2009 congressional apology to Native Americans. In “38,” she writes:

One trader named Andrew Myrick is famous for his refusal to provide credit to Dakota people by saying, “If they are hungry, let them eat grass.”

There are variations of Myrick’s words, but they are all something to that effect.

When settlers and traders were killed during the Sioux Uprising, one of the first to be executed by the Dakota was Andrew Myrick.

When Myrick’s body was found, his mouth was stuffed with grass. I am inclined to call this act by the Dakota warriors a poem.

She gleefully draws a giant diagram of a sample documentary poem on her whiteboard. With its cross-out squiggles, black boxes, and ample blank spaces, it resembles an Abstract Expressionist painting.

After class, student Serena Rodriguez praises the diverse and contemporary focus of the writing program. “I’m pretty sure I haven’t studied one white cisgender male since I’ve been in this school, and it is so refreshing. The professors here go out of their way to choose these poets specifically. It all has this bigger meaning, whether it be in the way it’s written on the page or what the person is trying to say. I mean, it goes beyond the Romantics. There’s so much sustenance in what we’re studying.”

“When we see our contemporaries delving into poetry, it gives us encouragement, a pathway to use the English language in new and fun ways,” says student Jesse Short Bull. “Through IAIA, we’ve discovered the first wave of poets, and we’ve kind of gone through the second wave. I’m not sure where a lot of my classmates and I fall, but we’re in that next wave. And it’s pretty exciting.”

In the hall outside Long Soldier’s class, I overhear a more abstract conversation. “I have a language question regarding a dream,” senior Teklu Hogan calls out to Stevens, his former Poetry I instructor. “I need to know, does this mean anything to you? ‘La chez de la suisse.’”

Stevens repeats the phrase. “Sounds like ‘the house of the Swiss person,’” he muses. Hogan nods wonderingly. He seems mostly unfamiliar with the French language. “I had a dream with an Alaska Native word in it,” Stevens offers. “I asked my class the next day, what is apa? And they’re like, ‘Oh, it’s grandfather.’”

The exchange feels surreal, like I’ve stumbled into a communal dreamworld where more than one intuitive language is spoken. For Skeets, who now teaches poetry at Diné College, that describes the shared indigenous ethos at IAIA. “I think we’re a lot more open with each other, so that helps the workshop itself,” he mused at the Frontier. “Because it’s so centered in identity, I was able to not worry about having to explain my content, as far as where I come from.”

Above: Award-winning poet Santee Frazier leads IAIA's MFA program in creative writing.

Above: Award-winning poet Santee Frazier leads IAIA's MFA program in creative writing.

Short Bull compares the exchange of ideas at IAIA to the shorthand spoken by a large family, albeit one with many branches. “Here we have many different nations, many different people. But we think the same way, we even talk the same way, we laugh the same way.”

It’s clear, however, that the poets at IAIA do not exist in a vacuum, or even an echo chamber. Says Rodriguez: “When it comes down to the fruit of the writing that comes out of IAIA, I really feel like there’s a lot of voice here. There’s something to be said, that needs to be said and needs to be heard.” She looks down the empty hallway, then over at Hogan, still mulling over the meaning of his dream. “There’s a reason why this writing program is getting noticed.”

LISTEN UP

The IAIA Low Residency MFA in Creative Writing Program presents the Winter Readers Gathering on its campus in Santa Fe daily, January 4–11 (except January 8). Featured authors read at 6 p.m. All readings are free. For details, see iaia.edu/happenings.

READ ALONG

Writer Molly Boyle recommends these recent books by Native poets.

- New Poets of Native Nations, edited by Heid E. Erdrich (Graywolf Press, 2018)

- Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers, by Jake Skeets (Milkweed Editions, 2019)

- An American Sunrise: Poems, by Joy Harjo (W.W. Norton & Company, 2019)

- Aurum: Poems, by Santee Frazier (University of Arizona Press, 2019)

- WHEREAS, by Layli Long Soldier (Graywolf Press, 2017)

HOW TO READ A POEM

When I’m teaching students at Diné College, they often don’t have experience with reading poetry. I always try to start with the poem itself, not worrying about message or meaning. For me, poetry is meant for playing with language. We start there first, and then we can work toward or try to find meaning.

You’re not meant to understand poetry, you’re meant to experience it. That’s why I go through these steps with my students.

Sound: The first thing I have them do is just read the poem and listen for the sounds that they might hear. Are there words that are being used that are creating interesting sounds when in your head versus when you read them out loud?

The words on the page: See how things are spaced, see if lines are connected together in stanzas. How is it arranged, how is the poet playing with the white space and the text?

Image: What do you see when you read the poem? Are there certain images that remain in your mind as you’re reading? Do they remind you of things in your own life?

Message: What is its tone, storyline, speaker? What is the poet doing by incorporating all these elements? What are the techniques that they’re using in terms of line or rhyme? How do these all add up to what they’re trying to say? Poems can sort of shape themselves in a variety of different ways. There’s no such thing as permanence for a poem, I think. Yes, it’s published, but that doesn’t mean it’s a permanent thing. The poem itself will always be changing and transforming, depending on who the reader is.

If you actually go into the El Rancho Hotel, in Gallup, if you go to the second floor, they’ll have these different photographs, some of them autographed, of celebrities who’ve visited. That’s what inspired that listing. But then as you’re walking around this lobby, you can hear the train pass in the background because the hotel is right across from the train tracks. So you can definitely hear what’s going on outside, and what’s going on outside are a lot of darker things. So there’s kind of this weird moment where there are dual realities, where we have this romanticized notion of what Gallup is and then we have the starker reality of what’s going on outside by the train tracks. —Jake Skeets

A List of Celebrities Who’ve Stayed at the El Rancho Hotel

- Doris Day

The carpet grabbed her shoe. Her pearls snowflaked its deep red

- Humphrey Bogart

He sat under a framed elk head with a cigar.

The man sits with a cigar under Bogart’s framed head.

- Jane Fonda

She left her room in a scurry. A ghost sat down on her bed. It was all the words

ever spoken, however, that dropped a finger on her cheek.

- Katharine Hepburn

She never left her room. She was busy looking at the leaves

on the trees

shimmer like apostrophes.

- Ronald Reagan

The president shook hands with a photographer that shook hands with my uncle

Before my uncle was killed a few blocks up from the hotel.

- Jean Harlow

She was stunned to see dark figures across the train tracks train tracks train tracks train tracks.

From Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers, by Jake Skeets (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2019); reprinted with permission.