ERIN CURRIER STANDS astride a world of garbage—wrappers, posters, magazines, bits of paper people have forgotten or discarded—and in it sees truth and beauty.

A Currier painting is born from a few simple ingredients. Start with a sketch, a wooden panel, some primer, tubes of paint. Add cans of glaze, wax, and sealant for finishing. And, of course, you’ll need bags of neatly folded, sorted, and wrapped garbage. This last part is very important. You’ll find this detritus of everyday life as you hop from continent to continent. You can take it back in your luggage or ship it directly. With this, you can pack gut-level truths between layers of forgotten objects.

With her 2016 shows, Rogues and Reinas, at Blue Rain Gallery in Santa Fe, and Songs of the West, at the Harwood Art Center in Albuquerque, Currier brought her punchy, prismatic style to bear on her adopted home state of New Mexico, a place she always feels imbued with surprise and magic.

“If you look closely, there’s all these clues,” she says, running a finger across the ticket stubs, immigration paperwork, and fireworks packaging she’s embedded in a recent work. The trash, which melts into the basic outlines and shapes of her paintings, helps tell the story. Take, for instance, her portrait of Johnny Tapia, Albuquerque’s ferocious boxing champ, a man whose personal story—his mother brutally murdered, his career filled with highs, lows, comebacks, and, ultimately, a tragic death in 2012—feels ripped straight from Greek mythology. There’s a universality to the story of a relentless warrior facing down long odds, and Currier plasters her canvas with its symbols: Muay Thai martial arts posters from Thailand, the tattered pages of Argentine boxing magazines, a Mexican lotería card of El Valiente (the Hero), posters from Hong Kong kung fu movies, and a samurai film festival in Japan. The garbage itself has been shipped from all over the world back to New Mexico. It comes wrapped in a cloth parcel on a slow boat from India or by airmail from Uruguay. Unlike precious souvenirs, trash never gets pilfered by sticky-fingered customs officials.

She gazes at Tapia, his chest emblazoned with a tattoo of his personal slogan: MI VIDA LOCA. “Even though he belongs to Albuquerque, New Mexico, he belongs to the world,” she says.

AT AGE FOUR, Currier received a gift that, unfolded before her, revealed her future in its crinkled lines. It was a world map. On it, she could see the little sliver of her home state, New Hampshire, but also the vastness beyond it. As a child, she visited her grandmother in Arizona. She was transfixed as she passed into the alien world of the Southwest. This young, raw landscape and the new kinds of people who lived in it made deep impressions on her, like lines in a map that can’t be flattened out. At 18, she crammed her paints and her boyfriend’s drum kit into her VW convertible and headed to New Mexico. It was a place both foreign and domestic, a place where art is embedded in the soil, pregnant with history and culture. She used the state as an inspiration and launchpad.

“I couldn’t wait to see the world,” she says. And see it she has. Stints on every inhabited continent have led her down rabbit holes, along winding roads to meet subjects she could not have imagined. “The more I travel, the more I’ve been struck by how the same we are,” she says.

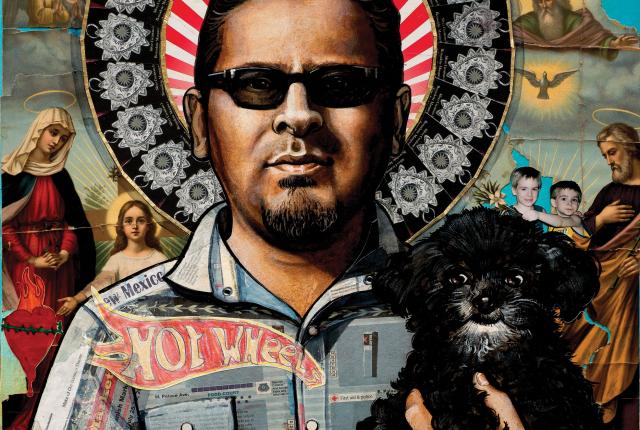

Currier’s subjects smile at you, their hands hold totems and symbols. Their cherubic faces, all circles and warm hues, invite you into the dense, richly textured world of everyday transcendence. Her recent paintings of fellow New Mexico artists, like Nicholas Herrera, El Rito’s playful contemporary santero and self-proclaimed “cool vato,” embody the heartfelt meanings that keep the globe-trotting Currier coming back to the high desert. In her portrait of Herrera, his bearish face beams and his craftsman’s hands hold a massive heart—one of his favorite motifs.

“I’ve been a big fan of his for years,” she gushes. “He puts so much heart into his work. Everything he carves, everything he puts his hands to.”

She paints the women of New Mexico as quiet superheroes, pseudo-propagandized sisters to the Tibetan and Brazilian and Egyptian women she’s painted in the past. Each year she paints fiesta queens and Miss Navajo Nation. She highlights the faces of non-white Harvey Girls—the ones who don’t look like Judy Garland. Her portrait of Ohkay Owingeh artist Gerónima Cruz Montoya shows the painter and teacher as a girl, brushes clutched in hand, whose gaze pierces the viewer. She hopes that her subjects engage the onlooker, and that they find a connection to them.

Some art is meant to be hung, arranged, and admired. New Mexican art, says Currier, serves a practical purpose. Traditional Hispanic and Native art forms are not just objects to be admired, they are pots meant to carry water, altarpieces to facilitate prayer. Currier, global garbage hunter extraordinaire, feels kinship with bulto sculptors who recycle old, discarded pieces of wood and with Native potters who wrest their medium from the very earth itself.

“New Mexico art means something,” she says, “and its meaning can be appreciated universally, because it comes from the heart."