GEORGIA O’KEEFFE’S legacy in the Southwest extends to the artist herself having become a symbol for the landscapes she painted: striking, creatively inspiring, and free. In fact, O’Keeffe’s name is so synonymous with the stunning vistas of northern New Mexico that Abiquiú has been unofficially designated as “O’Keeffe Country” by tourism promoters over the years.

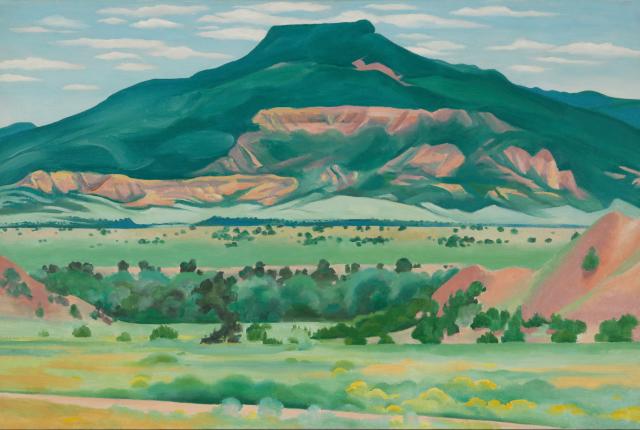

Río Arriba County’s famous mesa, Cerro Pedernal, which the artist could see from her historic home at Ghost Ranch, is recognizable to those familiar with her landscapes. Her obsession with painting it led to O’Keeffe, late in life, famously proclaiming it to be her “private mountain”: “God told me if I painted it enough, I could have it,” she said.

But Cerro Pedernal—rising as a majestic but unassuming presence on the desert terrain—goes by another name. For those who live at the six regional pueblos—Nambé, Pojoaque, San Ildefonso, Ohkay Owingeh, Santa Clara, and Tesuque—that called this land home long before the artist did, its ancestral Tewa name is Tsí Pín, and the name for the land itself is Tewa Nangeh, or Tewa Country.

“The translation is like a flint or flaking stone mountain,” says artist Jason Garcia (Kha’p’o Owingeh/Santa Clara) of Tsí Pín. Garcia is one of 12 artists participating in the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum’s exhibition Tewa Nangeh/Tewa Country, which runs through September 7, 2026.

The show features newly commissioned works by Joseph “Woody” Aguilar (San Ildefonso), Samuel Villarreal Catanach (P’osuwaegeh Owingeh/Pueblo of Pojoaque), John Garcia Sr. (Kha’p’o Owingeh/Santa Clara), Charine Pilar Gonzales (San Ildefonso), Marita Swazo Hinds (Tesuque), Matthew Martinez (Ohkay Owingeh), Arlo Namingha (Ohkay Owingeh/Hopi), Michael Namingha (Ohkay Owingeh/Hopi), Eliza Naranjo Morse (Kha’p’o Owingeh/Santa Clara), Martha Romero (Nambé), and Randolph Silva (Kha’p’o Owingeh/Santa Clara).

In it, these artists wrest away a narrative of New Mexico’s “discovery” by Anglo artists in the early 20th century. Placing Tewa Nangeh/Tewa Country inside the museum that bears O’Keeffe’s name suggests the institution is more than open to an exchange that eschews hagiography—and the exhibition places her off-center by showing her work only in relation to that of the Native artists.

Jason Garcia is known for his Tewa Tales of Suspense! print series, which examines cultural clashes between Anglo and Hispanic settlers and Indigenous populations—foremost among them the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, which he presents as mock comic book covers. A print from the series, included in the exhibition, brings the storytelling into the 20th century. It shows a rendering of O’Keeffe in her iconic black dress and hat, Tsí Pín in the background, standing before a sign that used to read “Welcome to O’Keeffe Country”—before the word “Tewa” was spray-painted over her name.

“I think our theme started with O’Keeffe’s quote regarding Tsí Pín as her own private mountain,” says Garcia, who co-curated the exhibition with Bess Murphy, the museum’s Luce Curator of Art and Social Practice. “A lot of it was asking the collaborators, ‘How do you respond to this particular quote?’ and expanding on that.”

To outdo O’Keeffe’s prodigious treatment of the landmark, Garcia is creating a series of his own landscapes that also take Tsí Pín as its subject. As the exhibition progresses, Garcia will add to the evolving wall of works on paper in which he’s captured the mesa in mixed media, acrylics, and alcohol marker. “O’Keeffe is said to have painted Tsí Pín 29 times, so the goal is to paint it 30-plus and reclaim ownership of the mountain,” he says.

To understand the reclamation’s importance, it’s crucial to consider that when O’Keeffe made New Mexico her permanent home in 1949, she wasn’t settling on unoccupied land. The six Tewa-speaking pueblos maintain their dances, ceremonies, language, and connections to ancestral villages. And that language, including the Tewa place names to which most visitors are unaccustomed, is given to locations and people referenced in the show. The exhibition’s naming process is the result of collaborative efforts between artists and researchers, including archaeologist Joseph “Woody” Aguilar, who is also San Ildefonso Pueblo’s deputy tribal historic preservation officer, and educator Matthew Martinez, who served as first lieutenant governor of Ohkay Owingeh.

“Selecting a group of artists who are deeply invested in telling the story of place was pretty critical,” Murphy says. “I think we did wind up with—and there was some intention behind this—working with a group who do a lot of research-based work in their practice, where they are looking into different historical events, different periods, and individuals, whether it’s video and film or abstract sculptural work, or immersive installations.”

Language is an indelible part of the meaning of a place, and the collaborators created a map for the exhibition that details Tewa place names in lieu of the names christened by settlers. The boundaries of Tewa Country show Kúu Séng Pín (the Sangre de Cristos) to the east, Okuu Pín (the Sandías) to the south, Tsikumu Pín (Chicoma Mountains) to the west, and T’say Shun Pín (San Antonio Mountain) to the north.

But the idea of reclamation doesn’t just apply to the landscape where, among O’Keeffe’s scattered ashes, Indigenous communities continue to live and thrive. The assertion that this land is Native land—and that the museum itself occupies that land—is emphatic in the installation by Eliza Naranjo Morse. Her work in progress is a large-scale landscape painting with an earthen path leading from it or to it, depending on one’s perspective. “It’s extending the landscape of the mural into the physical space of the exhibition,” Murphy says.

The clay, earth, and natural pigments used to create the mural and path were hand-gathered, a way for Naranjo Morse to reconnect with her heritage and community, which maintains an outstanding pottery tradition.

Tewa Nangeh/Tewa Country also features O’Keeffe works that are meant to inspire dialogue with those by Tewa artists. Items from the artist’s personal collection, including paintings and ephemera from her home and studio, were also selected by the participants to display. “The O’Keeffe paintings don’t have extensive labels intentionally,” Murphy says of the exhibition’s design. “We really wanted to center the artists’ voices in this project, so all of the text, the audio tour stops—everything is in their voices, and their voices alone.”

Artist Michael Namingha’s Disaster 8, from his silk-screened Disaster series, depicts a pyrocumulonimbus cloud that occurred during the 2022 Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon wildfire, the largest in New Mexico’s history. Its golden hues and amorphous central image recall O’Keeffe’s Pelvis Series, Red with Yellow (1945), in which the imagery—a yellow sky seen through the hole of a pelvic bone—is abstracted. Formal qualities of Namingha’s work, such as its color and the curving sweep of the central toxic cloud, share visual affinities with O’Keeffe’s painting.

While Tewa Nangeh/Tewa Country is not an exhibition where each Indigenous work directly contrasts with similar work by O’Keeffe, some pairings reveal the “mother of American modernism,” as O’Keeffe is known, to be a continuing source of artistic inspiration. At Ghost Ranch, for instance, Marita Swazo Hinds discovered O’Keeffe’s trove of teapots. Her work Let’s Have Tea, Tea Time With Georgia imagines a conversation with the artist while Hinds creates a teapot of her own from regional micaceous clay.

The artists’ testaments, filmed by 2024 Sundance Native Lab fellow Charine Pilar Gonzales, are also screened, along with Gonzales’s short film This Land Carries Us, which covers Tewa land and people through the voices of her relatives.

As some of O’Keeffe’s works with animal bones might suggest, we are all just blips on the cosmic landscape, here for a time and then gone. But as Tewa Nangeh/Tewa Country attests, if one iconic figure—an individual—can loom large nearly 40 years after her death, then what can linger of the people who have created art in that place for millennia? When they’re grounded in the realities of Pueblo life, where efforts to preserve and maintain lifeways continue

to endure, some myths of ownership require this careful of a reexamination.

Michael Abatemarco has written extensively on both Pueblo art and culture and on Georgia O’Keeffe’s life and work.

Tewa Nangeh/Tewa Country

Through September 7, 2026; Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, 217 Johnson St.; 505-946-1000, okeeffemuseum.org

Michael Namingha’s Abiquiu #3. Courtesy of Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

A FLOWERING INSTITUTION

The expanding Georgia O’Keeffe Museum is taking cues from its surroundings.

The expanding location of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum campus off Grant Avenue in downtown Santa Fe, slated to open in 2028, got a geography lesson after contractors began arriving each morning at the dig site for the new building’s foundation to the mystery of standing water. As it turns out, according to Devendra Contractor of DNCA Architects, an oxbow from the Santa Fe River once crossed this land. Water from underground waterways, spreading horizontally from the geological Tesuque Formation through fissures in the bedrock, was leaching in through the walls of the pit.

The new structure—which is in the process of being waterproofed and shored up with concrete from the inside—will add a 54,000-square-foot building to the museum campus for showing and preserving more of its collection. The plans include 16,000 square feet of gallery space, 22,000 square feet for collection storage with a state-of-the-art conservation lab, a learning and engagement center, and a community garden and gathering space with a route connecting Sheridan and Grant avenues.

Unlike many of the surrounding structures, whose Pueblo Revival architecture gives the appearance of adobe construction though they are often made of concrete and brick, the new museum will be made from adobe bricks created from the excavated soil at the construction site.

“This building is about authenticity as it’s related to materiality,” Contractor says. “It’s not about style. We look at how the past influences the present, but also how all the things around us impact the field. Here, this notion of Santa Fe Style will be through an authenticity that redefines what that is.”