AS YOU HEAD EAST OUT OF SANTA FE, veering north toward Las Vegas and then beyond, the mountains flatten out into vast high plains below a sweeping sky. In 140 miles, the unassuming town of Roy appears, encompassing about two square miles and just over 200 people. A few businesses mark its quiet streets, and the most common footwear is cowboy boots. But on any given weekend, an unexpected group of tourists drops in, so many that they sometimes double the area’s population: rock climbers seeking the thrill of new challenges in bouldering.

“The climbing opportunities there make the region one of the top outdoor recreation destinations in the state—even in the country,” says Axie Navas, director of New Mexico’s Outdoor Recreation Division.

Just looking at the pastoral grasslands, you might not believe her. But about 20 miles out of town, those plains give way to a wide, rugged system of canyons carved by the Canadian River. The waterway meanders nearly 1,000 feet below its canyon rim, and stacks of sandstone cliffs punctuate the slopes. The climbing here doesn’t happen on sheer walls, however; it’s the boulders that have earned this unlikely spot a stellar reputation.

The high plains reach to the sky.

The high plains reach to the sky.

“The first time you go to Roy, it’s pretty shocking,” says William Penner, an Albuquerque climber who began exploring the area in 2000. “You’re like, Huh, this is weird. It’s plains and plains and plains, and then it’s totally different.”

On his way home from a work trip to a distant ranch, Penner, an archaeologist, was driving through the remote region when something caught his eye. “I looked at a particular boulder right along the highway there,” he says. “The rock was amazing. I had never heard of anyone climbing in that area and was just blown away by the possibility.”

Bouldering is a type of climbing that involves scaling shorter routes, typically on freestanding boulders. In recent decades, it moved from the fringes of the climbing world into a popular discipline within the rapidly growing sport.

Above: Matthew Stephens tackles Slug, a “problem” in the Jumbles area of Mesteño Canyon, part of the Kiowa National Grassland.

In some ways, bouldering is the simplest way to climb. It doesn’t call for the same safety equipment (ropes, harnesses) and techniques (anchor building, belaying, rappelling) used in traditional and sport climbing. Boulderers simply pack in crash pads—large cushions that they set up below the “problem,” or climb, that they’re working on—and spot each other. It’s just them, the rock, and their climbing shoes. The land surrounding Roy, it turns out, boasts exceptional, accessible sandstone boulders.

The developers who establish climbing areas—defining and cleaning problems, clearing trails, creating safer landings—are after a combination of aesthetics, variety, and reliability when scouting new zones. Roy has all of that. “The rock there just demands being climbed,” Penner says. “The lines are big, and they’re extremely beautiful. The rock architecture is so varied and so striking.”

On one side of a boulder, you could find smooth, sloping handholds on pristine sandstone; on the opposite, a glossy patina on stone worn with age, presenting a different challenge. The sheer volume of rock was “mind-numbing,” Penner says. He estimates that public land in the area contains the potential for 10,000 problems.

“There is a lifetime of climbing potential out there,” he says.

Above: Camping at the Mills Canyon Rim Campground.

Above: Camping at the Mills Canyon Rim Campground.

AFTER THAT FIRST ROADSIDE STOP in 2000, Penner returned three years later to do archaeological work at Melvin Mills’s historic Orchard Ranch, a major agricultural operation that flooded in the early 1900s. It sits at the base of the primary canyon, Mills Canyon, which is part of the Kiowa National Grassland, a protected area that has been managed by the U.S. Forest Service since the 1970s. Penner spent three weeks working in and exploring the surrounding areas, which comprise a checkerboard of privately owned ranchlands, as well as parcels abandoned by settlers following the Dust Bowl and left to the government to manage.

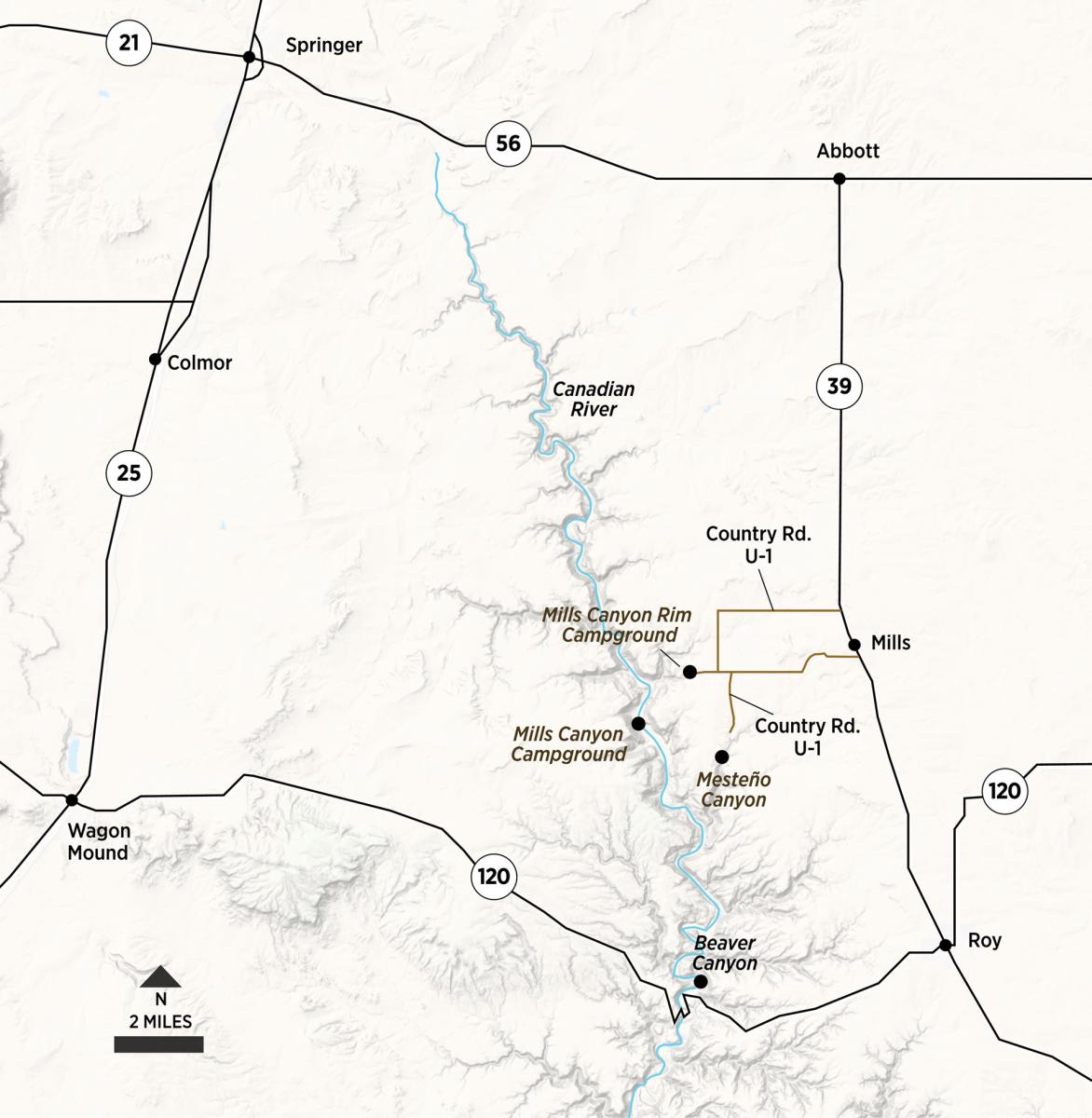

Map by John McCauley.

Map by John McCauley.

Since they became public lands, the canyons and river have attracted a slow, steady trickle of picnickers, campers, and hunters after wild turkey and the occasional pronghorn. A couple of climbers from Taos had established sport routes on a cliff band near the rim campground in the 1990s. But otherwise, the place was totally off the radar for climbers until Penner clued in a few friends.

Around 2005, they began spending as much time as they could exploring and developing the area. That early crew, which included New Mexico climbers Tom Ellis, Masumi Shibata, Grady Ball, Aaron Chavez, and J.C. Cochran, had the place to themselves for years.

“At that point, there were three cars anywhere in Roy that were climbers at any given time,” Penner says. In 2007, the Forest Service built one campground by the river and another at the rim of Mills Canyon to encourage and support more recreation. The campsites, along with the dusty roads leading from NM 39, stayed mostly quiet—which is, in part, what made it special.

“Until 2011, it was just me and my friends climbing in the canyon, and whoever thought to ask us about it,” says Penner. “That’s where we got the greatest enjoyment. I really like finding new places and the development process the best—that process of beginning.”

Above: Scenes from the Mills Canyon Rim Campground include good grub.

Above: Scenes from the Mills Canyon Rim Campground include good grub.

As word started to spread about this out-of-the-way gem, a new beginning took root. Owen Summerscales, a Los Alamos climber, first came to the area in 2012, shortly after he moved to the state. He was working off the recommendation of a friend who had tracked it down based on a few images on an obscure climbing blog, with just a few rough directions to get them to the right trailhead.

“I headed out there with my now wife, and it really felt like we were going to the middle of nowhere. It still kind of feels like that,” says Summerscales, who was overwhelmed by the volume of rock. “I realized there was a lot more than immediately meets the eye. With sandstone, it takes some time to understand the climbs. We were definitely exploring and discovering it for ourselves without any kind of guidance. It was really hard for me to understand what I was looking at until I was shown.”

Summerscales had moved to the state hoping to have a hand in developing some climbing areas, but when he connected with Penner and Ellis, he realized that a lot of the development work had already been completed. He figured his energy might best be directed into a different phase of area development: getting the word out.

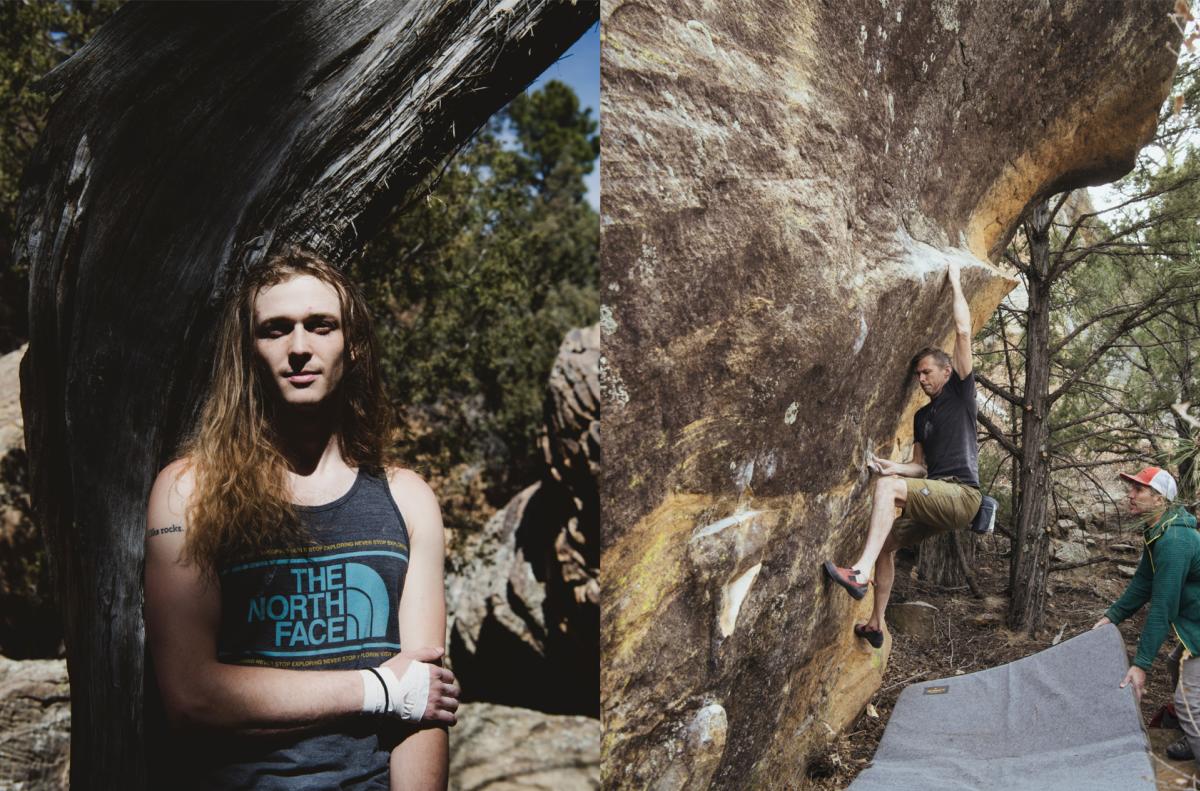

Above: Climbers Matthew Stephens; Tom Ellis and William Penner.

Above: Climbers Matthew Stephens; Tom Ellis and William Penner.

With the approval of the developers, he meticulously cataloged climbs, mapped them, tracked down first ascents, grades, and names like Mamma Jamma and Beautiful Pig, and wrote descriptions. His work—which expanded into many other bouldering areas in the state, including the Ortega Mountains, near El Rito, and the many popular sites between Socorro and Datil—would eventually become New Mexico Bouldering, the most comprehensive guidebook to date, and the first to include information about Roy. When it was published, in 2016, the area became accessible to an entirely different group of climbers.

Now the campground at the rim, nearest to the climbing, reliably fills when the weather is favorable (usually between October and April, when temperatures are cool). Colorado license plates abound, and climbers no longer need to have a personal connection within the small New Mexico bouldering community to find their way to some of the best climbs.

Above: Climber Tom Ellis takes a breather in Beaver Canyon.

Above: Climber Tom Ellis takes a breather in Beaver Canyon.

“Mills Canyon is a huge draw for both out-of-state tourists and New Mexicans,” Navas says, “which is all the more reason we need to invest in this area to protect the incredible natural resources and buoy the rural economies of Roy and Mosquero.”

To an outsider, Roy’s bouldering may look like it’s been discovered. But the guidebook lists fewer than 15 percent of the known climbs. To find the rest, you have to know where to look. Which means that two experiences of the place—one for the out-of-towners and one for the diehards—can exist in tandem. Both Penner and Summerscales say they rarely run into other climbers while they’re out, because they head to side canyons, doing the work they’ve always loved to do and leaving the established areas for the newcomers.

Even now, compared with other popular bouldering areas in the country, Roy is blissfully quiet.

Fewer people come here than to Colorado’s Front Range, which is crowded thanks to Denver’s booming climbing scene, says Penner. “I’m so happy, because I see people go to Roy and they’re freaking out on the stars, and they’re having a version of that experience that we had early on. The climbing out there is as big as you want it to be—a scale commensurate with how much you desire to actually go out and explore it.”

Eventually, Summerscales says, Roy will have more—and better—bouldering than the rest of the sites in the state combined. “In my opinion, it’s on the path to becoming one of the top-five bouldering destinations in the United States,” he says. Still, he doesn’t worry about crowds. “The people complaining about the secret being spilled just aren’t in on the other secrets,” he says.

Hubert d’Autremont explores a boulder near the Mills Canyon Rim Campground.

Hubert d’Autremont explores a boulder near the Mills Canyon Rim Campground.

GET INTO ROY

Stop at Lonita’s Cafe on your way through town for homestyle cooking and a cozy atmosphere (275 Richelieu St., 575-485-0191).

The Mills Canyon Rim Campground is accessible with 2WD, but you may want a high-clearance vehicle with 4WD for some of the more rugged roads (nmmag.us/millscamp).

Bring ample water, food, sun protection, layers, and a first-aid kit. The area is remote and rugged, and you need to be self-sufficient.

For other tips on lodgings, food, and special events, go to hardingcountymainstreet.org.

Scott Chapman spots Eli Nogueira in Beaver Canyon, a State Land Office property.

Scott Chapman spots Eli Nogueira in Beaver Canyon, a State Land Office property.

A FEW GOOD CLIMBS

The climbs in Roy are accessible but tough to find without a good guide. Owen Summerscales’s book New Mexico Bouldering (Southwest Bouldering Guides, 2016) is essential. Heads-up: You might have to scout libraries or used bookstores for a copy (or borrow it from a friend). From beginner to expert (rated V0 to V17 for difficulty on the “Vermin” Scale), fantastic climbing abounds. Here are three to tackle.

Long Ass: This V1 warm-up is located in the Jumbles, a popular section of Middle Mesteño Canyon with a high concentration of climbs. Start on the arête and traverse across solid juggy holds to a top-out that offers big views of the canyon.

Mega Roof: A lowball roof that tops out around seven feet from the ground, this spot in Upper Mesteño, about a 30-minute hike from the trailhead, is home to several fun problems. If Dust Bowl, a long V7 with more than 30 moves, is too much, try

Nobody Gets Out of Roy Alive, a V4 that involves climbing just the first half of the V7.

Calm Ethereal: Mills Canyon proper has ample climbing that’s accessible with a shorter approach hike (and slightly less rugged driving), making it a great option for those with a little less time on their hands. While there’s excellent climbing at every grade in this area, this V13 will present a welcome—and beautiful—challenge for advanced climbers.