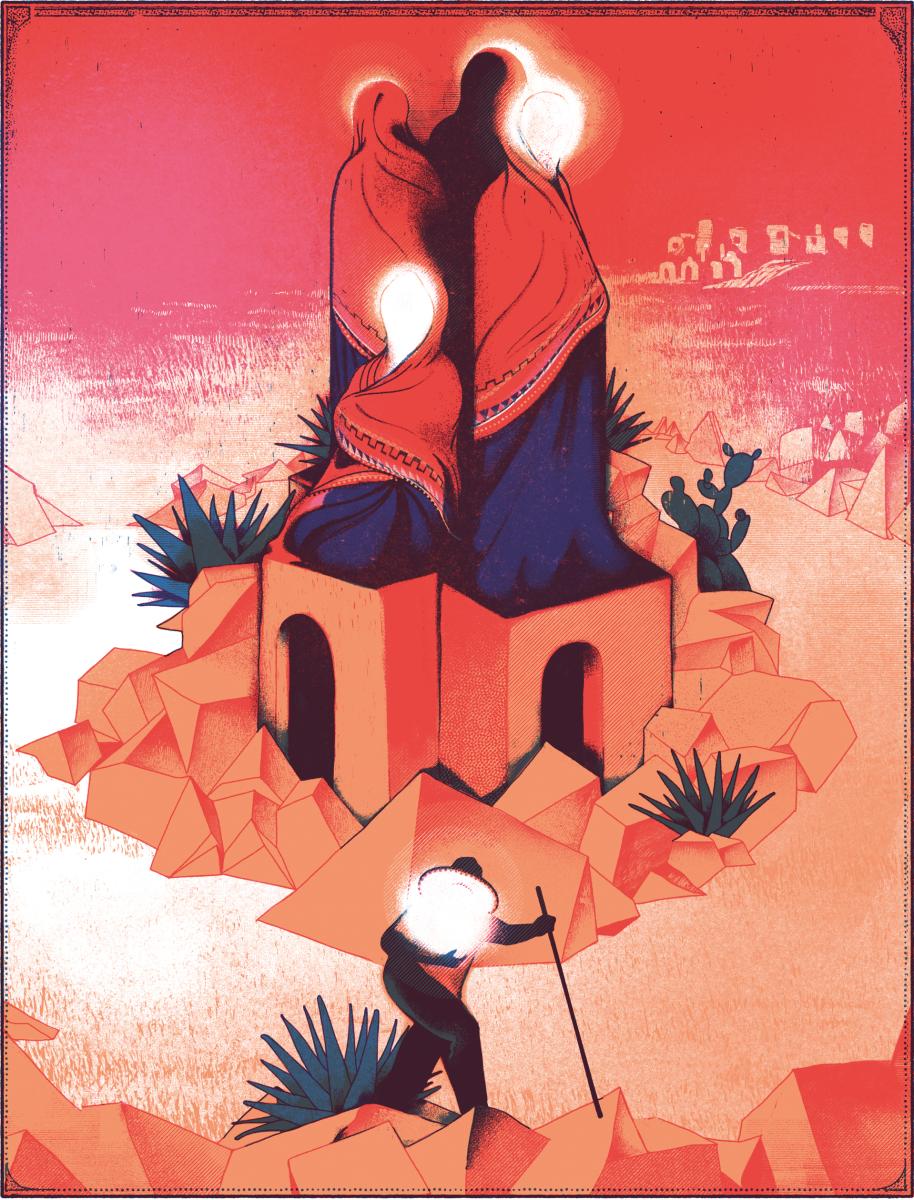

Illustration by Juan Bernabeu

WHEN I WAS A KID, we lived in a casita on my grandparents’ ranch. My parents’ nighttime stories were magical. My little brother, Beltrán, and I waited eagerly to hear them in Mom’s kitchen. The lone kerosene lantern in the middle of the dinner table flickered mysteriously. The mournful howling of coyotes near the Río Puerco added to the spookiness.

The setting was perfect for Mom’s tantalizing tales of bewitchment and evil spirits. Once Dad lowered the wick on the lamp, an eerie semidarkness descended on the kitchen. His scary stories of ghostly apparitions and phantasmagoric creatures sent chills up and down my spine.

It wasn’t long before Beltrán began cutting up, though. He thought Dad’s stories were nothing more than hocus-pocus. Mom would then turn off the lantern.

Bedtime was upon us.

The allure of a paranormal world accompanied by witches, bouncing balls of fire, and rattling chains mesmerized me as a young boy. The ghost stories that follow, though of my own creation, reflect the spirit of those I heard from my parents, my grandparents, and elders in our community.

Illustration by Juan Bernabeu

Illustration by Juan Bernabeu

A Shadow!

After supper, my cousin Juan and I saddled our horses to go visit our friend Alonso. Juan rode Pronto. I was on Bayito. “Cuidadito con las brujas,” my aunt Taida said kiddingly to us. (Watch out for the witches.)

Alonso lived beyond El Coruco (the Bedbug), a place of deserted rock houses now in ruins. The site was known for its witches, ghosts, and other supernatural creatures. On our way back, El Coruco looked really spooky in the dark with its crumbling walls and empty houses. Juan paused. He cupped his hands around his mouth and yelled.

“What witches or evil spirits? Lies! Nothing but old-timers’ tall tales.”

“Where ya goin’?” I asked.

“I’m going to look for a ghost.”

Juan vanished behind the houses, then screamed as he ran back out.

“¡Hijo ’e la patada! That thing scared the caca out of me.”

“What? What?” I asked.

“A—a—a shadow! A spooky ghost!” Juan stammered as he mounted Pronto. “Half—half—half animal, half human. ¡Pícale!” (Let’s go), he shouted, and took off. I could barely keep up.

When we got home, Juan dashed into my aunt Taida’s kitchen.

“Amá, Amá,” he said, short of breath. “I saw the cosa mala, an evil spirit. I couldn’t see its face, but the legs and feet were those of a man.”

“Ah! Ha ha,” my uncle Antonio exclaimed. “What you saw is Don Fidencio’s ghost. You see, he had a cow named Vitalia, which means ‘essential for life.’ One day it quit producing milk. He thought the mamona, the milk-sucking snake, had dried Vitalia’s udder. Oh, one more thing: Don Fidencio always rode Vitalia instead of a horse. One evening on their way home, they went by the steep waterfall overlooking El Coruco. Vitalia, without warning, leaped, and both plunged into a jonuco, a bottomless pit beneath the waterfall.

“There are those who think that Vitalia’s sadness caused her to jump, since she could no longer provide milk for her loyal friend. Don Fidencio’s body was never recovered.

“There are countless versions to the story. There you have mine. Now you boys

can tell your own story.”

Illustration by Juan Bernabeu

Illustration by Juan Bernabeu

Courtship in the Outhouse

“Hey, Primo! Wanna go with me tonight?” Tito asked.

“Where ya goin’?” I hollered as we left Mass.

“Shh! Not so loud. I’ll tell you tonight.”

My cousin Tito was 16, two years older than me. He was a mujeriego (ladies’ man), and the girls loved him. I could hardly wait to hear what he was up to. That evening he stopped by the house.

“Hey, Primo. ¿Listo?” (Ready?) “We’re going to the Griegos’ farm in La Vega. I have a date with one of the daughters.”

“Which one? There’s five of them, and they all have funny names—Albertina, Celestina, Ernestina, Justina, Martina. Their parents had -ina on the brain.”

“Justina. She’s my age. I gotta meet her in one of the large outhouses.”

Tito and I walked a mile or so to the Griegos’ farm. They had three outhouses: one for themselves, separated from the two larger ones for the girls.

“Okay, Primo. Wait inside this old storage shed till I get back.”

“But can’t I go with you? I know Celestina.”

“Nah. You’re too young. Wait till you get to be my age.”

Tito made a rustling noise as he tiptoed through Don Melecio’s pumpkin patches. The dogs started barking. He knocked at the first outhouse and whispered, “Justina.” No answer. The second one was locked from the inside. “Abre, Justina,” he said. (Open.) And Tito went in. “Oh, amor mío,” he said. “It’s so nice to see you.”

At that instant, a shadow shouted. “¡Cochino, puerco, marrano!” (Dirty filthy pig!)

The words reverberated and disappeared into the starry sky. Tito rushed back.

“Did you see Justina?” I asked.

“No, but I saw a shadow in the dark with bulging, grape-like eyes.”

“Oh,” I said. “That was Justina’s grandma. Her name was also Justina. She died a long time ago. The grandma’s shadow is Justina’s guardian angel. She protects her from boys like you.”

“Primo, how do you know that?” Tito said.

“My grandma Cinda told me.”

“But why didn’t you warn me?”

“’Cause you didn’t let me go with you so I could see Celestina!”

Read More: After leaving his rural roots, Nasario García found remnants of them an ocean away.

Illustration by Juan Bernabeu

Illustration by Juan Bernabeu

A White Ghost at El Aguaje

The spring cattle roundup was over. Junie was anxious to get home to see his mom before it got dark.

The brilliant yellow sun behind the majestic Cabezón Peak was slowly disappearing. While Grandpa hitched his horses to the wagon, Junie and his dad loaded the camping gear, bedding, clothing, and what little food was left, and they departed the campsite.

Junie was riding El Prieto, and his dad was on Moro. About two miles from the house, the father paused.

“Let’s take a shortcut by El Aguaje. Moro’s really thirsty,” he said. The horses’ slurping at the water hole lulled the father to sleep. His head slumped to his chest as he sat on his horse.

Junie then heard a rumbling noise in the dusk. He looked toward the bluff near El Aguaje, and what did he see? A white ghost on a black horse! Unable to contain himself, he hollered at his father, a short distance away, “Apá, Apá!”

“What? What?” the father said in a daze as he sat up.

“Look! A white ghost, a white ghost!”

“Oh,” he uttered calmly. “That’s the Lady of Good Hope. She comes here now and then from El Cerro de la Buena Esperanza, which you can see in the distance.”

“But why can’t you see her face?”

“Ah, your grandpa Lolo told me when I was a boy that a mother and her baby daughter drowned in this watering hole a long time ago. The infant never saw her mother’s face. So what you see is the mother’s ghost. She keeps coming here hoping to see her daughter’s spirit. The day that happens, the mother-ghost will uncover her face for the daughter to see it.”

“Apá, do you think that will ever happen?”

“Probably. You see, white symbolizes hope. That’s why the mother-ghost is wearing that long white veil.”

“Will we ever see the ghost’s face, Apá?”

“Probably not. Ghosts never show their face to humans. That’s part of their mystery. Okay, let’s go. Your mom’s waiting for us.”

Illustration by Juan Bernabeu

Illustration by Juan Bernabeu

Chaparrita and Chispa

Today is July 26, St. Anne’s Day in Los Cerros Cuates, the Twin Peaks. It’s midmorning on the festive occasion honoring women, and the village is already abuzz with three-legged races, gunnysack races, and kids trying to catch greased pigs. Anybody can participate, except men, who on this special day must stand by as spectators.

The main competition that awaits is a horse race at midafternoon, with women of all ages as the riders. The perennial favorite is Flor, a beautiful local girl whose steed is an Appaloosa.

Once Doña Adelina, the patroness in charge, emerges from her two-story adobe house, the race is imminent.

Suddenly a short, stocky person wearing a black mask and riding a gray goat that has one hind leg shorter than the other shows up. The stranger speaks in a low voice. “Who’s in charge of this race?”

Someone points to Doña Adelina. “And why, may I ask, can’t a goat join in the race?” the stranger asks.

“Because it’s a horse race,” sounds a chorus of ladies.

“What is your name?” Doña Adelina asks. “Where do you come from?”

“My name is Chaparrita, and my friend here is Chispa. We live in the open plains.”

“Okay, people,” hollers Doña Adelina. “Even though Chaparrita’s riding a goat, I will let her compete. Any objections?”

“Nah, nah. Let the stranger and her goat race,” replies Flor as the people giggle.

The ladies, including Flor, line up behind a rope on the ground—the start and finish line. Right at that instant, Chaparrita fetches a bottle of red wine from a knapsack, takes a swig, and gives the rest to Chispa, who guzzles all of it in a split second. The onlookers are shocked!

“You will race as far as the cemetery and then return here,” Doña Adelina calls out. “Ready, set, go!”

The racers take off, raising a cloud of dust. As they head back to the finish line, Flor and her Appaloosa are neck and neck with Chaparrita and Chispa. At the very last moment, Chispa lets out a loud baa (some thought it was a burp from the wine) and leaps across the rope ahead of Flor. Everyone is left scratching their heads. Chaparrita dismounts, removes the mask, and bows, revealing that it’s a man and not a woman who has won the race.

“Who are they? Devils?” a lady asks.

“No!” Another lady shouts. “They’re espíritus, ghosts that no doubt come from the Enchanted Mesa that’s close by.” As if to prove the woman’s claims, Chaparrita and Chispa disappear in a puff of smoke.

“Ah, we’ve been tricked!” Doña Adelina exclaims. “In the future, no strangers—or goats—will ever be allowed to participate in horse races on St. Anne’s Day in Los Cerros Cuates.”

Read More: Top Ten Unsolved New Mexico Mysteries

Illustration by Juan Bernabeu

A Haunted House Aglow

One summer afternoon, Grandpa Lolo and I rode horseback to visit a compadre of his in the village of San Luis. Near there, Grandpa abruptly pulled on his bridle reins and stopped.

“What’s wrong, Grandpa?” I asked.

“Nothing. You see that abandoned adobe house to the right? That place is haunted. At night you can see lights flickering.”

“Really?” I blurted out. “What are the lights, Grandpa?”

“People say they’re espíritus—ghosts, or the souls of folks who have departed this earth.”

“¡Híjole! On our way back home, if it’s dark can we stop to see the ghosts?” I asked.

“Ya veremos,” he answered. (We’ll see.)

That evening we stopped by the haunted house. I couldn’t believe my eyes.

“Grandpa, look! Flickering lights, just like you said. Not one or two, but four. Why four?”

“Ah, good question. People say that a man named Desiderio lived there a long time ago. It seems he had four wives, and each time he remarried, he built an extra room.”

“Isn’t that strange, Grandpa?”

“Perhaps, but even stranger is the mysterious disappearance of his wives. The story has it that Desiderio poisoned them and buried each one in a separate room. That’s why you see four lights.”

“¡Híjole! And what happened to him?”

“According to Don Fautino, the wise old man in San Luis, God ordered him to walk the four corners of the earth.”

“That sounds like a lot of walking, Grandpa.”

“It’s just an expression. People believe Desiderio wandered here and there in search of peace for whatever he did to his four wives. He had to find peace within his soul before he died.”

“And do you think he found peace?”

“Probably not, hijito. That’s why you also see a light—his spirit—that bounces from room to room. His soul is neither in heaven nor in hell. It’s in limbo, in purgatory.”

“And where is he buried?”

“Nobody knows. It’s also part of the mystery.”