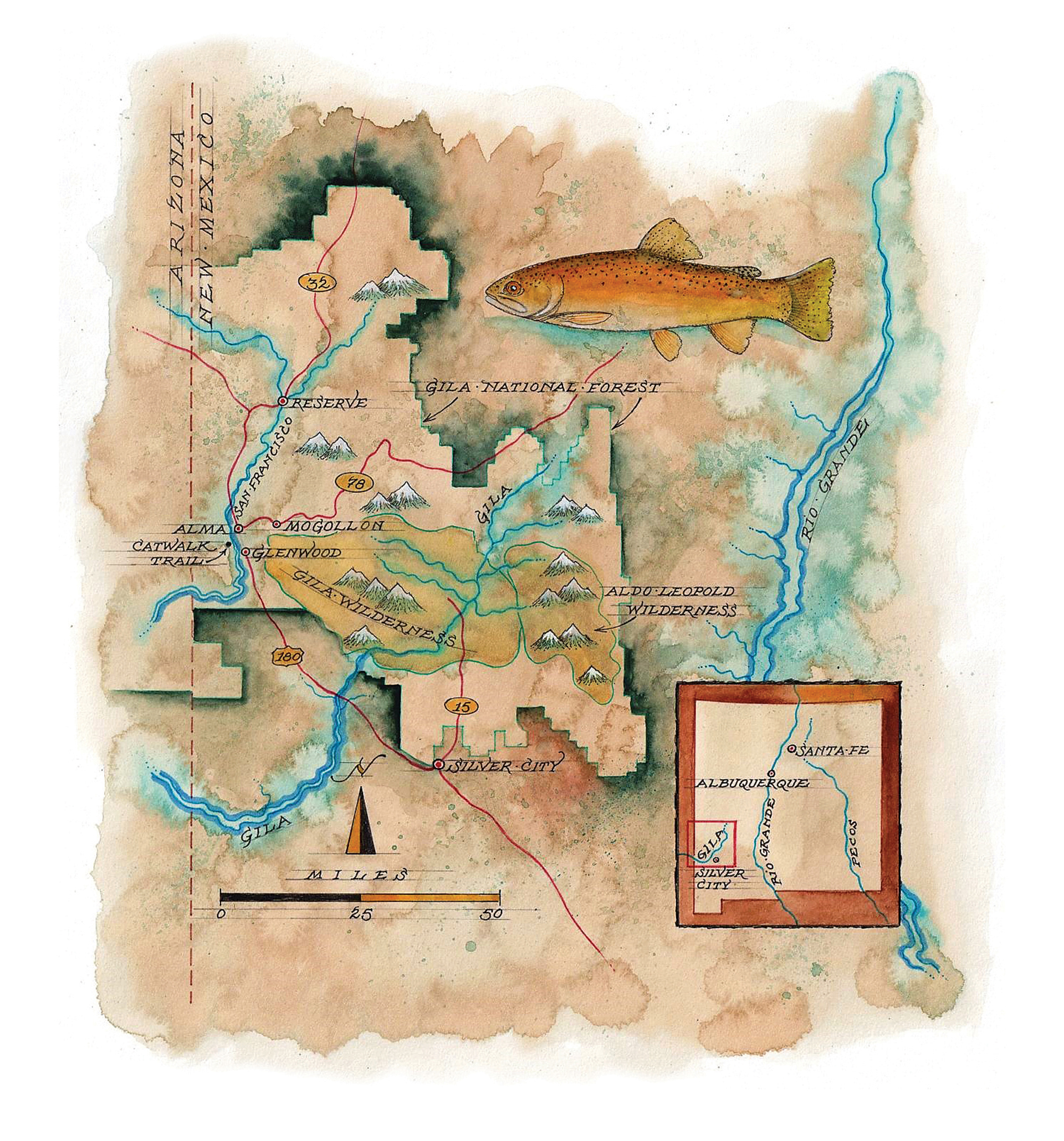

Above: Biologists have spent decades attempting to bring back New Mexico's native Gila trout. Illustration by Mike Reagan.

A CANYON WREN SANG AND THE NOTES fell one by one, as if dropping from clifftops or the branches of a towering sycamore. Midsummer heat had settled in and a few hikers had already started up the Catwalk, a popular trail in the hills north of Silver City.

The Catwalk is also a home to the Gila trout, a native fish that has struggled in recent decades. Cinda Howard, the owner of Fly Fish Arizona and Beyond, had come to check out some new water on her day off. After about a quarter mile, she left the trail and dropped down to the stream to flip dry flies into pools and seams. The fish grabbed them with abandon. She held them carefully before the release, each trout painted with a yellow splash, as if shards of sunlight or autumn leaves had fallen into the water and been absorbed by its skin.

After a couple of hours, we drove up the road to fish Mineral Creek, once the site of a gold-and-silver claim worked by James Cooney, a soldier who rode with the 8th U.S. Cavalry. Cooney’s mine drew attention to the mineral wealth of the region, but the Apache considered these hills their homeland. Local legend has it that one day Cooney and another settler rode to warn residents in Keller’s Valley, around today’s town of Alma, that Victorio and his warriors were approaching, but they never made it back to their cabins. We passed his grave, blasted into a boulder, on the way to the trailhead.

Fishing for Gila trout is like walking through time itself, from the slow grind of geology to the mining booms of the last century. The trout lives within the cooler, higher waters of the Gila’s New Mexico portion. Altogether, the Gila traces a path that begins in the Black Range of New Mexico and flows across the breadth of Arizona before joining the Colorado River near Yuma.

Drought, overfishing, overgrazing, wildfires, and the undertow of history have taken their toll on Gila trout. Biologists have spent decades trying to bring them back. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish, the U.S. Forest Service, and other groups have studied the fish, all the way from its mountainous habitat down to its DNA, and it appears the species is getting traction.

As we left the water and started up the winding highway, the summer heat faded and the day came back in bits of memory—the deep canyons, bent oaks, blackberry brambles, and bear scat along Mineral Creek. The sound of water. A yellow flash.

Above: The Gila National Forest’s sheer cliffs, caves, and running streams craft inspiring landscapes. Photograph by Ryan Heffernan.

BIOLOGISTS HAVE USED A VARIETY OF TOOLS TO restore these fish—pack mules, helicopters, genetic research, microchipping, and a state-of-the-art hatchery. But one of the best weapons at their disposal may be how Gila trout take to local streams. The fish are beautiful, resilient, and a pleasure to angle for, as much a part of the state’s fabric as the Gila River itself.

When glacial epochs rearranged the New Mexico landscape some 25,000 to 50,000 years ago, the Gila trout’s ancestors found a home. They were here when the Mogollon made their cliff dwellings and the first Apache clans arrived. They were here when Spain claimed New Mexico as part of its territory and when American trapper James O. Pattie came through in search of beaver skins. They were here before the first cowboy tracked a lost calf, before the first miner pitched his tent, before the first saloon or cathouse opened its doors.

In 1896, if someone in the region wet a line and caught a fish, this was the prize they caught, and they reported catching about a fish a minute. The fish varied from a half pound to a pound and averaged about 12 inches, according to Fish and Wildlife’s 1993 Gila Trout Recovery Plan. But just a couple of decades past that golden era, the fish were in trouble. By 1923, the state was trying to raise Gila trout at Jenks Cabin Hatchery, near the confluence of White Creek and the Gila’s West Fork.

It was about this time that conservationist Aldo Leopold, in published articles and in his work with the Forest Service, scribbled out a plan to further preserve a large section of the existing Gila National Forest. He called it a wilderness, and national wilderness areas began sprouting all across the country, including this one, the Gila Wilderness, the nation’s first. It was later reduced in size, leaving its roughest and wildest portion as the Black Range Primitive Area, but in 1980, that was reborn as the Aldo Leopold Wilderness.

Read more: On the hunt for the iconic Mearns quail in southwestern New Mexico.

Leopold believed it would be easier and cheaper to preserve both wilderness and wildlife through planning and forethought than to restore it after it was gone. That might seem obvious, but what should go into such planning and forethought was up for grabs. Leopold’s time was one of rapid growth, road building, and expanding outdoor tourism. Although we think of him as a founding father of modern wilderness and environmental thought, his ideas evolved in a tangle of thorny philosophical questions about game management, natural resources, and fire suppression. Decisions made in his time have reverberated, through time and through the forest. Through the Gila itself.

For example, with game populations falling, there was talk of raising animals for the benefit of sportsmen, who would then hunt on game farms. But Leopold and others opposed this idea. Wildlife conservation prevailed, for the most part, and America’s wildlife remained wild.

On America’s rivers, where native trout populations were falling, it was a different story. Biologists were not shy about stocking non-native trout, and anglers were not picky about their catch. Before long, western streams were full of brown trout and rainbow trout, both of which threatened natives, for different reasons. Aggressive, ill-mannered, fall-spawning browns can elbow aside natives and establish wild populations if left alone. Rainbows don’t just take over a stream; they take over the gene pool. They spawn in the springtime, when native Gila, Apache, and cutthroat trout spawn. By 1966 New Mexico’s streams were full of hybrids, and the Gila trout was considered an endangered species.

While biologists managed trout, foresters tried to manage forests. For decades, there was heated discussion of the role of fire in these forests. Some said wildfires were part of nature and a limited amount of controlled burning was healthy for forests. Professional foresters sniffed that this was “Paiute forestry” and had no place in modern forest management, which valued timber above all, environmental historian Paul Sutter wrote in The Western Historical Quarterly. The Forest Service chose to suppress fire.

Mines played out, people moved on, boomtowns slumped, fell into disrepair, and became ghost towns. The forest grew thicker, tourists kept coming, and the Gila trout retreated to higher elevations.

As fisheries biologists tried to untangle the genetics of trout, the Forest Service began to reexamine its policy on fire suppression. Research showed there was something to that Paiute forestry thing, and the agency could better manage forests with light burning. With a century of fuel on the ground and towns firmly established in and around the forests, figuring out how and where to burn was not easy. Meanwhile the agency dithered on the details. By the late 1980s, fire started doing the job itself. Several wildfires disrupted Gila trout recovery efforts, including 2012’s Whitewater Baldy Fire, which took out the Catwalk’s walkways but also devastated rainbow trout populations in Whitewater Creek.

Biologists decided to take the rainbow’s loss as an opportunity to advance their Gila trout efforts. Plans called for removing the few remaining trout, tending a new generation of Gila trout at hatcheries, and then reintroducing them. Today, the Catwalk’s namesake walkways are being rebuilt, trail maintenance continues, and the fish are thriving. Some 25,000 are stocked in the region’s waterways each year. They claim more than 100 miles of habitat and attract anglers whose license fees help fund further restoration efforts.

Above: The fish are beautiful, resilient, and a pleasure to angle for, as much a part of the state’s fabric as the Gila River itself. Illustration by Mike Reagan.

TWO WILDERNESS AREAS NOW LIE AT THE HEART OF THE GILA National Forest: the Gila Wilderness and the Aldo Leopold, where headwater streams tumble out of the mountains and into the hill country below. On a map, NM 15, out of Silver City, appears to stab into this wilderness. But it takes about two hours to drive the narrow, winding road, which ends at Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument and a lazy river valley where trailheads beckon and three forks of the Gila meet.

During the winter, Game and Fish stocks the Three Forks area with Gila trout, says biologist Ryder Paggen. The fish are gone by summer; Paggen suspects they head to higher elevations and cooler water, but nobody really knows.

Another highway out of Silver City, US 180, skirts the western reaches of the Gila National Forest and runs within a stone’s throw of the village of Reserve, then snakes over to Arizona. It’s lonely country, though you’ll pass a few small towns—Cliff, Glenwood, and Alma—along with juniper hills, ranches, clusters of oak, dirt roads, campgrounds, and a few places to grab a bite or a bag of ice.

On a second trip this past fall, Cinda Howard and I came in for the fish, but lingered for the towns we hit along the way. We entered New Mexico from the north, drove south, and dropped into the Adobe Café & Bakery, just outside Reserve. I ordered a tasty cinnamon roll and a latte, fuel for the morning, and moved on. We passed the Cosmic Campground, a primitive campground with telescope pads and a 360-degree view of an amazingly dark sky, a reminder that western New Mexico has some of the best stargazing in the world.

Read more: Norman Maktima made history as a champion angler with Native roots.

By this time, the summer heat was a memory. When we got to the Catwalk, we pulled on waders and long sleeves in the parking lot. The canyon still had some autumn color. One tree stood alone in the shade, yellow and braced for winter. The fishing was slower, but we caught a few.

Afterward, we went back up the highway and turned at NM 159, also known as Bursum Road, a winding blacktop that turns to bone-rattling gravel, then climbs out of the high desert, passes through the ghost town of Mogollon, and continues higher into the mountains.

There’s not much left of Mogollon, which sits about 75 miles northwest of Silver City. The mining town once had five stores, seven cafés, a variety of boardinghouses, two hotels, a deputy sheriff, two doctors, a few lawyers, schoolteachers, 14 saloons, a couple of joyhouses, and a church or two, according to F. Stanley, author of The Mogollon New Mexico Story. Stanley also noted that in 1882, the mining camps were located in the canyons of “six small tributaries of the San Francisco … Dry Creek, White Water Creek, Silver Creek, Mineral Creek, Copper Creek and Deep Creek.” All, he wrote, were “handsome trout streams.”

These days, Mogollon has a store, a restaurant, and a hotel in a historic building, but the proprietors roll up the sidewalks from November through April. Still, we were taken in by the rustic charm.

We tarried longer than we should have, eating lunch on the tailgate and walking around. The Silver Creek Inn looked charming, and we spoke briefly to a caretaker, one of the few Mogollon residents still around, before she vanished into the adobe building. I made a mental note to come back between May and October to spend a night when the inn is open.

We drove on, stopped to watch a few mule deer that browsed on the edge of the ghost town, then continued on. Before long the road reverted to washboard gravel. Willow Creek, another Gila trout destination, was up the road, but we were running out of time. We took a short hike up Trail 206 to stretch our legs, then it was time to go.

Mogollon looked all but deserted in the gathering darkness as the temperature dropped and a pale moon cleared the treetops. The trout, well, they’re still out there, where they’ve always been, where sycamores grow tall and canyon wrens sing, where the Mogollon once walked and the Apache rode, where the road goes on forever, into the cordwood horizons and a boundless sky.

GILA GETAWAY

Throughout the Gila region of New Mexico, services are few and cellphone reception is spotty. Anglers can get a fishing license online or in Silver City (Walmart).

There are a few places to eat and stay, however. Mogollon’s busy season runs from mid-May through mid-October. The 1885 Silver Creek Inn offers rustic charm in a rare two-story adobe building. It’s smoke-free and pet-free. Other Mogollon attractions include the town museum, a historic cemetery, and the Purple Onion Cafe.

In Alma, the Alma Store has a restaurant, snacks, ice, drinks, and gas.

The Adobe Café & Bakery, just outside Reserve, has tasty baked goods, espresso, and chocolate truffles. Its sister restaurant, the Adobe Does Cafe, serves pizza, sandwiches, and smoky barbecue. Also stop into Studio Verde, a gallery that represents local artists and craftspeople.

To hook up with a fly-fishing guide in the region, try these options: Cinda Howard, Fly Fish Arizona and Beyond, in Greer, Arizona (480-217-5089, flyfisharizona.com), and Ed’s Fly Shop, in Silver City (575-313-3137).