THE DOWNCAST DEMEANOR of William Herbert “Buck” Dunton’s offspring in his painting My Children (circa 1922), created shortly after their parents divorced, lends it an elegiac tone. Despite the somber emotions emanating from the canvas, the painter’s greater glory—the West—shines through. Dusky skies hint at the beginning or end of a long day. Horses wander rocky outcroppings in a high desert landscape. Dunton’s children and their horses are rendered with a rhythmic series of strokes that match those of the sagebrush that surrounds them, making them one with the landscape in a vivid scene that’s heightened by dramatic contrasts between the foreground and the background.

“Dunton’s family was important to him, and he flourished in Taos,” says Betsy Fahlman, an adjunct curator at the Phoenix Art Museum and co-curator of the exhibition William Herbert “Buck” Dunton: A Mainer Goes West, now at the Harwood Museum of Art, in Taos. “But his wife, Nellie, did not share his enthusiasm for the Southwest, and they were divorced in 1920.”

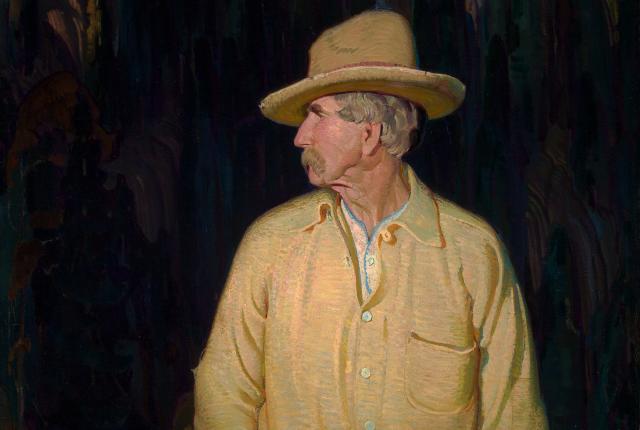

Dunton is known for his paintings and illustrations of ranch life, rodeos, and, most notably, cowboys. These depictions played into romantic notions of the West. But beneath the surface was something real. The hidden life of his subjects is hinted at, for instance, in the reproachful smirk of a goatherd in Dunton’s Pastor de Cabras (1926).

Born in Augusta, Maine, in 1878, Dunton worked as an illustrator, contributing to Harper’s and other popular periodicals. He visited Taos in 1912 on the recommendation of Ernest Blumenschein, his instructor at the Art Students League in New York. Dunton was a founding member of the Taos Society of Artists and one of the Taos Six, a group that included Blumenschein, Oscar E. Berninghaus, E. Irving Couse, Bert Geer Phillips, and Joseph Henry Sharp.

“Buck Dunton helped define the West,” says co-curator Nicole Dial-Kay, adding that his works rarely travel. The Dunton show was programmed in conjunction with the Harwood’s Outriders: Legacy of the Black Cowboy. Viewed on the same visit, the two exhibitions offer contrasting and complementary glimpses of Western life.

Read more: Cowboys and trains changed New Mexico—and still spur our dreams.

WILLIAM HERBERT “BUCK” DUNTON: A MAINER GOES WEST

Through May 21

Harwood Museum of Art, 238 Ledoux St.,

Taos; 575-758-9826, harwoodmuseum.org

THE HARWOOD AT 100

Journey through a century of history as New Mexico’s second-oldest museum, the Harwood Museum of Art, in Taos, celebrates its 100th year. The museum’s Centennial Exhibition, which will be mounted in each of its nine galleries, opens on June 3. The exhibition includes 200 works of art drawn from the Harwood’s 6,500-object collection, 200 books from the former Harwood Public Library, and loaned works by Ansel Adams, Georgia O’Keeffe, Paul Strand, and others. Artists Burt and Lucy Harwood purchased the historic museum property on Ledoux Street in 1916; the Harwood Foundation was established in 1923. The museum’s first exhibition opened a year later, a decade before the town of Taos was incorporated. Today, the Harwood preserves the legacy of regional Native American and Hispano/a artists, the Taos Society of Artists, the Taos Moderns, and regional contemporary artists. That mission could soon grow larger. “Harwood is using this opportunity not only to share its history and its collection with the visitors, but also to put the institution on a new path—one that aims to be more inclusive and community-focused,” says Juniper Leherissey, the museum’s executive director. “Reflecting on our history gives us a chance to envision the future role of Harwood in the community.” harwoodmuseum.org/centennial