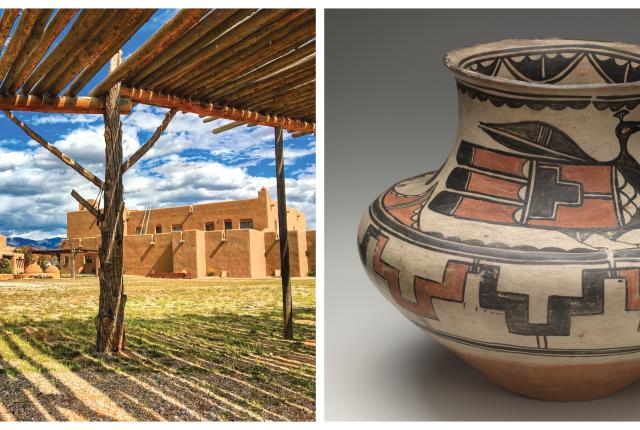

Above: The Poeh Cultural Center was founded in 1988 by Pojoaque Pueblo. Right: A Tewa Pot. Photograph Courtesy of Poeh Cultural Center.

While museums are usually built to preserve objects in perpetuity—to secure them in archives with limited public access—the Tewa worldview has it different: For objects from the past to remain alive, they must be handled daily. They speak and listen, imparting their knowledge to others. Pottery is a prime example. “Pots are elders telling stories, and those of us listening learn values that help sustain our communities,” says Karl Duncan, executive director of the Poeh Cultural Center, in Pojoaque.

When, in the early 20th century, George Gustav Heye began collecting material culture from indigenous peoples, including the Tewa, he forever changed the life path of a certain number of pots. His attempt to preserve those pots in the Museum of the American Indian, in New York, effectively cast them into dormancy.

Now, 100 of the pots that Heye amassed from six pueblos (Pojoaque, San Ildefonso, Ohkay Owingeh, Santa Clara, Tesuque, and Nambé) are returning home and reuniting with the descendants of their makers. After several years of negotiation, the institution that Heye founded, now the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, has agreed to a long-term loan with the Poeh for the exhibition Di Wae Powa: Return of Historic Tewa Pottery from the Smithsonian. It’s been a drawn-out journey. Tewa representatives for each of the six pueblos have visited NMAI over the past two years, culling examples from between 1850 and 1930 and speaking to the pots in Tewa to remind them of their language and thereby prepare them for the journey home—Di wae powa is Tewa for “they came back.”

When the pots go on display this month, it’s with a new approach to presentation in mind, not under glass, but open—accessible—allowing people from across Tewa Country and beyond to handle and learn from them. And because a pot’s maker is recognizable by style alone, “the real magic,” Duncan says, “will come when elders from the community start telling stories about the pots” and who made them. The Poeh, he says, “is becoming a Tewa learning center where pottery is the focal point and where community is the number-one priority.”