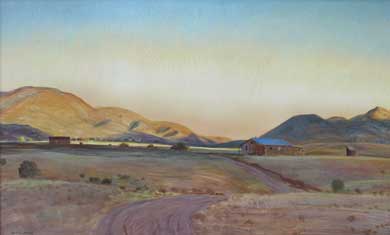

The Valley Near San Patricio, by Peter Hurd, inset to a recent photo taken at the ranch.

The Valley Near San Patricio, by Peter Hurd, inset to a recent photo taken at the ranch.

Read Hurd’s 1961 essay about the New Mexico landscape.

HURD–LA RINCONADA GALLERY AND GUEST HOMES

Six guest homes range from one to three bedrooms in size. The next art workshop will be held in July, with ENMU drawing instructor Marty Lane and Michael Hurd; contact the gallery for details. The gallery sells the art of Andrew, Henriette, and N. C. Wyeth and Peter and Michael Hurd. (800) 658-6912; wyethartists.com

ROSWELL MUSEUM AND ART CENTER

Peter Hurd’s hometown museum proudly hosts a permanent exhibition called Hurd & Wyeth: Picturing the Hondo Valley in the Founders Gallery. (575) 624-6744; roswellmuseum.org

AREA ATTRACTIONS

Check out Ruidoso-area activities in “Go for It,”; and consider our three-day road-trip itinerary through Ruidoso, Lincoln, San Patricio, and Tinnie: mynm.us/roadtripruidoso.

NEDRA MATTEUCCI GALLERIES

in Santa Fe represents the work of Peter Hurd, Michael Hurd, and Henriette Wyeth. matteucci.comWYETH HURD GALLERY

in Santa Fe also represents Peter, Michael, and Henriette, along with four generations of Wyeth artists. (505) 989-8380; wyethhurd.com

THIRTY MILES EAST OF RUIDOSO, along US 70, a guest ranch offers visitors the chance to play house—on the range—in a sweet, homey abode. Admittedly, the majestic surroundings upstage the six houses’ charms. At Las Milpas, guests wake up to the sun rising over the hills and valley. A panoramic view of the Hondo Valley awaits Orchard House guests, along with rolling green pastures dotted with leafy trees and a scattering of cows. Apple House is a stone’s throw to a gentle stream.

Along with grade-A landscape, the ranch offers guests the chance to enter a remote, intentional world created in 1932 by two members of America’s First Family of artists: Henriette Wyeth and Peter Hurd.

Today, you could find the Hurd–La Rinconada Gallery and Guest Homes website online, or stumble upon them on Airbnb and make a reservation. You could have a memorable time roaming the vast property: walk down a mile-long dirt road next to a stream and spot elk and coyotes on trails that crisscross the 2,300 acres.

You’d enjoy it, but without learning the lore, you’d be missing out.

In 1904, young Massachusetts artist N. C. Wyeth decided he needed to improve the accuracy of his Western-themed illustrations. So he got a job as a cowboy in Colorado, where he moved cattle and toiled at ranch chores, absorbing imagery within sweaty clouds of sun-gilded dust. Continuing his Western cultural immersion, he entered Navajo country, in the Four Corners area, and stayed for a piece. This research would soon inform his drawings for the Saturday Evening Post and other clients.

But before he could do that, his stash of wages was pilfered.

Instead of asking his mother, an acquaintance of Thoreau and Longfellow, to send him some money, he took a job delivering mail between Two Grey Hills Trading Post in Tohatchi, New Mexico Territory, and Fort Defiance, Arizona. (This experience resurfaced in an illustration he made in 1907: an ad that showed an Old West mail carrier on horseback putting a package into a mailbox made from a wooden Cream of Wheat crate.)

What began as research became a labor of love. In a letter he sent back home, N. C. wrote, “The life is wonderful, strange—the fascination of it clutches me like some unseen animal—it seems to whisper, ‘Come back, you belong here, this is your real home.’” The call of the East Coast was stronger, though, for along with reuniting with his family, it was there that he could make a name for himself as the creator of thousands of paintings and illustrations—luminous images that graced books, magazines, calendars—all notable for the same intricate authenticity with which he imbued his Western scenes. N. C. married Carolyn Bockius, and they raised a family of five children groomed for artistic success. According to a 1977 New Mexico Magazine article, “A Wyeth in New Mexico,” by Mary Carroll Nelson, it was “a household that thought it was normal for everyone to draw all the time and exhibit at age ten.” It was a homeschooled, “cloistered, all-for-one, one-for-all family with a phenomenal father.” They entertained a circle of high-flying friends, including the actresses Helen Hayes and Mary Pickford, and even F. Scott Fitzgerald.

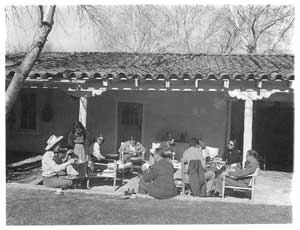

The courtyard of the Wyeth House.

The courtyard of the Wyeth House.

Peter Hurd (in hat) hosting guests there, c. 1950.

The very same year, 1904, that Wyeth embedded himself in Western life, Peter Hurd was born in Roswell. He attended New Mexico Military Institute and was appointed to West Point, planning to become an officer. Two years in, the desire to be an artist vanquished his soldier dreams, and he transferred to Haverford College, near Philadelphia. N. C. Wyeth was one of his idols; Hurd boldly sought him out in nearby Chadds Ford. Wyeth recognized enough talent in his work to take him on as an assistant and apprentice for what amounted to a decade. His cowboy boots and New Mexico provenance surely helped endear him to N. C.

“My father was a wonderful showman,” says Michael Hurd, who lives on the ranch and is an accomplished landscape artist very much in his father’s tradition. “He loved people and he loved to talk to people. He was very well-read, and he also loved to play his guitar and drink tequila.”

N. C. fostered Peter’s career as if he were one of his sons, referring him to clients for illustration assignments that Wyeth didn’t have the interest or time to do. Although N. C. had sons and daughters who were actively training as artists, he could afford to be generous; they were living in the golden age of illustration, when full-color reproduction techniques had the kinks worked out, magazine circulations were booming, and the demand for graphic art was insatiable. Peter also contributed in his own way, introducing N. C. and his son Andrew Wyeth to painting with egg tempera, a method they went on to use frequently. Andrew used tempera in his iconic Christina’s World, which is one of the most well-known American paintings of the 20th century and hangs in the Museum of Modern Art.

In 1929, Peter became more than a protégé when he married N. C.’s daughter Henriette. The young marrieds returned to New Mexico each summer, creating a homestead in San Patricio that they named Sentinel Ranch, before deciding to relocate there permanently. N. C. was not pleased about it, but he couldn’t exactly feign bewilderment.

Come back, you belong here, this is your real home.

Ina Sizer Cassidy, who wrote the "Art and Artists of New Mexico" Column in this magazine for many decades and was married to Santa Fe Art Colony founder Gerald Cassidy, reported in a February 1941 article, “Here each maintains a separate studio, for the two members of this unusual art team are artists in their own right, each maintaining their own identity as a creator, which is as it should be but is so seldom found. Peter Hurd attributes much of his success in fresco to his wife’s understandingly constructive criticism, while she acknowledges his help as freely.”

Clockwise from above: The Hondo Valley as seen from the gallery. Henriette Wyeth’s portrait of her daughter Carol Hurd. Las Milpas house. A view into the sunroom at Wyeth House. A white picket fence surrounds Orchard House.

|

|

|

The Hurds settled in, forging an alchemy of East Coast culture and Southwest flavor that endures to this day. Peter taught local cowboys and ranch hands to play polo on a dedicated field with stands, occasionally bringing in professional polo players to form a team called the San Patricio Snake Killers, which competed against squads from El Paso, Juárez, and his alma mater, Roswell’s NMMI. He wandered around in the mountains, locating pigments for his paints—deposits of golden ocher, red iron ore, and virgin azurite that he ground to access the blue of the Old Masters. And he connected with innate conservationist beliefs, terracing his land in 1938, plugging up arroyos to decrease water loss, topping them with native plants, and transplanting trees. In this magazine’s January 1951 issue, Peter was the subject of an article called “Artist with a Green Thumb,” which described him as contributing cover paintings for Country Gentleman and articles to agriculture magazines.

Henriette had her own way of hunting for color. She would seek out scarlet penstemon, verbena, coreopsis, desert asters, wild daisies, pale yellow primroses, and goldenrod for still lifes and as accents in portraits. The gallery that represented Henriette in New York sent a steady stream of clients to come to the ranch and have their portraits painted.

But they weren’t the only guests.

“Mother loved to entertain, and as I said, my father was a showman,” says Michael Hurd. “My parents would have a luncheon, and you’d see a cowboy next to a banker from New York, next to Helen Hayes, next to an editor from Life magazine.

“When I was a very little boy, I remember that Bob Crosby, a world champion cowboy, was there. The maids came in and served a spinach soufflé my mom was really well known for. Bob said, ‘Cowboys don’t eat cow slobber.’ There was a stunned silence, and then my mother started to laugh,” which broke the ice. “He was silly and funny and didn’t mean to be gross. That’s just how it was. Very eclectic, a lot of fun, not stuffy, really interesting. As a kid growing up, having people like that around was a living education. Once, the prime minister of Thailand gave me the aluminum covers from his cigars, and I made a pontoon boat out of them.”

However, as Henriette said in our 1977 article, she and Peter “stayed away from the Santa Fe and Taos groups. There was so much talk, so many exchanges of ideas. You shouldn’t let yourself leak out. [Art] should be private, like lovemaking. It’s a very severe process, taking a long time, to learn to be an artist.”

During World War II, Peter left the ranch in Henriette’s and the staff’s hands to sketch scenes as a war correspondent for Life. In the fifties, WPA commissions took him on the road frequently to paint large frescoes in public buildings all over New Mexico and Texas (including one that moved from Texas to New Mexico very recently, the focus of our February feature “Putting the Art in Artesia,” mynm.us/ArtArtesia). His Alamogordo post office mural, titled Hymn to the Two Great Blessings of New Mexico: The Sun and the Rain, recalls N. C.’s early gig as a Western mail carrier and Peter’s own passion for the environment. In 1967, he was commissioned to paint President Lyndon B. Johnson’s official portrait. Johnson famously rejected it, but it was nonetheless acquired by the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. Henriette painted Pat Nixon’s official portrait in 1978, which was received far more favorably.

Henriette and Peter did not encourage Michael to be an artist, a break with the N.C. Wyeth tradition. Michael pursued a singing career, performing with the Kingston Trio, and worked in real estate in Chicago before he bought a one-way ticket back to New Mexico, moved onto the ranch, and picked up a paintbrush. “My parents opened the door to other possibilities,” Michael says, “but I had to walk through the wall.”

Starting humbly, he took a figure-drawing class at New Mexico State University. “One of my first drawings was of a standing figure, nude. I showed it to my mother, and I knew that if she took longer than 15 seconds to respond, I would be in trouble.

“She looked at it for 18 seconds. She said, ‘The poor girl. Is her right arm really six inches longer than her left?’ We both had a big laugh about it. She had that ability to help you see it without crushing you. You wanted to go back and do it well.”

Right around the time that Peter Hurd passed away, in 1984, Michael decided to build on what his parents had established. The gallery was completed in 1985; he restored old adobes on the property in the late eighties and also built one new house from the ground up. “It’s a money pit to restore old adobes. Plumbing, wiring, windows, roofs—it’s an infinite commitment of money and time, but it’s well worth it.”

The Apple House.

The Apple House.

The Apple House, a one-bedroom with cheerful furnishings, used to be an above-ground apple storage structure. La Helenita, the new house, is named after their old family friend, the actress Helen Hayes. It’s a stately structure with Cape Cod lines, though made tidily of adobe bricks. (Hayes bought Michael’s first painting; it hangs in her family house in Nyack, New York.)

The pitched-roofed architectural styles date to the Civil War. “When the Union Army came here and built Fort Stanton, they brought with them from Virginia a particular style, the 12/12 pitched roof. It was adopted by a lot of the houses in Lincoln, and buildings built by the railroad,” Michael says. It’s practical, “because we’re affected by rain and snow here, too.”

Michael frequently paints on the property—never from photographs, only from scenes around him. One of his watercolors, Monsoon, depicts the Apple House on its small hill amid rolling countryside, a stabbing trident of lightning flickering in the overcast sky. He likes the challenge—it keeps him limber. “If you have discipline, you have wings,” Henriette, who died in 1997, once said. Henriette received the Governor’s Award for the Arts in 1981; in the early nineties, she and Michael taught workshops as part of the master’s program at Santa Fe Art Institute, alongside Richard Diebenkorn and Helen Frankenthaler.

Rio Ruidoso runs through the ranch.

Rio Ruidoso runs through the ranch.

Airbnb has brought new clientele to the ranch, people who are lured by the beauty and remoteness, not necessarily because they’re drawn by the Wyeth-Hurd mystique. The greater variety of guests harks back to the glory days of the ranch, when a cowboy, a banker, a Hollywood actress, and a Thai prime minister could show up on a par-for-the-course luncheon guest list.

“A group of guys came to stay at my mother’s house last weekend,” Michael says, referring to the Wyeth House, Peter and Henriette’s former residence. “I spoke briefly to them. They were Special Forces guys about to go over to Afghanistan. One likes writing, one’s a musician—they extended their stay and enjoyed another day of skiing.” A demonstration of classic Wyeth-Hurd hospitality: “We offered them a free stay when they get back from overseas. I just thought, ‘Let’s give them something to look forward to.’”

—Candace Walsh is the author of the NM-AZ Book Award–winning Licking the Spoon: A Memoir of Food, Family, and Identity (Seal Press). She’ll be teaching “Secrets of Successful Memoir” at the UNM Summer Writers’ Conference July 30–31 (taosconf.unm.edu).