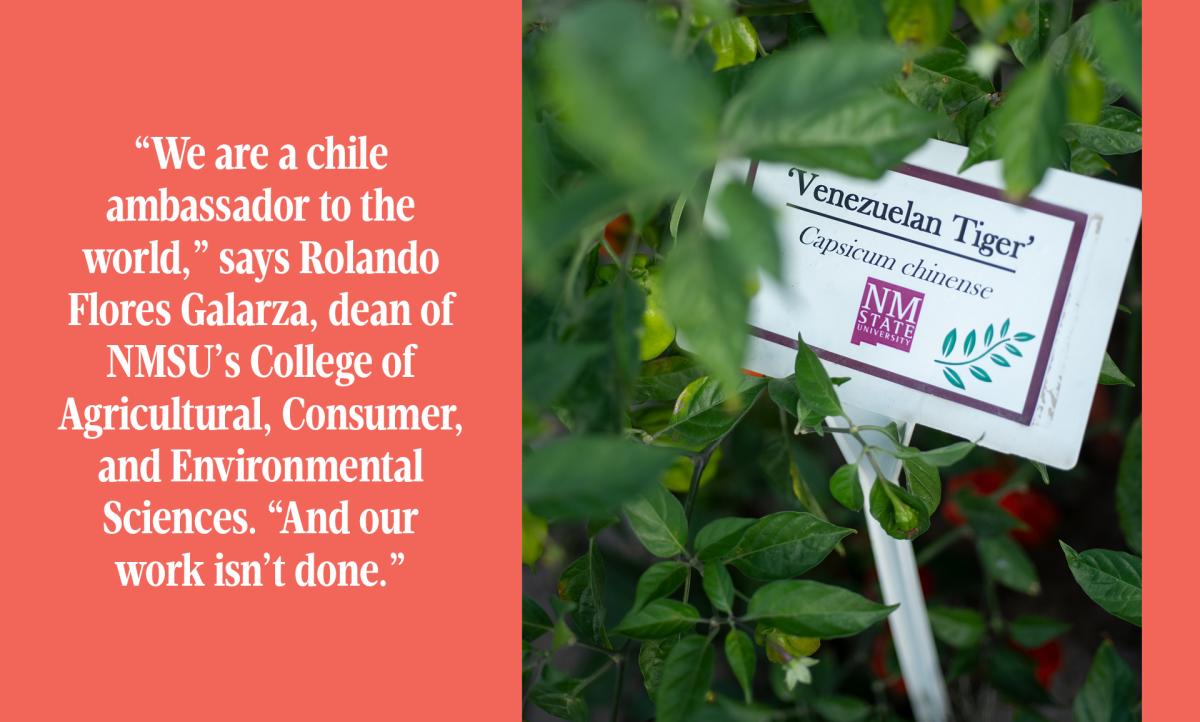

Above: The teaching garden at New Mexico State University’s Chile Pepper Institute tests 150 different varieties every year.

BEHIND AN INCONSPICUOUS DOOR in the unremarkable hallway of a standard university building lies a one-room wonder. There, a former classroom bursts with racks of colorful seed packets, shelves of salsas, walls of posters, and an array of gardening guides.

Since its inception in 1992, New Mexico State University’s Chile Pepper Institute, in Las Cruces, has grown from a cramped closet to this shop, along with an annual teaching garden, test plots, laboratories, a seed bank, high-tech equipment, and researchers who explore every aspect of soil, water, disease, nutrition, flavor, heat, harvesting, and commercial processing. They partner with local growers as well as others in Japan, Israel, India, Mexico, and elsewhere. They develop new varieties, study climate change, and help promote a fruit native to South America’s tropical rainforests that has worked its way into nearly every cuisine on the planet.

“We are a chile ambassador to the world,” says Rolando Flores Galarza, dean of NMSU’s College of Agricultural, Consumer, and Environmental Sciences. “And our work isn’t done.”

The university earned its chile acclaim with research originating in the early 1900s, when horticulturist Fabian Garcia introduced New Mexico 9, the first chile bred specifically for a dependable pod size and heat. Garcia, a native of Mexico, laid the foundation for what has grown into a $50 million industry in his adopted state.

Those burlap bags of green chiles that most of us eagerly await each fall to restock the freezer? They’re but a blip of the total. Fields that stretch from Hobbs to Deming and from the Mesilla Valley north through Lemitar and Chimayó feed an international appetite for salsas, spices, medicinal balms, dyes, and more.

Above: Paul Bosland in the Chile Pepper Institute’s teaching garden, where varieties range from international favorites to multicolored ornamentals.

Above: Paul Bosland in the Chile Pepper Institute’s teaching garden, where varieties range from international favorites to multicolored ornamentals.

“The Tabasco sauce we find in the stores, that’s from a variety of cayenne chile grown in Las Cruces, fermented in the Mesilla Valley, and sent to Louisiana,” Flores Galarza says. “Deming has the largest chile-processing facility in the world.”

That jar of kimchi in the fridge just might contain NuMex Sandía chile from a field in Hatch.

Brands like Mrs. Renfro’s and Old El Paso are regular customers, and Biad Chili is but one of the Las Cruces–based processors that supplies them. The Biad family has worked with NMSU since 1951 and today operates three dehydrating plants.

“The institute is always listening on how they can improve varieties, what the growers need, what the industry is looking for,” says Chris Biad, one of the family partners. “They would come up with different versions, we would produce them and see how they worked, then go back and say, ‘It’s great for consistency, but it doesn’t peel well,’ and they’d try again.”

When Paul Bosland proposed starting an institute, a wall of skepticism appeared. “People wondered if chile was a fad,” Bosland says. “One person said, ‘It’s nothing but a damned condiment.’ ” He moved forward, became its director, and grew into the king of capsaicin in part through his successful breeding of new varieties (more than 20 since 1988) and a talent for promoting New Mexico chile as star chefs turned spice into an epicurean craze.

In 1999, he won an Ig Nobel Prize from Annals of Improbable Research magazine for breeding NuMex Primavera, a jalapeño with all of the flavor and none of the heat—something salsa makers had requested, to replace the less flavorful bell peppers they were adding to their products. The feat drew comical jabs from those who thought the whole point of a jalapeño was its sear, but Bosland happily accepted the award. “It was good publicity,” he says. “I figured most people don’t even know New Mexico is a state.”

He went on to pioneer chiles with great flavor and heat, but also sprightly colored ornamentals that can be grown as houseplants.

Bosland retired last year, but not before helping to raise $1 million for the Paul W. Bosland Chile Pepper Breeding and Genetics Endowed Chair, ensuring that others continue his work for years to come. And what is to come? “For 30 years, I’ve been saying the ajís are next,” he says. “The ají amarillo is often used in ceviche, and it has a true South American flavor. We need a chef who sees it as the greatest thing, to create demand.”

Pumping out that and other varieties to feed the world’s zest for the latest zing is one of the success stories of his tenure. Here’s another: “When I started, Arizona and Texas were claiming everything,” he says. “Now we’re making New Mexico the center of the chile universe.”

Hot Spot

The Chile Pepper Institute Visitor Center & Gift Shop funds student research and jobs through sales of salsas, posters, T-shirts, and more, both online and at its campus store (currently closed for COVID-19). Gerald Thomas Hall, room 265, 945 College Ave., chile.nmsu.edu

The institute’s teaching garden, featuring 150 rotating varieties, is generally open to the public but is also closed for now; call or email to see if a socially distanced visit is possible. 140 W. University Ave., 575-646-3028, cpi@nmsu.edu

Read more from our "Ultimate Guide to New Mexico Chile"

The Mystery of Big Jim

A 10-year effort to restore one of New Mexico’s most distinctive chiles underscores how memory thrives in our taste buds.

José Gonzalez: The Allure of Chile Farming

Although he's tried other jobs, José Gonzalez keeps coming back to the farm where his family grows chiles, corn, beans and more.

The Ultimate New Mexico Chile Tasting Guide

We asked two experts to describe the flavors of New Mexico’s best chile varieties.

Matt Romero: The Chile Roaster

Rooted in family history, Matt Romero brings that heavenly scent and his special flair to the Santa Fe Farmers' Market.

More Than Just Salsa

Capsaicin does more than make chile hot, it is used in medicinal creams, bear repellent and in foods to give captive birds and fish a reddish hue.