AN INNOCENT CHILD, she wears a First Communion dress while performing with the Matachines dancers. Around the corner, she transforms into Eve, the progenitor of a new race of people. No, wait, she is La Llorona—wild, crazy, a killer. Or she is a buxom temptress, or a wily linguist and diplomat, or a trafficked woman doing what she must to survive.

More than anything, this centuries-old pasteboard of female identity prevails in Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche, an exhibit at the Albuquerque Museum through September 4. The show was previously at the Denver Art Museum but grows with a decided New Mexico influence in its Albuquerque iteration. Head curator Josie Lopez added new paintings, sculptures, and photographs, including a stunning altarpiece by Vicente Telles and Brandon Maldonado, and an entire section (with videos) that explores Malinche’s pint-size identity in the Matachines dances performed to this day in New Mexico’s Hispanic and Native communities.

Within the ongoing research, reassessment, and debate over the 16th-century Spanish conquest of Mexico, nearly every account takes note of a young woman (or girl) who used her skill with languages to salvage her situation by helping conquistador Hernán Cortés.

“It is a controversial story,” Lopez says. “She’s a young woman who was given into slavery by her family and then given to Cortés, along with 19 other girls. The exhibit explores the different ways identity has been placed upon her because there isn’t a historical record of her own experience. Different communities and people imbue her with different roles, and a lot of those relate to female identity.

“For me, a lot of the show gets at feminine identity in general. What are the roles we have been socialized as women to feel are part of our identity and how do we internalize those expectations?”

Jesús Helguera (Mexican, 1910–71) La Malinche, 1941. Photograph courtesy of Calendarios Landin.

Jesús Helguera (Mexican, 1910–71) La Malinche, 1941. Photograph courtesy of Calendarios Landin.

CORTÉS HAD TO SUBDUE and win the support of various Indigenous communities before taking on the Aztecan stronghold in 1519. In her years of servitude (which might have begun at age 12 or even earlier), Malinche picked up several languages, including Spanish, as she traveled with the conquistadors and their priests. That she helped hammer out the alliances needed to build an army big enough to take on the Aztecs and their leader, Moctezuma, has made malinchisto a contemporary term for “traitor” and malinche one for "slut" or “whore.”

Malinche eventually bore a son with Cortés, and later, a daughter with her Spanish lieutenant husband, before dying of unknown causes, possibly before hitting her 30th birthday. Those children (and others, borne by other women through consensual sex or rape) are regarded as the first mestizos, Spanish-Indigenous people.

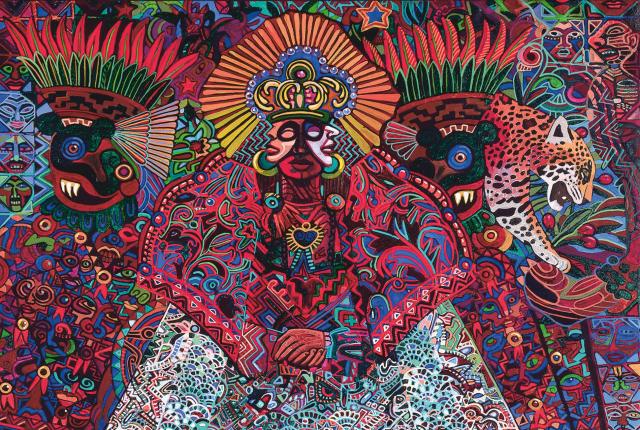

Maldonado and Telles’s altarpiece serves as a visual history lesson in five panels arrayed in three columns. Layering images of jaguar warriors and Aztec priests, Franciscan friars and the body of Christ with ones of both Spanish and Indigenous brutalities, the piece raises an essential question for Lopez: “Who is civilized and who are the savages?” she asks. “Throughout civilization, there is always violence.”

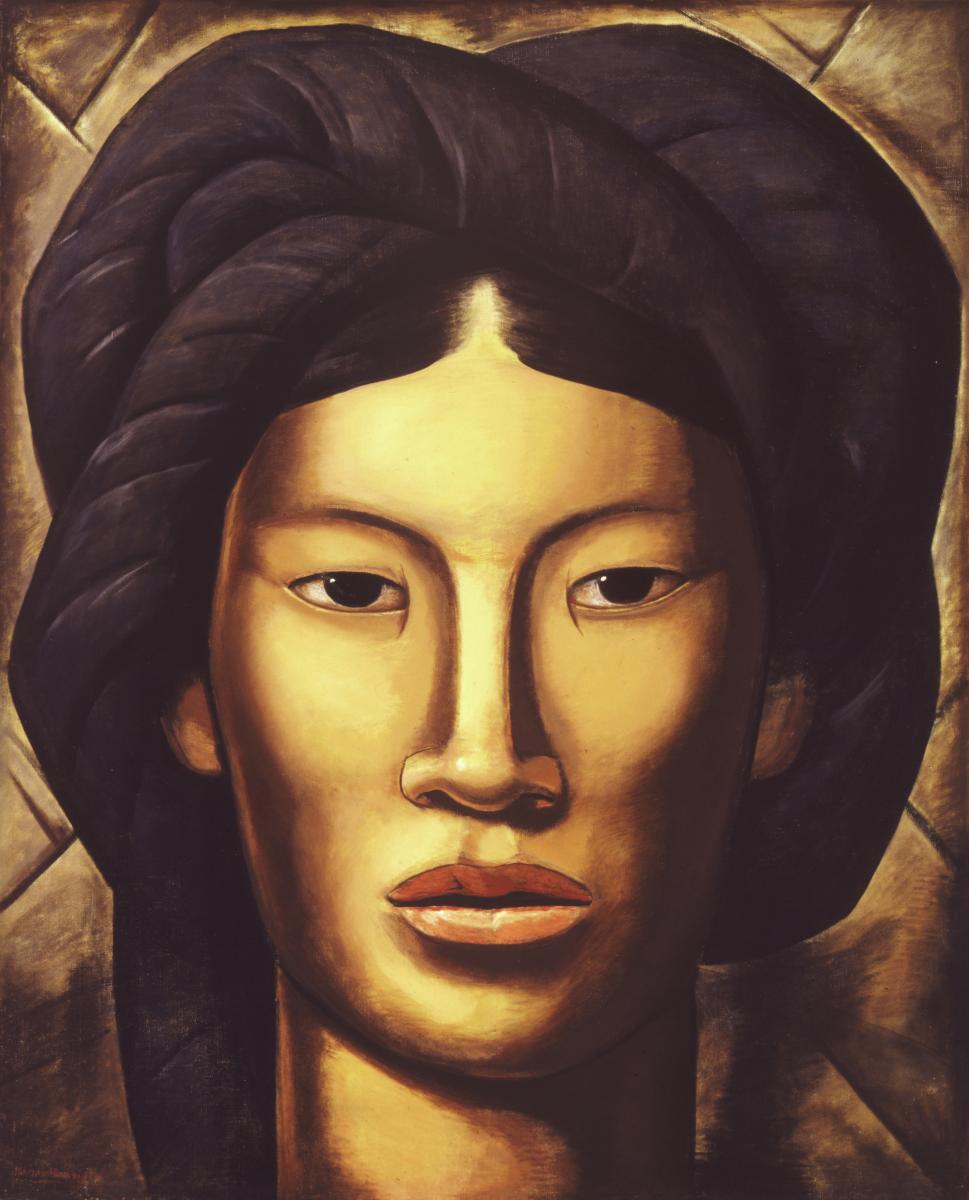

Alfredo Ramos Martínez, La Malinche (Young Girl of Yalala, Oaxaca), 1940. Photograph courtesy of the Alfredo Ramos Martínez Research Project, reproduced by permission.

Alfredo Ramos Martínez, La Malinche (Young Girl of Yalala, Oaxaca), 1940. Photograph courtesy of the Alfredo Ramos Martínez Research Project, reproduced by permission.

Malinche’s identity becomes a tool of violence as artists render her, in one case, as a light-skinned, barefoot maiden riding side-saddle in the lap of a movie-star-handsome conquistador and, later in the exhibit, as a vagina crafted with a hubcap, carved-wood heart, and circular saw blades (David Avalos’s Combination Platter #3: The Straight Razor Taco). Sandy Rodriguez’s Mapa for Malinche and Our Stolen Sisters, painted on the same amate paper used for the codices that serve as artifacts of the Spanish upheaval, places Malinche in the company of the 21st century’s missing and murdered Indigenous women. (Pay close attention to the artists’ genders when assessing their interpretations.)

The trademark image of the exhibit and its accompanying catalog, Alfredo Ramos Martínez’s La Malinche (Young Girl of Yalala, Oaxaca), presents only her face. And what a face. Beneath a Zapotec hairstyle, Malinche’s eyes and skin are clearly Indigenous. Those eyes gaze calmly and directly at the viewer, and her lips part slightly, as though she is about to speak. What might she say?

Perhaps she would tell a story of the 19 other girls awarded to Cortés. Who were they, what did they do, were they loved, and did they love? As Rodriguez notes in her artist statement for the Malinche map, “The fate of her sisters remains unknown.”

María Cristina Tavera (Mexican American, born 1965), La Malinche Conquistada, 2015. Photograph courtesy of María Cristina Tavera/Xavier Tavera.

María Cristina Tavera (Mexican American, born 1965), La Malinche Conquistada, 2015. Photograph courtesy of María Cristina Tavera/Xavier Tavera.

Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche is on exhibit until Sept. 4 at the Albuquerque Museum. The original exhibit, at the Denver Art Museum, was co-curated by Victoria I. Lyall, curator of the art of the ancient Americas at the Denver Art Museum, and independent curator Terezita Romo. The new version includes expansions by Albuquerque Museum head curator Josie Lopez. A catalog accompanying the exhibit is available in the museum gift shop. It includes essays and poetry, as well as images of the art. Think of it as an early Christmas present.