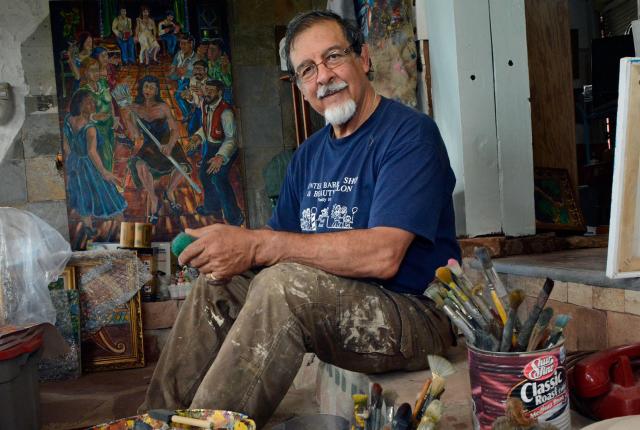

Above: Frederico Vigil in his home studio. Photograph courtesy of Jim Thompson/Albuquerque Journal/ZUMA Wire/Alamy Live News.

PERCHED ON A SCAFFOLD that hugs the walls of an Albuquerque Convention Center stairwell, Frederico Vigil stands on his tiptoes. Paintbrush at arm’s length, he sketches in yellow ocher the outline of a man carrying a wine barrel. He pivots to dip his paintbrush in the bucket, ducking under the scaffold. He’s 73 (“plus tax,” he adds), but his “fresco yoga” helps keep him limber, he says. “Are you afraid of heights?” he calls. “I am!”

Acrophobia aside, Vigil has spent nearly four decades clambering up and down scaffolds as one of the few masters of buon fresco (true fresco) in the Southwest—painters who work, Michelangelo-style, on just-applied wet plaster. His credits include North America’s largest concave fresco, also in Albuquerque, at the National Hispanic Cultural Center.

Since 2018 he’s been working on a 2,500-square-foot monumental fresco curving along the stairwell walls between the east and west complexes of the convention center, just outside the Kiva Auditorium. It tells the history of viticulture around the world and throughout New Mexico. It’s his latest masterwork in a storied career, and visitors can observe him at work into mid-2021, when he plans to complete the piece.

Art has long been a part of Vigil’s life, though not always in the traditional sense. He grew up on Santa Fe’s Canyon Road, before it grew into a famed stretch of fine-art galleries and working studios. Then, it was a rural, dirt road—“a wonderland,” Vigil says, recalling days of fishing in the Santa Fe River and playing in what became Patrick Smith Park. With five sons to keep in line, Vigil’s father put them to work building rock walls and helping the extended family mud their adobe houses, which would later reveal itself as Vigil’s start in fresco.

His formal apprenticeship, however, came in 1984. On a Santa Fe Arts Commission fellowship, he studied with Lucienne Bloch and Stephen Pope Dimitroff. The two had been apprentices of revered Mexican fresco artist Diego Rivera in the 1930s. Used by the ancient Romans and reaching its apex during the Italian Renaissance, fresco may seem an unusual choice for a present-day artist from Santa Fe. But Vigil found himself at home hauling and mixing bags of plaster. “I liked the building aspect of it. It’s very tactile.”

Above: Frederico Vigil’s fresco on the walls and ceiling of the torreón at the National Hispanic Cultural Center. Photograph courtesy of National Hispanic Cultural Center

Above: Frederico Vigil’s fresco on the walls and ceiling of the torreón at the National Hispanic Cultural Center. Photograph courtesy of National Hispanic Cultural Center

The art form has numerous points of resonance in New Mexico. Kiva paintings from the state’s Coronado Historic Site, in Bernalillo, regarded as some of the finest Pre-Columbian art in the United States, feature layer upon layer of paint on limestone, demonstrating Puebloans’ use of fresco secco, where paint is applied to dry plaster. (The original paintings were removed and are held in storage; WPA artist Ma Pe Wi, or Velino Shije Herrera, of Zia Pueblo, re-created them.)

Both Native American and Hispanic families have maintained their adobe homes through regular muddings to create long-lasting surfaces. Historically, people also often applied clay slips to their indoor walls. Called aliz, that plaster could be pigmented, just as is done in fresco.

Vigil’s technique of applying paint pigments to wet plaster is only the last step in a process that begins with two scratch coats of plaster. Once those dry, a third, smooth layer goes up. On that “sinopia” layer, a phase that Vigil plans to be working on through September, the artist sketches with a paintbrush, rendering his small paper studies at monumental scale.

“Sinopia is the most complicated. It’s how it’s going to look with perspective. I’m deciding what kinds of dynamics I want,” Vigil says. With these sketches complete, he traces full-scale cartoons, or preparatory drawings, of the images. Two more layers of plaster go up, covering his guides. During the final, smooth “intonaco” layer, Vigil applies only enough plaster to last for one session. Using the tracing paper, he pounces with charcoal or uses a thumbnail to set lines into the plaster.

Finally, he paints. As he applies his pigments, the water evaporates, creating a limestone rock laced with colors that are literally grounded in New Mexico. Vigil collects rocks from throughout the state—red from the Jemez Mountains, ocher from the mesas of Abiquiú—and grinds them with a mortar and pestle to make dry pigments that he mixes with water. New Mexico has all the colors, he says, save lapis, which he gets from Afghanistan.

“You only have so much dancing time,” he says of the painting phase. “The wall dictates how much you’re going to paint.” Ten to fifteen square feet can take just as many hours. He works section by section, the wall coming together a square at a time.

The art form is unforgiving. “Fresco does leave you naked. It exposes your inadequacies,” he says. He recalls painting the last piece of a fresco in Santa Fe’s Rosario Chapel.

“I blew it,” he says. “I was rushing, and I was arrogant. It doesn’t matter how small the area is. If you have a 2,000-piece puzzle and you don’t have the last piece right, you’ve ruined it.” The only way to fix a mistake? Let the plaster dry, scrape off the layer, and begin again. He feels the images in his mind—and in his body as the muscle memory learned through days of fresco yoga kicks in.

“I try to work on one image a day, then I can dream about the next image at night,” he says, closing his eyes as though already drifting away into a dreamscape where he can see the images taking shape. “Physically, I’m slowing down a bit,” he says with a sigh. “But some of it’s faster because of experience.”

Above: The convention center project includes preparatory drawings, scaffolds, and helping students with their works. Photographs by Lucy Stella Reyes.

Above: The convention center project includes preparatory drawings, scaffolds, and helping students with their works. Photographs by Lucy Stella Reyes.

That experience is immense. He’s painted 16 frescoes, in New Mexico and the Duke City’s sister city of Alburquerque, Spain. His smaller-scale, two-dimensional works have also been exhibited across the United States. His most notable work to date is Mundos de Mestizaje, inside the National Hispanic Cultural Center torreón. Completed in 2009, its 4,000 square feet soar up and curve around two-story-high walls and crawl across the ceiling. The project took seven years and several of Vigil’s toenails—he lost a few after days and months of gripping the scaffold with his toes.

Mundos de Mestizaje tells 3,000 years of Hispanic history. A scholar at heart, Vigil becomes a true student of his subject matter. For the convention center mural, he’s drawn from the full history of winemaking, depicting early wine vessels from the Egyptians, Romans, and Greeks along the bottom of the fresco. A quote from Louis Pasteur, who studied fermentation, ribbons through the vessels: “Wine is the most healthful and most hygienic of beverages.”

Below the landing between the first and second floors, Vigil traces the grape’s development from blossom to fruit. Sandía Peak wraps around the east wall, while the outline of the Organ Mountains rises on the west. The west side tells the story of the Spanish influence, while the east side depicts Native American agricultural techniques, such as waffle gardens and diversion dams. Since it’s painted in a stairwell, every step allows a different perspective, and new portions emerge from one landing to the next.

As he did while working on the torreón, Vigil brings in apprentices for this fresco. So far, he’s worked with nearly two dozen high school, university, and adult artists. They’ve helped with the larger project, as well as creating their own swatches of work on the walls of the studio turned mini fresco gallery on the ground floor of the convention center.

“Our hope is that as these previous and future teaching and learning opportunities expand, the very historic art form of fresco will live on, just as it has been passed on from artist to artist for centuries,” says Sherri Brueggemann, manager of the City of Albuquerque Public Art Urban Enhancement division. The city’s Public Art Program is funding the project, which involves an interactive digital story panel that Corrales-based digital exhibit company Ideum is creating.

“Albuquerque can become a mecca in fresco,” Vigil says. “It’s already indigenous. It’s already part of the fabric here. And the young people’s talent is incredible. I want to share what I know.”

And what does he know? “After all these years, I’ve finally learned how to erase,” Vigil confides. But after nearly 40 years of creating frescoes, his paintbrush rarely falters.

The Master at Work

Frederico Vigil works weekdays, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., at the Albuquerque Convention Center, 401 Second St. NW. Don’t hesitate to ask him questions. He’s glad to discuss the process. Both the ground floor and second floor have mini-exhibits of his drawings and preparatory sketches, which are interesting to compare to the work in progress.