Frank Turley in his studio at “the granddaddy of blacksmithing schools.”

Frank Turley in his studio at “the granddaddy of blacksmithing schools.”

BACK IN THE DAY, Frank Turley earned part-time cash by shoeing horses, so when he stumbled on a mysterious contraption in the Palace of the Governors’ storage basement, it seemed vaguely familiar. Four feet long and half as high, the mid-1700s artifact had two barrel-like pumps of rawhide attached to craggy boards.

“They were filled with dirt,” he recalls. “I cleaned it out, and inside I found an old, brittle piece of paper with old-fashioned handwriting that said ‘Sena Family Bellows.’”

Bingo! Santa Fe blacksmithing gold. The Sena dynasty began in 1693 with Bernardino de Sena outfitting Spanish colonists with pots, tools, and weapons. It ended in the 1920s when Abrán Sena turned out his last bit of forged steel.

Turley found his gem in the early 1970s, when blacksmithing was an all but dying art. A museum conservator, he also found centuries-old locks, keys, hinges, and lamps. Betting that others might want to re-create them, he opened a school in a corrugated metal building he rented for $20 a month. Today, he figures his Turley Forge Blacksmithing School (“the granddaddy of blacksmithing schools”) has trained 1,600 men and women, from backyard hobbyists to award-winning artists. Across three and a half decades, he’s also seen a lost art blossom into a New Mexico renaissance.

Centered on a pack of working blacksmiths off Santa Fe’s Siler Road, the wave has splashed into Taos, Tijeras, Albuquerque, and Las Cruces. There’s Tom Joyce, an internationally recognized artist and MacArthur Foundation fellow. Helmut Hillenkamp holds the highest prize given by the Artist-Blacksmith’s Association of North America and has pieces in Big Sur’s Esalen Institute and the Dakota, New York’s storied apartment building. Christina Sporrong melds blacksmithing with punk bravado to craft 26-foot-tall kinetic sculptures for festivals like Burning Man.

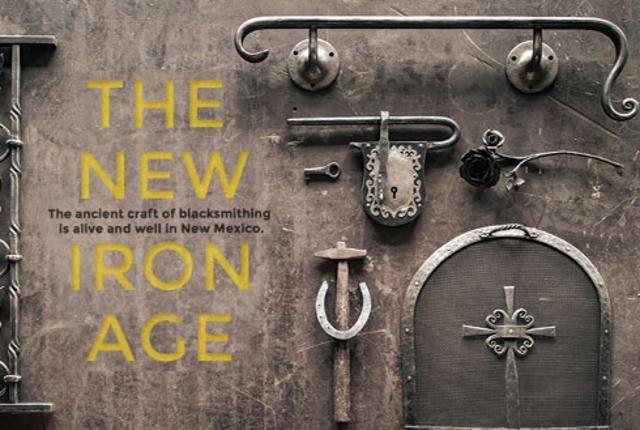

From barbecue tools to stair railings, fireplace screens, ornately topped chocolate pots, and scrap-metal barstools, a new kind of iron age has erupted in built-to-pound shops filled with smoke, sweat, and indomitable passion.

“I got a bad flu last winter and still had a cough months later,” master Spanish Colonial blacksmith Rene Zamora says in his Santa Fe smithy. “The doctor said, ‘Give up blacksmithing.’ I can’t do that. I’ll do this till I die.”

Soon after he opened his school, Turley moved out of that $20 building and into a onetime barn off West Alameda Street, a short walk down from the small house he shares with his wife, Juanita. Most of his classes span three weeks of seven-hour days. Up to five students go home with the most essential thing they’ll need to keep learning: made-by-hand hammers, tongs, and chisels.

He also covers ornamental scrollwork and architectural hardware, like door latches and hinges, the prized adornments to an authentic Santa Fe–style home. That said, Turley figures 97 percent of his students will never put in a day as a working blacksmith.

“Some of them, they don’t know what it’s really about, but it has a romantic aspect,” he says. “Or they want to make sharp pointy things—you know how men are. One of my students called me up recently, and I said, ‘Are you still blacksmithing?’ He said, ‘No, Frank. I’m a surgeon.’”

Despite his advancing years (he’s 80-ish) and a few health problems, Turley still takes the occasional job—like the 40-inch-long hinges he recently contributed to wood-carved gates in Ojo Caliente. He also dabbles in high fashion with his stepdaughter, nationally renowned Taos Pueblo designer Patricia Michaels, who uses his forge to craft metal-and-mica earrings and enlists Turley to make the frames for her water-lily parasols.

Within the blacksmithing community—an unusually collegial bunch—the benevolent Turley is regarded as a sort of Yoda. He’s exhibited his work in museums, writes articles for trade journals, and, with noted historian Marc Simmons, produced the 1980 book Southwestern Colonial Ironwork. A former Arthur Murray dance instructor, he does tai chi and qigong to counter the physical stress of pushing steel. Lately, he’s invited the assistance of Taylor Vallot, who helps with what Turley calls “the gorilla work”—heavy lifting and things like that.

Behind a wooden door garnished with test burns of cattle brands, students stand before waist-high forges fed by propane, learning to tend the optimal fire and read a metal’s heat by its color. One of the first things they’ll learn: Blacksmithing isn’t brute sport. You don’t pound a piece of steel as hard as you can. You move it like clay—rhythmically, judiciously, bit by bit—before yellow-orange fades to red and the metal goes back to the fire.

Blows go wild. Sparks sizzle skin. It takes a tough-love kind of mentoring, which Juanita says she sometimes hears from inside the house.

“I cuss at all of them,” Turley says.

Rene Zamora specializes in Spanish Colonial designs.

Zamora signed up for the classes in 1997 after years of working as a contractor on other people’s homes. When it came time to build his own, he couldn’t afford the Spanish Colonial–style hardware he desired, so he learned to make it. Within a few years, enough clients wanted his latches, locks, and keys that he surrendered his contractor’s license and went full-bore into blacksmithing. In 2002, he won his first Spanish Market award, and he’s brought home ribbons nearly every year since.

He tops potter Camilla Trujillo’s chocolateras with minutely detailed lids and locks. Using wood salvaged from Rosario Chapel, he crafts furniture bearing original nails, hinges, and hasps. Each piece can consume days of close-focus work, requiring both a Zen attitude and iron will.

“To learn this craft,” Zamora says, “to become proficient at it, takes a lot of diligence, but also stubbornness. You have to be more stubborn than the iron.”

The weekday is done for office workers, but Helmut Hillenkamp’s Iron to Live With smithy is still churning heat as he and fellow blacksmith Mark Miller toil into the evening. You can likely hear them from Santa Fe’s nearby Cerrillos Road. Hillenkamp swings at a rod curled around his anvil’s tip, each heat-and-hit cycle bringing it closer to his planned bell holder. Miller uses the pneumatic hammer to bang-bang-bang steel bars into gently twisting fence posts that evoke an aspen forest.

A native of Germany who sports an anvil-shaped earring, Hillenkamp came to Santa Fe in the early 1990s to study with Tom Joyce, who was then establishing a new standard of excellence for modern blacksmithing. Like a lot of Joyce’s students, he eventually opened his own shop, where he now helps new practitioners sharpen their skills before striking out on their own. That mentoring process, at work in shops throughout the state, plays into a three-part symbiosis. The spirit of shared knowledge ensures the art won’t get lost again. The relative affluence of Santa Fe homeowners supplies enough work for masters and emerging artists. And the dry desert air guarantees the work acquires only enough rust to contribute a pleasing patina.

Miller fits a common profile: Years ago, his wife gifted him with a blacksmithing class, but offspring and a suit-and-tie career diverted him. Recently retired, he decided to again embrace smoke and hammers. In doing so, he joined a roster that gleams with Santa Fe smithing standouts, including John Prosser, Shehan Prull, Caleb Smith, Peter Joseph, and Christopher Johnson.

“You would be hard-pressed to find this many people in another city doing blacksmithing,” Hillenkamp says. “Maybe Seattle or San Francisco, but they have millions of people.”

With his wife, ceramist Christy Hengst, Hillenkamp has built bus shelters in Santa Fe that combine iron shade with mosaic beauty. His bread and butter, though, comes from residential work, including a bird-of-paradise stair railing for an apartment in New York City's Dakota. One of his Santa Fe fences crawls with vining roses that look almost paper-thin.

“For me,” he says, “this is about fun. This is my gym. This is my social place. It’s where I make a living and where I enjoy myself. I like to figure things out and fix things. To be a handyman is not creative enough. To be a sculptor is not useful enough. To be a mechanical engineer is to be a head with no body. I need the physical, too. Blacksmithing is a good combination.”

A gear-grinding four-wheel-drive through the foothills north of Madrid leads to Christin Boyd’s off-the-grid Flygirl Iron shop. Cobbled together from found materials and thrifty purchases from fellow smiths, it perches on a foothill and gazes onto the Ortiz Mountains. “I worked in clay for about 12 years, but I tend to drop and break things, so I needed a sturdier medium,” she says. “I started working with metal, and it was an intimidating place to go—very male.”

She took one of Turley’s classes, then apprenticed with Hillenkamp while finding her groove with whimsical gates and railings, including the one in front of Madrid’s Art Shack. Composed of rusty rebar she scrounged throughout the old mining town, its bars still boast their industrial roots, but the tops twirl into fiddlehead ferns.

“Every job is a challenge,” she says. “I’m always a little scared. You misstep, and you cost yourself so much time. There’s a lot of strength involved, but it’s endurance strength—hold a hammer and use it for hours. Many times, you’re hitting very softly. It’s about finesse.”

Christina Sporrong followed a similar path in Taos, graduating from welding to blacksmithing in the early 1990s. After years of making architectural ironwork, she jumped into kinetic sculptures, one of which, a towering heron, is at the Taos Mesa Brewery. For years, she’s helped other women beat the men’s-club stereotype through Women’s Welding Workshops.

“Sometimes it’s a life-changing experience to overcome some of the fears they walk in with,” she says.

The latest works out of her Spitfire Forge combine enough techniques (welding, sculpture, the kinetic arts) to qualify for a new kind of art medium—which would suit her fine.

“I love the new direction of blacksmithing, which inevitably is rooted in the craft itself, but has branched out, absorbing all kinds of newer technologies,” she says.

The master of that transformation is Joyce, who divides his time between Santa Fe and Belgium. His work long ago left traditional blacksmithing, moving into a gamut of iron expressionism, including massive sculptures, mixed media, and, at the 9/11 Memorial Museum, letters—forged from 8,000 pounds of World Trade Center steel—that spell out a quote from Virgil’s Aeneid: NO DAY SHALL ERASE YOU FROM THE MEMORY OF TIME.

In 2003, Joyce became a MacArthur fellow, which comes with the right to call yourself a genius, though he never does. Still, other blacksmiths speak his name with a mixture of personal fondness and the professional respect owed to someone who celebrates his ancient art in a futuristic way.

In Hillenkamp’s office, a decrepit bellows hangs next to samples of his own modernistic efforts—an example of the easy grace that lies between past and present in an endeavor once nearly lost to time.

“I ask myself, ‘Is it creative? Is it fun?’ ” Hillenkamp says. “But in the long run, I like to take some responsibility for carrying on the craft.”

Helmut Hillenkamp outside his studio in Santa Fe.

BLACKSMITHS IN ACTION

CASA SAN YSIDRO in Corrales holds a large collection of Spanish Colonial ironwork and sells modern versions in its gift shop. Blacksmith Dave Sabo demonstrates the craft during special events. Open February through November; (505) 897-8828; mynm.us/sanysidronm

Las Cruces’ FARM & RANCH HERITAGE MUSEUM offers week-end blacksmithing demos throughout the year, as well as workshops. (575) 522-4100; nmfarmandranchheritagemuseum.org

Helmut Hillenkamp’s IRON TO LIVE WITH studio in Santa Fe offers summer workshops. iron-to-live-with.com

Monthly meetings of THE NEW MEXICO ARTIST BLACKSMITH ASSOCIATION are open to anyone. Members also give demonstrations at the Rio Grande Valley Celtic Festival and the State Fair in Albuquerque—good places to purchase barbecue tools, artwork, and more. (505) 280-2167; nm-artist-blacksmiths.org

Near Santa Fe, EL RANCHO DE LAS GOLONDRINAS has blacksmithing demonstrations during special events. Open June into October; (505) 471-2261; golondrinas.org

The TURLEY FORGE AND BLACKSMITHING SCHOOL in Santa Fe holds three-week courses for aspiring blacksmiths. (505) 471-8608; turleyforge.com

THE SANTA FE BOTANICAL GARDEN currently features Bloom, six sculptures by Tom Joyce that will be officially unveiled this spring. (505) 471-9103; santafebotanicalgarden.org

THE TOOLBOX, a new Taos makerspace, will be offering classes this winter, including welding and blacksmithing, taught by Christina Sporrong. thetoolboxtaos.org

Want more like this? Subscribe now!