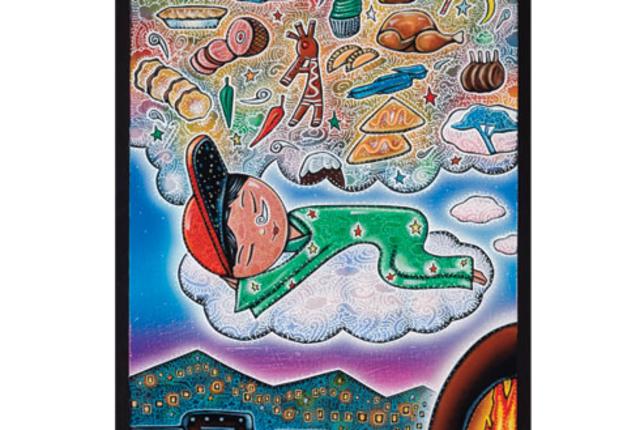

Above illustration by Joel Nakamura

I’ve spent a good chunk of my life in stinking cities, which sounds redundant—what urban area doesn’t have a little funk to it? To recall my stay in Brooklyn is to summon the smell of garbage: heaped in bags and dumpsters in the summer heat, stewing in fetid puddles on the A-train tracks. In Ciudad Juárez, where I lived for a couple of years, a walk through neighborhoods fouled by sewage and bus exhaust made the first whiff of masa from a tortillería that much more intoxicating. After a while you don’t think of certain smells as bad; they’re just part of a place’s sensory signature, reminding you as you wake up exactly where on earth you are.

It was exotic and a little unsettling, then, to move last summer into an apartment on Canyon Road that faced a large garden. There was no putrid undertone to balance the scent, the way perfumers use civet or ambergris; no puddles of motor oil or black trash bags spilling their guts on the street corner; only clean mountain air. My first week in Santa Fe, I explored the east side of town with my mom, who had helped me move. “Oh, that smells lovely,” she would remark as we passed sidewalk beds of lavender and Russian sage. Then, half a block later: “Isn’t that just heavenly?”

“Okay, Mom, new rule,” I finally said. “Let’s only point out when we smell something bad.”

For the rest of the week we walked the city in pleasant silence.

Ask people what reminds them of New Mexico and chances are they’ll name a smell. Roasted chiles. Desert rain. Piñon smoke. To folks who have a history with the state, these are Proustian madeleines, prone to yank them by the nose into the past, which, neurologically speaking, is no accident. Olfaction commands a full percentile of the human genome and is especially good at inducing vivid emotional recall. Researchers chalk this trick up to the shortcut from the nasal cavity to the amygdala and hippocampus, brain regions involved in memory. “Smells detonate softly in our memories like poignant land mines, hidden under the weedy mass of many years and experiences,” the author Diane Ackerman once wrote. We may think in words and pictures, but our hearts leap at smells we sometimes can’t even put our finger on.

For me, the state’s essence has always been in the soil. I think of the pale dust at Ghost Ranch, where I took summer vacations as a kid, and how it smelled on my skin and in my sweaty sneakers after days of off-trail exploring. The cabins we stayed in were built on parched earth that came alive during July thunderstorms, singing with strange, sweet minerals. Petrichor, the odor is called: divine blood from the rock. It haunted me for years.

At El Zaguán, the historic Canyon Road artists’ residency I had moved into, New Mexico dirt was literally baked into the walls. When dry, the adobe gave off only a faint must, but as the rains picked up it became possible to pick out the straw and sediment in the brick, the damp soot in my fireplace, the rich decay of the old wooden gate. Thunderheads formed over the mountains, and you could smell them from miles away, stirring up a hint of old nickels—that petrichor I’d missed, a land mine detonating softly—as they swept down forested slopes and darkened the garden outside my window. Hollyhocks and roses and dozens of flowering herbs I can’t name drank in the afternoon showers and at dusk gave back a bouquet that made tourists passing by the white picket fence stop in their tracks. By late summer the apple trees behind the house had fruited, and the sour green flesh served as a reminder that taste, too, owes much of its power to scent.

When I sorted through the glut of sensory data, however, what struck me were the omissions. It wasn’t just that Santa Fe didn’t have the litter and industrial pollution I’d grown oddly attached to. Familiar domestic smells were missing, too. The metallic tang of air-conditioning I’d grown up with in Texas was absent, as were the traces of cleaning chemicals and food scraps and gym clothes, all whisked away on the breeze through my open windows. I was surprised to discover that I missed them. That first summer, I’d hang my sheets out in the morning and find by the time I came home from work that they’d gone through another rinse cycle in the rain. This routine made scented detergent a waste of money, but it entertained a fellow resident, Max Carlos-Martinez, who liked to count the number of days my laundry stayed up on the clothesline trying to dry.

Max was a prodigal son of New Mexico, home after a couple of decades of painting in New York. As we got to know each other, I’d often wander down the breezeway to his apartment, hoping to catch the aroma of red chile enchiladas in the oven. What I really liked, though, was the stench of the living room where he worked. Evil-smelling acrylics. Cheap Scotch. An ashtray overflowing with American Spirits. It was like encountering the ghost of an older, livelier Canyon Road, or the house parties I’d left behind in Juárez. I gulped the impure air down. This, various brain regions insisted, was more like it.

I slept in a few Saturdays and missed the chile roasters in grocery store parking lots. Instead I experienced fall as a creep of color. The leaves of the burly old horse chestnut outside my window rusted and curled at the edges and finally sloughed off. One by one, the herbs in the garden went dormant, subtracting their fragrance from the chilly air. In the end only the evergreens in the hills were left, and I came to think of these as the true smell of Santa Fe, sweet and mysterious and dry. At night the streets filled with their ethereal woodsmoke, like the incense from a priest’s censer. The city went still. Frost arrived.

Bonfires and farolitos light Canyon Road and tinge the air with the wintry smell of smoke.

Photo by Charles Mann

In late December, Max knocked on my door: It was time to make farolitos. We spent the last indigo hour of daylight lining the garden and adobe walls with candlelit paper bags that, thanks to my stiff fingers, got a few holes burned in them. The Christmas party that night was at Max’s place. I mulled wine on the stovetop with clove and cinnamon while he tended a pot of chili and set out biscochitos whose floury sweetness benefited from the dark whisper of anise. The apartment thickened with cigarette smoke and strangers’ perfume, and I wondered which of these smells might remind Max of some family holiday in a long-ago Albuquerque. It wasn’t until much later that I realized my first Christmas in New Mexico had been free of wreaths or peppermint, and I was glad for it.

A few at a time, partygoers warmed their hands over a fire in the yard and slipped out into the street to join the caroling crowds. Near midnight Max and I followed, laughing and dizzy. Canyon Road was a tunnel of candle flame and wick smoke. The flow of families slowed and eddied around bonfires where piñon logs crackled and folk musicians sang. Teenagers ran down the street arm in arm, giddy at the closeness of each other’s bodies. And then, suddenly, it was calm. Up where the galleries gave out, the farolitos did too. Nothing lay beyond but negative shapes of mountains and the keen, aching smell of snow gathering overhead. I lingered for a second, wondering at this strange city—fine, Mom, it was lovely; it really was heavenly—and then I found Max’s silhouette and we followed our noses down the hill for home. ✜

—John Muller