NEED TO KNOW

This year’s Madrid Christmas parade begins at 4 p.m. on Saturday, Dec. 5. The town’s holiday light displays kick off that night. Visit during the first three weekends of December to see the lights, enjoy extended hours at shops and galleries (most are open until at least 7 p.m.), and catch live music at the Mine Shaft Tavern on Fridays from 5 p.m. to midnight, Saturdays 3 to 11 p.m., and Sundays 4 to 8 p.m. (505-473-0743; themineshafttavern. com). Rooms are available for rent through the Mine Shaft or via Airbnb.com. For more information on Madrid, visit turquoisetrail.org and visitmadridnm.com.

AFTER THE OLD MEN in kilts start their bagpipes wailing, after the guy dressed as a Christmas tree is pursued by dancing girls with chain saws, after a whole motorcade of Santas riding in sidecars and Model A Fords and synthesizer-equipped trailer floats has paraded down the hill, that’s when it will be Solo the Christmas Yak’s time to shine. The bulky Himalayan ox will come galumphing into town the way he does every year, a red reindeer nose strapped across his broad gray snout. On his back, five-year-old Maizie Kostrubala will grip a handful of fur and beam cherubically at the crowd, who’ll wave back at her and turn to angle themselves for yak selfies. The Madrid Christmas parade will be another rousing success.

That’s the plan, anyway.

But something is wrong: Solo does not galumph. He ambles a few yards from the starting line and comes to a halt, his brown eyes blinking in the sun. A line of strangers stares up the two-lane state highway with phones held high. Sunglassed dads shouldering toddlers crane to see what’s holding up Christmas. As the music up ahead grows faint, Solo shyly lowers his horns and studies the macadam.

ity the yak who doesn’t know his Madrid history. You can almost see him puzzling over how this village just a shout from his Cerrillos pasture got so popular with eggnog-enthused weirdos. He has no clue that the surrounding Ortiz Mountains remain plump as a naughty child’s stocking with coal—more than 50 million tons of soft bituminous and hard-to-find anthracite, enough that a mining community sprang up here around the turn of the 20th century. The name Oscar Huber means nothing to his fuzzy yak’s ear, though as superintendent, Huber oversaw Madrid’s heyday as a company town that boasted its very own moving picture show and more automobiles than anywhere else in the state, every one of them a Chrysler bought from his son Joe’s dealership.

It was Huber who guessed that doing laps on Madrid’s lone drag might not keep the miners entertained for long, and in the thirties threw the company’s resources behind a holiday celebration so over-the-top—50,000 lights powered at company expense; a radiant Toyland populated with fairy-tale characters and Mickey Mouse; and, on the bluff overlooking town, a full-scale New Mexican Nativity, Bethlehem rebuilt in wood and adobe—that Continental Airlines used to reroute its December flights just to give passengers a peek. It was Huber who once toured this magical yuletide kingdom with Walt Disney himself, giving rise to the local suspicion that Disneyland is a mere Madrid ripoff. And it was Huber who kept the lights on at the Mine Shaft Tavern to the lonesome end, after operations shut down and the miners took off, abandoning the town to a quarter-century of ghostdom.

But maybe I’m being too hard on Solo the Christmas Yak. The truth is, I didn’t know most of this myself until an hour or two before the parade, when I nipped into the resuscitated Mine Shaft for a drink.

eaven is literally right up here at the bend,” Lori Lindsey says. For a second her directions sound like Madrid metaphysics, betraying a kind of cosmic optimism that’s as good an explanation as any for the town’s miraculous renaissance a few decades back.

eaven is literally right up here at the bend,” Lori Lindsey says. For a second her directions sound like Madrid metaphysics, betraying a kind of cosmic optimism that’s as good an explanation as any for the town’s miraculous renaissance a few decades back.

As the proprietor of the Mine Shaft, Lindsey is also an unofficial ambassador, welcoming tourists and clueless reporters along with her regulars. Before I’ve slurped the foam off a pint of velvety red ale, she’s already filled me in on this place folks still sometimes call Christmas City, rattled off a list of local acquaintances to make, and somehow gotten me and Amiel, the photographer on this assignment, appointed to judge the town’s light displays, which officially plug in tonight. To confirm our duties, we’re supposed to check in with Linda Dunnill over at Heaven, a boutique just a few doors down. Oh, and if we want to learn more about the town, we ought to stop by and see Diana Johnson.

The Johnsons of Madrid gallery is housed in Joe Huber’s old car dealership toward the south end of Main Street, which is really just a few hundred yards’ worth of NM 14. The building was left like all the rest to rats and stray dogs as first Oscar and then Joe tried for decades to sell off a derelict town with a “fine industrial location.” Finally, in the early seventies, Joe split Madrid into lots and unloaded them on the only interested buyers, countercultural types looking for a cheap place to get off the grid and out of touch with the law. Among the first to move in were the Ducks, a small commune from Haight-Ashbury. They spent a year clearing their yard of coal so they could grow vegetables and other, less licit crops; only later did it occur to someone they might use the coal to stay warm in the winter.

Diana Johnson arrived early in the new wave of Madroids and knows local history about as well as anyone. She rummages in her files for a Collier’s article from 1940, back when the Christmas festivities drew national attention. “Everything is free,” the reporter marveled, “there never has been a hint of commercialism.” Johnson’s generation, trying to eke out a living, gradually embraced the touristic possibilities of a Madrid Christmas revival, but the idealism never left. As her son Eirik put it to the Madrid Artist Quarterly, the town’s whole existence is like Santa Claus, an impossibility propped up by belief and goodwill. “I don’t like to think of Madrid as a town full of hippies,” Diana says. “It was a bunch of independent thinkers who were going to change the world.”

Robert Shlaer, semi-cranky bagpiper.

On our way out the door, Amiel and I bump into Robert Shlaer, who’s wearing a kilt in early December. He explains that he’s a member of the Order of the Thistle Pipes & Drums, a Santa Fe bagpipe outfit. “Normally we wear Santa hats for this, and I just hate Santa hats. We play ‘Jingle Bells,’ and I just hate ‘Jingle Bells,’” he says. Then again, it’s possible he’ll be the lone piper to muster for the parade and can play whatever he wants.

“It’s meeting time and I’m the only one here,” he says. “With the weather, I should have checked my email before I came. But being a chronic optimist, here I am.”

![]() t’s true, the clouds are starting to look a little sketchy. Wind rattles the leafless branches along Main Street and keeps jackets buttoned to the top over on the Mine Shaft patio, where a crowd is gathering for the parade. Cars pull into town from Albuquerque and Santa Fe, each less than an hour away via the meandering Turquoise Trail.

t’s true, the clouds are starting to look a little sketchy. Wind rattles the leafless branches along Main Street and keeps jackets buttoned to the top over on the Mine Shaft patio, where a crowd is gathering for the parade. Cars pull into town from Albuquerque and Santa Fe, each less than an hour away via the meandering Turquoise Trail.

Les Reasonover, sixties-style Santa.

On the street, a Santa with John Lennon sunglasses and a penchant for flashing peace signs spots Amiel and makes a beeline to offer her a candy cane. “Now, before I can give this to you,” he says, “I’m required by municipal ordinance to ask: Have you been both naughty and nice this year?”

Amiel gets her candy cane.

With Santa as our guide, we find our way to Heaven, where a couple of angels are sharing a flask. (“Madrid doesn’t have a town drunk,” the saying goes. “We all take turns.”) The one busy affixing purple butterfly wings to her cowgirl getup is Jeanette Williams, a young, ruddy-cheeked bundle of cheer who used to have a gallery on Canyon Road and now works out of her studio near the Johnsons’ place. This is Madrid’s latest identity, as a laid-back, affordable annex to the Santa Fe art scene, filled out with funky little shops. While we wait for Linda Dunnill to put the finishing touches on her costume, I scope out the racks of frilly blouses and shelves where ceramic angels flit around the heads of sleepy-eyed Buddhas.

As it turns out, Linda doesn’t know much about judging the Christmas-light competition; neither will any of the other residents we’re referred to in turn, which offers a lesson in how Madrid feels about competition and possibly organization in general. She does, however, know Santa, whose real name is Les Reasonover. Before heading to the parade, they stop to pose for a photo, and just as the shutter clicks he leans over to sneak a neighborly kiss.

Maizie Kostrubala atop Solo the Christmas Yak.

![]() olo won’t budge. He is deaf to your entreaties, unmoved by your holiday traditions. To her credit, Maizie Kostrubala is handling the unplanned stop with aplomb; from atop her mount she smiles and waves graciously, the way princesses do. Behind her, Annie Whitney, Solo’s owner, sweeps her arm in big, cartoonish arcs that come to land gently on the animal’s matted rump. She grins and hollers, “That’s a bovine for ya!”

olo won’t budge. He is deaf to your entreaties, unmoved by your holiday traditions. To her credit, Maizie Kostrubala is handling the unplanned stop with aplomb; from atop her mount she smiles and waves graciously, the way princesses do. Behind her, Annie Whitney, Solo’s owner, sweeps her arm in big, cartoonish arcs that come to land gently on the animal’s matted rump. She grins and hollers, “That’s a bovine for ya!”

The front half of the parade is picking up steam now, ignorant of the yak traffic jam in the rear. There’s Robert Shlaer, marching alongside his Order, his hearing aid “set to bagpipe.” As he feared, several of his companions showed up in Santa hats, as did pretty much everyone else: the Harley-riding woman in a snow leopard jacket; the folks trotting behind costumed dogs; the volunteer firefighters in the town fire truck; and Les, whom Linda is gleefully spanking with a sheaf of sage. A young boy beside me turns to his parents in wonder: “How many Santas are there?”

And then, out of the corner of my eye, I spy one more Saint Nick coming up from behind, a snowy-bearded vision in red velvet, leading on a rope none other than Solo the Christmas Yak himself. The parade is on! Cameras flash. A cheer goes up. Maizie smiles triumphantly as her golden curls swing and bounce on the slow ride to the finish line. Madrid Christmas is saved.

he whole thing is over before you know it. Once you get up around the Old Boarding House Mercantile, the parade sort of peters out, veering off into a gravel parking lot where people are laughing and the chain-saw-wielding girls are getting down to “Dancing Queen.” You’ve all gone half a mile, tops.

he whole thing is over before you know it. Once you get up around the Old Boarding House Mercantile, the parade sort of peters out, veering off into a gravel parking lot where people are laughing and the chain-saw-wielding girls are getting down to “Dancing Queen.” You’ve all gone half a mile, tops.

Oma and Princess Esmeralda.

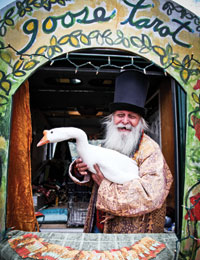

Some of the folks from out of town will stay to see the lights—which are worth it, by the way—and some won’t. Many experiences are still around the bend, not far from Heaven. You’ll sip cider and check out some art as one after another friendly gallerist tells you your guess is as good as theirs on the light contest. You’ll have your fortune told by a goose named Princess Esmeralda. You’ll do tequila shots with angels and watch what looks to be the whole town dancing with abandon at the Mine Shaft.

Maybe that’s where everybody is when your solemn duties as judge take you off Main Street and up a quiet, muddy dirt road to visit a church lit with farolitos. From here, the glittering Christmas strip feels impossibly far away. Low clouds block the stars. You’ll see an airplane duck beneath them, its red and white lights winking, and just then you’ll wonder how it all looks to the passengers peering down. ✜

—John Muller