EVEN NOW, stands of cottonwood, willow, and mesquite marking the course of the Pecos River offer but a tangle of weedy limbs. Around the onetime military post of Fort Sumner, on New Mexico’s eastern plains, the bosque has had more than a century to grow taller and thicker than it has. Stand here, in the timeless hush, and you can sense history’s heavy weight. The vast sky promises resilience, freedom, and home. But the stark land bears witness to a bleaker past.

On this ground on June 1, 1868, General William T. Sherman and 29 Navajo leaders negotiated an agreement to end one of the darkest chapters in the American story. At the then-40-square-mile expanse known today as Fort Sumner Historic Site/Bosque Redondo Memorial, the Navajos left their X marks on a document outlining a host of requirements in return for the right to go home. Hundreds of miles from this barren place stood four mountains, in New Mexico, Arizona, and Colorado—the boundaries of a sacred space within which Navajo people believed they were always meant to live. From late 1863 to 1868, they instead endured a dislocation bred by the zeal of Manifest Destiny.

From the day that they began their Long Walk home, the Navajos, or Diné, rarely spoke of Hwéeldi, their name for “the suffering place.” Never go there, children were warned. But as their defining treaty reaches its 150th anniversary, stances are shifting. Fort Sumner and Window Rock, Arizona, capital of the Navajo Nation, will host commemorative events. The state-owned historic site plans new exhibits using the voices of those who were imprisoned—Navajos and Mescalero Apaches—rather than those of curators and historians. As museums and historic places around the world similarly retool their explorations of divisive histories, Bosque Redondo prepares to become a place of inclusion, one with, perhaps, the power to heal.

“There’s a lot of hurt, a lot of resentment, especially among our elders,” says Jonathan Nez, vice president of the Navajo Nation. “A lot say maybe it isn’t time to talk about it. Others say maybe it is. It’s a delicate line for us to walk. But it’s important that, for our way of life to continue, for our language to continue, we need to have a frank discussion about what we went through there. It’s time for us to work together.”

IN THE 19TH CENTURY, as U.S. leaders asserted control over the American West, clashes erupted. New Mexico’s tribal peoples had long weathered times of trouble and peace with Spanish colonists. Now disorder reigned. The resulting years of land grabs, raids and counterraids, massacres, broken treaties, and slave trading have fed—and continue to feed—a library’s worth of research. Into this milieu stepped General James H. Carleton, armed with a national mission to subdue the Mescalero and Navajo peoples. In 1862, he ordered Colonel Christopher “Kit” Carson to kill all Mescalero men and move the women and children to Bosque Redondo—a new reservation that others had warned could not sustain crops and was far too remote. Carson instead persuaded Mescalero leader Cadete to surrender and, with more than 400 of his people, leave the Sierra Blanca Mountains, near today’s Ruidoso. In January 1863, they stepped onto land long claimed by Comanche and Kiowa peoples at Fort Sumner, a set-up too new and too ill-prepared to feed or house them.

Six months later, Carleton ordered Carson to attack the Navajos in today’s Four Corners region. The campaign led to a scorched-earth siege across the winter of 1863–1864, during which starvation became a tool of war. Bands of Navajos, weak and ill, started surrendering in 1863. By 1866, around 9,000 people had endured the Long Walk to Bosque Redondo. Unknown others remained in hiding. The 53 forced marches over three years, as the Diné surrendered or were captured, have been called New Mexico’s Trail of Tears, echoing the relocation of southeastern tribes in the 1830s. At least 500 Navajos died en route. They could lose all their supplies crossing the treacherous Río Grande. Some people drowned. Elderly people or pregnant women who couldn’t keep up were shot. They walked in high heat. They walked in snowstorms, struggling to keep their horses and sheep alive. They didn’t know how to prepare the rations of unfamiliar foods—flour, bacon, and coffee—so ate them raw, then fell ill. The soldiers vowed that better conditions lay ahead. And so they walked.

At Fort Sumner, they were met by the Mescalero, a tribe they had long warred against. With the nation consumed by the Civil War, supplies came rarely. Food turned rancid. Tribal men built housing for the military, even as their own families lived in tattered tepees or holes in the ground.

The water of the Pecos proved too alkaline for drinking, and the river flooded regularly. Cutworms destroyed crops. Firewood lay miles away. Other tribes raided them. At one point, more than 10,000 Native people, soldiers, and military families crowded onto the reservation, making it the most populated place in the New Mexico Territory. (Fewer than 2,000 people live in all of DeBaca County today.)

On November 3, 1865, the Mescaleros slipped away in the night, melting into the mountains, joining Comanches, heading south to Mexico, and continuing their war against the United States until President Grant established a reservation on Sierra Blanca in 1873. (Other bands of Apaches fought on. In 1886, Geronimo and his Chiricahua holdouts surrendered, then endured 27 years of captivity in Oklahoma.)

The Navajos languished at Bosque Redondo, too ill to risk a months-long escape through hostile communities. Up to 1,500 of them eventually lay in unmarked graves. U.S. leaders fumed at the million-dollar annual cost. Carleton lost his command in 1866, after which legendary warrior Manuelito and two dozen of his emaciated followers finally surrendered. In 1868, the Navajos refused to plant crops. They had given up. They stood in lines awaiting rations. The reservation had failed.

Sherman hoped to work out a treaty that would send the Navajos to the Oklahoma Territory. Barboncito, elected by Manuelito and other Diné leaders to bargain for their side, stood firm on a return to the land they loved. The men agreed to 20 pages of concessions, including that the Navajos would send their children to U.S. schools, speak English, allow a railroad through their land—they would, in short, assimilate to the American way of life. Given all they had been through, Barboncito said, it was worth it. According to historical accounts, he told his people, “After we get back to our country, it will brighten up again, and the Navajos will be as happy as the land. Black clouds will rise, and there will be plenty of rain.”

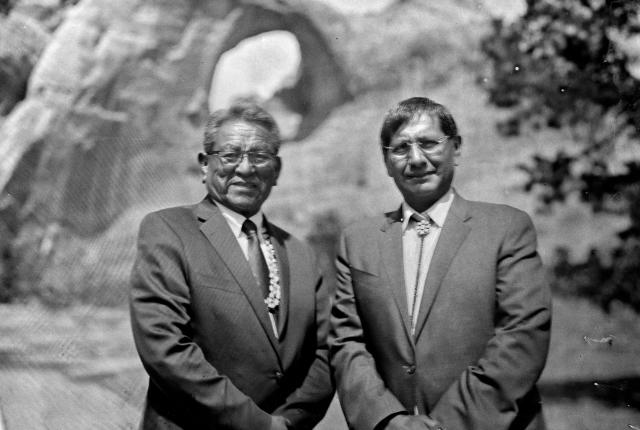

MORNING SUN WARMS THE SHEER red-cliff backdrop of the Navajo Nation Museum, in Window Rock, as tribal members filter in for an important meeting. On this day, in the late winter of 2018, President Russell Begaye, Vice President Nez, and other officials will sign a proclamation declaring 12 months of treaty commemorations and promise to fund the delivery of the original treaty from the National Archives for a month of public viewings and events.

Surrounding them are 27,000 square miles of Diné land, far more than the 5,200 square miles granted in the treaty. More than 350,000 people claim Navajo affiliation. Navajo weavers and silversmiths rank among the world’s best. A massive agricultural enterprise and extensive mineral resources support the tribe’s economy. Yet poverty gnaws at its people, along with environmental challenges, encroachments on sacred places, and the erosion of traditional ways.

A tribal leader chants a traditional prayer to open the meeting. Sung in the soft staccato rhythm of Diné, it loops over and around, pulling in even those who cannot decipher the words. The proclamation honoring the treaty, or Naalstoos Sání, recognizes that the ancestors who signed it ensured the tribe’s return to its homeland, protected the Diné way of life, and consecrated a nation-to-nation relationship with the United States. “Many were raped, tortured, and killed, including women in childbirth and children,” it reads. “Still, we persevered. Our ceremonies preserved the Diné as a people and a culture.”

“I think about all our ancestors as they signed the treaty,” says JoAnn Jayne, chief justice of the Navajo Supreme Court. “They had the wisdom, the love, the courage to think about us. They are with us today and they are watching us.”

President Begaye predicts lines of people, not just Navajos, eager to see the treaty—even though the museum has displayed a replica for years. It represents a moment, he says, when their most honored ancestors proclaimed their survival. “For them to think, as they put their X there, ‘We’re going back to the sacred mountains, to the rivers, to the deserts, to the horses, to the children and those who remain at Bears Ears and Canyon de Chelly. To return here and live. To touch the river, to touch the soil, to breathe the air.’”

The rest of the meeting concentrates on ways to celebrate the tribe and reverse its problems. They discuss a range of athletic contests—basketball, volleyball, horseshoes, archery, and rodeos. Can they bring in nutritionists? one asks. How about crafting a commemorative coin, hashtags for social media, a logo, new road signs? In the museum lobby, Vice President Nez describes his own idea and its very personal tie. One of the tribe’s younger leaders, at 42, he rose in government service as his health plummeted. “I was on the road a lot,” he says. “In Navajo culture, they feed their leaders. If I had eight meetings in a day, that was eight meals. One day, a young man says to me, ‘Mr. Nez, you tell us to take care of our bodies, but look at you.’”

At five foot eleven, he weighed 300 pounds. That was 2011. He and his wife threw out processed food, and he started to walk. Then he ran. Today he completes marathons and trains for 100-mile runs. He’s lean and healthy and speaks a gospel of starting over. Around the last week of May, he’ll lead a group of runners—anyone who wants to come along—from Bosque Redondo to Window Rock. He figures the 300-mile Long Run will take a week.

“This is not just for Navajos,” he says of the anniversary events. “It’s for all the folks in New Mexico, everywhere. It’s time for us to forgive each other and heal, to put our baggage down and move forward with a whole new outlook on life.”

Far from there, in Moriarty, which is closer to Fort Sumner than to the Navajo Nation, Ezekiel Argeanas plans his own commemoration. The Navajo teen, who was adopted at age 11, began visiting the historic site out of curiosity about his roots. “The first time I was there, it was hard,” he says. “A lot of Navajos are forbidden to go there. I asked a medicine man to perform a ceremony before I went.”

A small flock of churro sheep—the traditional, revered breed of Navajo people—grazes at Fort Sumner, and that gave Argeanas an idea for a project to earn his Eagle Scout badge. He raised money to pay a Shiprock weaver to turn the sheep’s wool into a traditional blanket dress for the historic site. He also commissioned signs to explain the sheep’s role in sustaining his people.

“This is to honor my ancestors’ legacy and their strength and knowledge and pay respect to Native weavers,” he says. “Some textbooks don’t tell about this. I’m proud to help people understand what was there.”

Finding a balance for talking about a past that some tribal members would rather keep quiet has challenged Navajo Nation Museum director Manuelito Wheeler. For him, the treaty helps provide an answer. The document is alive. To practice on the Navajo Nation, lawyers must prove their competency with its mandates. “Navajo people have respect for it,” he says. “It’s come to symbolize tribal sovereignty, the wisdom of Navajo ancestors, and their strength.” Even more, he says, its anniversary “is forcing all these discussions to happen now.”

Some tribal members hold firm to the taboo against visiting the site, he says, because “the land remembers.” Even so, the site’s managers say more Navajos have come to see it, helping to boost attendance from 3,500 to 10,000 in the past year. “That’s us saying we’re ready to deal with it,” Wheeler says. “We’re ready to acknowledge it and let it make us stronger. I hope that all people will understand this atrocity and never let it happen again. I hope America learns about this.”

FOR DECADES, FORT SUMNER was mainly known as the place where Billy the Kid died, in 1881. His grave lies on the northeastern edge of the historic site’s property. Fans of the outlaw would drive out, see the grave, visit its since-closed mini-museum, then spy the larger historic site in the distance. “It’s amazing how many visitors come to see where Billy the Kid was shot and leave changed by Bosque Redondo,” says Patrick Moore, director of the state’s historic sites. “I’ve seen it happen. They walk away crying, because it’s so emotional.”

It wasn’t always that way. Fort Sumner Historic Site used to focus solely on military life. In 1990, Navajo students found themselves perplexed at how to interpret the Bosque Redondo experience when the site gave them no clues. They wrote a protest and left it in the piled stones of a memorial cairn:

We find Fort Sumner Historic Site discriminating and not telling the true story behind what really happened to our ancestors in 1864–1868. It seems to us there is more information on Billy the Kid, which has no significance to the years 1864–1868. We therefore declare that the museum show and tell the true history of the Navajos and the United States military. We are a concerned young generation of Navajos for the future.

Twenty young men and women signed their names. Site staff found it, and the plea turned into a legislative push. It took time, but in 2005 the Bosque Redondo Memorial debuted a futuristic building that blends elements of an Apache tepee and a Navajo hogan. In 2017, officials from the historic site began meeting with both tribes in order to reconfigure its exhibits so that the voices of Mescalero and Navajo people dominate. Tours will delve deeper into that history, and students will get hands-on experience in building shelters and other survival techniques.

The new exhibits will take form in 2019, but visitors this summer can see conceptual drawings and hear the first cache of oral histories gathered for it. One thing that won’t change is a set of murals curling through a hallway between exhibit areas. One side features the work of self-described “cowboy painter” Mike Scovel, who illustrated the military side of the ordeal. The realistic style he chose grows more chilling by a trick of the convex side his mural is on. No matter where you stand, the soldiers’ eyes follow you, as do the tips of their guns. It manifests a sense of the constant paranoia tribal people must have felt. Even so, Scovel hints at human complexities: A soldier bends to pick up a dropped doll; another offers a canteen of lifesaving water as a superior lunges toward him, the word “no” on his lips.

On the concave side, Navajo artist Shonto Begay crafted a neo-impressionist interpretation of his people’s story. In Van Gogh–like strokes, he conjures men, women, and children, each one’s face individually conceived, as they trudge forward. “It’s like a dream,” he says, facing his work. “It was hard. It was painful. In the end, it was cathartic, too. I needed to express these things. Each stroke is a syllable—syllables to words, words to sentences. It’s a prayer, a ceremonial event.”

He switches to Diné, a language he was beaten for speaking after being scooped up from shepherding duties at age five and trucked to a boarding school. He ran away repeatedly, and for good, as a teen. Jail awaited parents who kept their children home. The forced assimilation scarred tribes all across the nation. Besides losing language and religion, many were baffled by their post-schooling reservation lives. Begay says he sees signs of a renaissance, with Diné lessons in Navajo classrooms and a return to traditional ceremonies. “The very fact that we can still speak the language and introduce ourselves by our clans is a victory,” he says. “We still celebrate who we are. I feel optimistic.”

Beyond the memorial building, a trail connects what’s left of the military buildings and a parade ground, the sheep pasture, a river path, and two monuments to the tribes. One is participatory: the pile of stones, with mementos left by visitors. Kachinas. Feathers. Money. A Purple Heart. A casino chip. A sobriety medallion topped by a pinch of white cornmeal. The other was built in 1994. It bears a plaque with words by former Navajo Nation President Peterson Zah. In Diné, it tells of the people, their language, the four sacred peaks, and the strength of the clans. It ends, as all Beauty Way prayers do, with four repetitions of Hózhó Náhasdlíí’ (“Beauty is restored”).

Begay stands before it and silently removes his turquoise earring, placing it on top. The soil around him is saturated with people’s suffering, but by their prayers and offerings, he and the others who come deliver a balm to the past and an oath to the future. We survived this, they say. We are here. We remember.

Hózhó Náhasdlíí’.

Hózhó Náhasdlíí’.

Hózhó Náhasdlíí’.

Hózhó Náhasdlíí’.

NAMESAKES

Bosque Redondo, Spanish for “round forest,” was likely named for a pool of water near the Pecos River. Before Spanish settlement, various tribes used the relatively sparse region for encampments; it may have served a Council Grove–type purpose.

General James H. Carleton named Fort Sumner for Civil War colonel Edwin Vose Sumner, who had established other forts in New Mexico. Before his 1863 death, Sumner advised against the fort that came to bear his name.

THE COMMEMORATION

Year-round, the historic site is open for free Wednesday–Sunday, 8:30 a.m.–4:30 p.m. It includes a small museum, shop, picnic area, the Old Fort Site Trail, and a 3/4-mile river walk.