“HILLERMAN!”

That’s how New Mexico’s favorite mystery writer answered the phone—with a newspaperman’s gruff bark. It was all bluff and habit. He loved people. Everyday folks, cops, aspiring writers, fellow authors, autograph-seeking fans, sheepherders, striking union workers ... even politicians and students.

Millions more knew Tony Hillerman through his award-winning Joe Leaphorn and Jim Chee mystery novels. I got to know him when I studied journalism at the University of New Mexico in the late 1970s. He was admired but not yet famous. As a teacher and a mentor, Hillerman helped me in countless ways, as he did so many other writers.

He never seemed to mind getting a call at home or, in later years, stopping to chat at Flying Star Cafe on Rio Grande Boulevard in Albuquerque, a mile from his house. The topic was usually writing. Did I need a blurb for my novel? Sure, he’d write one. Should I contact his editor at HarperCollins? Here’s her phone number. Or he’d deliver a perplexed, peevishly resigned lament about losing the latest Leaphorn or Chee manuscript in the digital bowels of his computer. A friend would always eventually scrape it out of some autorecovery file pit.

Those Navajo detective stories occupied huge tracts of mental territory in the overachieving Hillerman brain. Other things occupied him, too, mind and body: newspaper reporting, New Mexico politics, family, the Navajo Nation, the university classroom, anthropology, church, campus politics, movies, fishing, and the weekly poker game. That game spanned decades and gripped Hillerman so tightly that he once put off Robert Redford when the Hollywood legend wanted to meet about a film option on poker night. Priorities. It wasn’t about the cards, it was about the friends. Everything he did, poker included, fed his creative imagination; the smallest tidbit might spawn a paragraph, a page, or an entire plot in one of his novels.

To know the man, one friend says, you have to understand his hardscrabble upbringing. Born Anthony Grove Hillerman in 1925 in Sacred Heart, Oklahoma, he grew up poor and happy, attended an Indian girls’ school, and survived the Great Depression and World War II. After recovering from severe war wounds, Hillerman helped deliver a truckload of materials to the Navajo Nation, where he witnessed an Enemy Way ceremony for veterans returned from World War II, an event he drew upon in defining his future literary niche.

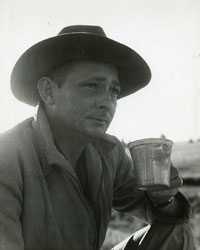

Handling copy at the UPI Santa Fe bureau, circa 1952.

Handling copy at the UPI Santa Fe bureau, circa 1952.

After attending the University of Oklahoma, Hillerman punched typewriter keys at small-town newspapers in Texas and Oklahoma. In 1952, the hand of destiny nudging his back, he and his wife, Marie, emigrated to Santa Fe. Their family grew to six children—Anne, the eldest, and her five adopted siblings, Jan, Tony Jr., Monica, Steve, and Dan. Hillerman soon became executive editor of the Santa Fe New Mexican, the capital daily.

In 1962, UNM president Tom Popejoy, another towering New Mexican, inflamed the American Legion by standing with faculty members critical of a certain loyalty oath. Popejoy delivered a ringing defense of free speech. Two days later, Hillerman published an editorial in the New Mexican siding with Popejoy and quoting Voltaire: “Liberty of thought is the life of the soul.” Impressed, Popejoy hired him as special assistant in 1963 and the family moved to Albuquerque. Hillerman helped Popejoy navigate tough legislative issues, reorganized the university news bureau, got his master’s in English, and chaired the journalism department. And now that he wasn’t cranking out news stories and editing the paper 60 hours a week, the yen to become a novelist hardened into an obsession.

By 1970 Hillerman had published The Blessing Way, the first of his genre-launching Navajo detective novels. Warm reviews rolled in. Book followed book and award followed award: the Mystery Writers of America’s Edgar Award, the Western Writers of America’s Spur and Owen Wister awards, France’s Grand Prix de Littérature Policière, the Agatha Award, the Special Friend of the Dinétah (from the Navajo, for his authentic writing about them), and so on. Best sellers attracted film deals. Imitators popped up like goat-head weeds in June.

By 2008, when he died at 83 of pulmonary failure—he would have been 90 this year—Hillerman had written more than 30 books and was undoubtedly New Mexico’s most widely read author. A friend of his remembers Hillerman mentioning millions of books sold. Most by far were the Leaphorn or Chee mysteries—he wrote 18. The specter of the Great American Novel stalked Hillerman, but the detective stories earned his spot on the top shelf of New Mexico’s literary canon, alongside Frank Waters, Mary Austin, Max Evans, N. Scott Momaday, Rudolfo Anaya, Edward Abbey, John Nichols, Cormac McCarthy, and a handful of others. His impact was enormous: If you want to get the crosscultural complexities of late-20th-century Navajo life in New Mexico, Hillerman is indispensible.

What follows is a profile of Hillerman composed of recollections from his daughter, friends, peers, students, and others. From their reflections, a 3-D image materializes, hovering around their words, alive in their memories.

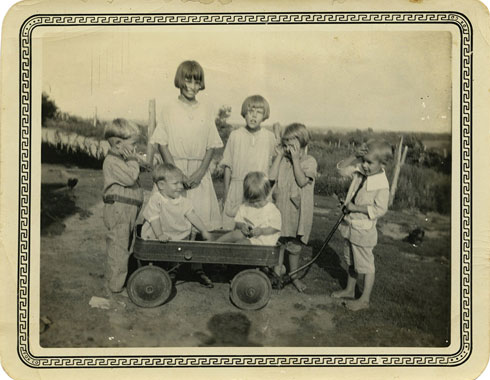

Tony seated at left in wagon, with siblings and cousins at the old Hillerman place in Sacred Heart, Oklahoma, ca. 1928.

Tony seated at left in wagon, with siblings and cousins at the old Hillerman place in Sacred Heart, Oklahoma, ca. 1928.

COUNTRY BOY

Hillerman attended St. Mary’s Academy, a school for girls from the nearby Potawatomi reservation. At one point, he organized—and gobbled up—the books in the local church’s library. He later checked out books by mail from the State Library of Oklahoma, from Pollyanna and Her Puppy to The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

Fishing in the summer of 1959.

Fishing in the summer of 1959.

Jim Belshaw, longtime columnist for the Albuquerque Journal and close poker buddy: Tony told me once that his view of the world was formed growing up in Oklahoma. In his mind there were two kinds of people in the world, broadly speaking—city and country people. And he was country. They didn’t have power. City people had power.

No one I know talks like he writes. I’ve always wondered if people who met Hillerman for the first time were puzzled about this. In conversation, he might say something about “Eyetalians” and “heeliocopters.” He might tell you he went on the Internet and looked up something on “Goggle.” His spoken voice was very different from the one that came through his fingertips and onto a keyboard.

SOLDIER

In 1943, Hillerman enlisted in the Army and was sent to fight Germans in France. He earned a Bronze Star, a Silver Star, and then a Purple Heart when he stepped on a landmine, which blew away his heel, hashed his leg, and peppered his eyes. With the help of experimental penicillin—a treatment unknown to him at the time—he recovered.

Hillerman in top row, center (grenade in lapel), with members of the 4th Platoon, C Company, 410th Infantry, France, circa 1944.

Hillerman in top row, center (grenade in lapel), with members of the 4th Platoon, C Company, 410th Infantry, France, circa 1944.

Max Evans, cowboy, native New Mexican, and award-winning author of The Hi Lo Country, The Rounders, and many other books: We never did talk about the war, the ones that actually fought in the infantry. But Tony and I had to laugh about it because we had it in common.

Anne Hillerman, daughter, journalist, and author who is carrying on the Chee-Leaphorn series with novels of her own: He never talked about the war. His autobiography was the only book he asked me to read before he published it, and I think it was because of the war stuff, even though he handled it lightly. He thought, “I wouldn’t be here if the Army hadn’t experimented

on these soldiers with penicillin.”

Jim Belshaw: Tony was an infantry grunt in World War II. That experience seemed to underlie much of the way he looked at the world. If you ever wanted to hear him talk about the abuse of power, all you had to do was ask him about a bad officer in an infantry unit.

HUSBAND

Hillerman married Marie Unzner in 1948. And without her, we might not have had “Tony Hillerman.” In Seldom Disappointed, he credits her with giving him confidence to dive into writing novels: “It was because Marie (Oh, woman of infinite faith) got me to believing I was as talented, competent, etc. ... as she believed I was.”

With bride Marie Unzner in Shawnee, Oklahoma, August 16, 1948.

With bride Marie Unzner in Shawnee, Oklahoma, August 16, 1948.

Dick Pfaff, Hillerman’s friend since about 1964, a poker pal, and longtime business supervisor of student publications at UNM, where Hillerman served on the student publications board: You can’t know Tony if you don’t ask about Marie. He told me, “The best and smartest thing I ever did was talking Marie into marrying me.” He felt that so deeply. If anyone should be canonized by the Catholic Church, it’s Marie. She was always doing something for other people, and always compassionate.

Jim Belshaw: Tony and Marie were the kind of people that, if you could vote for who your next-door neighbors would be, these would be the two you’d vote for.

FROM NEWSPAPERMAN TO PROFESSOR

After returning from the war and recovering from his injuries, Hillerman studied journalism at the University of Oklahoma, then worked as a newspaperman, honing his observational and writing skills.

In the Brazos high country of northern New Mexico in the sixties.

In the Brazos high country of northern New Mexico in the sixties.

Dick Pfaff: By the time he was 40, he had said, he wanted to be the editor of a capital city newspaper, and here he was in his thirties and he was already there.

Anne Hillerman: I think a lot of journalists want to be novelists, maybe because we run into so many interesting characters. They’re bigger than life, but they are life. When he was at the New Mexican, almost every evening after dinner he’d be working on the novel at his rolltop desk in the bedroom at the back of the house. He wrote on a typewriter.

Part of his leaving the newspaper was his increasing desire to get that novel finished. I remember him and my mom having a conversation about it. We were pretty happy in Santa Fe, and moving a family of that size was an effort, but Mom said, “As long as you’re working as a journalist you won’t get that finished. ... I think we should move to Albuquerque.” He had to go back to school [at UNM] to get a master’s to teach. He was also writing magazine articles to supplement his income.

Melissa Howard, former Hillerman student and journalist: We never called him Tony. I started with him in 1966. He seemed to have no ego involved in it at all. As a former newspaper writer and editor and wire service writer, he was very comfortable that he knew the business, and he didn’t use a textbook.

Jim Belshaw: The first time I ever got a paper back from him in class [in 1970], I remember on one page he had circled a paragraph and wrote “Ugh!” in the margin. My heart sank. On the next page, another note said, “Good.” That was all I needed. I remember how quickly, in the space of two pages, all the wind went out of my sails, and suddenly the wind came back.

AUTHOR

While Hillerman taught at UNM, he finished The Blessing Way (1970), featuring Navajo detective Joe Leaphorn. Next he wrote the political thriller The Fly on the Wall (1971). Then he returned to Leaphorn and—after selling the rights to Leaphorn—introduced Jim Chee, also Navajo. In later novels, the rights restored, Hillerman energized the stories by having the two cops work together, their distinct personalities and investigative methods creating an intriguing counterpoint.

N. Scott Momaday, Kiowa author who set his Pulitzer Prize–winning novel House Made of Dawn at Jemez Pueblo and who now teaches at UNM and St. John’s College in Santa Fe: He had possession of the spirit of story. He knew how to tell a story and he appreciated storytelling, as I do. We shared a confidence that story is universal and important. It’s at the heart of language, and he knew that.

Sheila Tryk, former New Mexico Magazine editor: He always came up with something fascinating. He’d approach you with a story and you’d say yes. You knew who would need massive editing, and he wasn’t one of them. He was a great storyteller, too, and it was sometimes hard to separate what he wrote from what he told you.

Fred Harris, author, former US senator from Oklahoma, presidential candidate, and UNM professor who attended the University of Oklahoma a few years after Hillerman, studying with many of the same professors: Tony’s prose was so spare. [One professor] taught him that adverbs are the enemy of verbs and adjectives are the enemies of nouns. I asked, “What do you mean?” And Tony says, “Instead of saying he walked slowly, say he ambled.”

Anne Hillerman: His idea was that he’d start with a mystery and go on to write more profound novels, but he discovered he really liked Joe Leaphorn and writing mysteries.

Craig Johnson, author of the Walt Longmire mystery series—now an A&E cable drama— who considered Hillerman a mentor: It’s the descriptive passages that blow me away. His dialogue is wonderful, his characters are great, but what makes me pull up on the reins and go whoa! is one of those magnificent descriptive passages that he does. He doesn’t take pages, he does it in just one paragraph—he encapsulates the vista, the geology, the color and the beauty and the magnificence of the Southwest. You learn from Hillerman that you become universal by giving the detail. It’s important to know exactly where that story takes place, who it is, and the time.

N. Scott Momaday: The land was important to him, and he did well by it. He had such a keen understanding of the Southwestern landscape and the Navajo reservation. He evoked the spirit of place extremely well. I rather think it was fortunate and to Tony’s advantage to have such a regional subject and specific cultural subject.

Dick Pfaff, recalling a boating trip on the San Juan River with Hillerman, who was the celebrity attraction: Four professional people were in one of the dories. One of them knew he was the smartest guy on the river, and he was determined to write. He wanted to know how Tony outlined his books. Tony said, “I don’t do that.” Then how do you know when to end? “I just get to the end.”

Fred Harris: I studied his writing, and I could never outline his books—I never figured out how they worked. ... When I got a two-book deal with HarperCollins, the contract said that for the second book, they would pay half the advance upon approval of an outline. I said to Tony, “I can’t outline a book in advance.” He said, “Neither can I. Don’t worry about it, just write up anything for the outline, and then turn in the book you want to do.”

CELEBRITY

Hillerman gave up teaching and left UNM to concentrate on writing novels in 1985.

Anne Hillerman: It wasn’t till Rupert Murdoch took over Harper & Row that Dad’s fiction really took off. Rupert picked writers with a strong following to do a breakout book combined with a book tour and more national promotion. It would make a difference. That was Skinwalkers [1986], which was Dad’s first on the New York Times best-seller list. Then every one was on the best-seller list.

Luther Wilson, former acquisitions editor at Harper & Row, director of UNM Press (and several other presses), and regular poker buddy: Very few writers make their living off writing. ... That pyramid is very narrow at the top.

Jim Belshaw, who traveled with Hillerman to the 1996 Super Bowl: Somebody noticed Hillerman was on the plane. The next thing we knew, a line of people almost the entire length of the plane waited patiently to get his autograph. From time to time, and with a big grin on his face, he’d look over at me and say, “You watching this?”

Tuesday [poker games] turned into a four-hour exercise in ego control: Here we had this man who was one of the best-selling authors in the world. If you didn’t know who he was, you’d never know that.

Craig Johnson: One great thing was his philosophy that you can’t help the people further up the career ladder, but you can help the people coming along behind you. He had an old-school graciousness that’s kind of a unique perspective for an author at that level of prestige. He’s the godfather of western mystery writing. A lot of big authors forget their humble beginnings.

Anne Hillerman: Dad didn’t allow much mythology to be built around him. He was the same guy in 2008, when he died, as he was in the 1940s, when he started in journalism.

NATIVE SPEAKER

In Seldom Disappointed, Hillerman writes about the literary agent who told him The Blessing Way was a “bad book” that he could improve by “getting rid of all the Indian stuff.”

Luther Wilson: [After World War II, Hillerman and his companions] stopped somewhere on the New Mexico side of the reservation. As far as he could tell, every person in the Navajo Nation had shown up to honor a few wounded Marines and go through a ceremony to get the evil out of them and reintegrate them back into Navajo society. He thought, “Why didn’t anybody do anything like that for me?” That’s what got him interested in the Navajos and interested in New Mexico. It turned out it was a great thing for the rest of the world.

Max Evans: He invented that style of writing about the reservation. A number followed him, but none were as successful as Tony.

Anne Hillerman: Originally the main character was going to be a white anthropologist, and Leaphorn would be his sidekick, but then as it developed, Dad realized Leaphorn was a much more interesting character, and luckily the editor at Harper did, too.

N. Scott Momaday: One of his strong points was his knowledge of the Southwest and of Navajo culture. I’m not sure how he came by that, but his Navajo characters are vivid and alive. The Indian has a keen understanding of that spirit of the land—it’s intrinsic to Indian life, and Tony knew that and he expressed that essence very well in his treatment of Native American culture and character.

Anne Hillerman: At UNM he had access to Zimmerman Library, which has wonderful collections of Navajo information. Dad always was very interested in religion, or in spiritual beliefs, how people imagine themselves as part of the bigger picture. And that was one of the things that really intrigued him about the Navajo—their cosmology and how complicated it was and how accepting it was of differences. That was part of his affection for the Navajo people and their culture. At UNM, he had Navajo students and he would build up relationships and go home and meet their folks. And, being a journalist, he wasn’t shy about calling up people and asking questions, and he had that good ol’ boy attitude. It wasn’t like talking to a college professor.

Fred Harris: You wouldn’t think the Navajos would accept a guy from the outside—they’d resent a white guy explaining Navajos to the world. He just empathized with them. He liked their humor. They were funny to be around. He could put himself in their shoes. He grew up with Indians and went to that Indian school.

James Peshlakai, Navajo medicine man and storyteller, who was translating Navajo to English when he met Hillerman and became a friend: We’d meet here and there and go out into the country [on the Navajo reservation] and just talk about little things. I told Tony about the plants. When we’d go walking someplace, he would ask questions: “What’s this? Do they grow in Crownpoint, too?” He had a very scientific mind. We would talk about how we teach each other to live together on this earth. He was very respectful that we [Navajos] don’t talk about death or religion. He’s the one that told us that the Navajo belief is not a religion at all—it’s metaphysical. He says, “Your belief is more like science than a religion. A religion is where people have hope, they wish for things, an afterlife.” Navajos, we don’t have heaven and don’t have hell.

Everybody wanted us to become white people and be assimilated into the American way of life. And then Tony Hillerman came along and started writing books about Navajos, and then our schools started using his books in literature classes, and the little kids started asking questions. He brought the young people’s interest back into their culture. Tony Hillerman woke us up to this.

Craig Johnson: Tony doesn’t get credit—being an Indian in 1968, when he was first writing, was not cool, not like it is nowadays. It was a bold decision to make, to have those characters be Native. But that’s kind of your job as an author: When everyone’s running in one direction, run in another direction. Here everyone was writing about cowboys, and this writer from New Mexico decided to write about Indians.

I hear Native people say they love this series with two Tontos—and the Lone Ranger never shows up!

Jim Belshaw: Who has and doesn’t have power—that’s always struck me as one of the reasons he was attracted to the Navajo people. He saw himself in them. He saw a culture that at least in one regard was very much like the one he’d grown up with—country boys and city boys. He was a country boy and so were the Navajo people, and they didn’t have power.

POKER GUY

Hillerman joined a poker group at UNM in 1965. About a decade later, Jim Belshaw and UNM public relations director Jess Price started another game for lower stakes among professors and staffers, including their buddy Hillerman. Although the membership has shifted throughout the decades, a core cadre still plays. Anne Hillerman says “the poker guys” were his best friends outside of family.

Jim Belshaw: I never met a poker player so optimistic about two pair. If someone at the table had a megaphone and was announcing a full house, Tony would call with two pair in his hand. One night a player said, “Hillerman, I finally got around to reading The Fly on the Wall. I’ve got a question about that poker scene. The hero is a reporter, which I guess is supposed to be you. I want to know who wrote that poker scene for you. You have this hero folding and folding and folding. You never folded a hand in your life. You couldn’t have written that scene. So who did?”

John Perovich, former UNM president who helped interview Hillerman for a job at the university in 1963: Tony won his share. When he was young, he was a good poker player. I remember one time we went up to Red River and the legislators were having a poker game. I wasn’t invited to play, but Tony was. He did very well.

Jim Belshaw: Tony hated missing those games. He said they reminded him of what it felt like to be in his old Army squad. We still talk about him at the poker games. His presence is always very much there. When the chatter would get to be too much at the poker table, Tony would say, “Did you birds come to talk or to play poker?” He was the only one who could get away with saying it. The players would grumble and laugh, but they’d shut up. And then half the time, Hillerman would begin telling a story of his own. It was great fun. I miss him. I sense him every time we sit down and begin shuffling the deck.

“A PRETTY GOOD FELLER”

He was a devout Catholic, but his interest in metaphysics ranged widely.

Anne Hillerman: Dad was a regular Mass-goer, but he wasn’t didactic about it. He disagreed with a lot of the official positions. He said you can’t let the Church get in the way of God.

Jim Belshaw: People of that generation and upbringing didn’t talk about it. You do your good works and the Lord sees them. If you had something troublesome going on in your life and Tony and Marie found out about it, they had a way of letting you know you were in their prayer circle.

Dick Pfaff: His spirituality and his fairness and his forgiveness and his generosity were big parts of who he was. He believed in miracles, curiously. And Marie had compassion for every living thing in the world, and that splashed over to Tony, and he was therefore incredibly forgiving.

Max Evans: Tony Hillerman wasn’t just a fine writer. He was a true gentleman who had a genuine interest in other people’s lives. He was just as sincere as you could be, what we used to call when I was cowboying “a pretty good feller.” That was the greatest compliment ever.

HILLERMAN 101: A READING LIST

The Blessing Way (1970), the inaugural Joe Leaphorn mystery, taps Hillerman’s initial fascination with the healing power of Navajo metaphysics and psychology.

The Great Taos Bank Robbery (1973) assembles a collection of Hillerman’s essays, including the title piece, first published in New Mexico Magazine. Read it for insight into mid-20th-century New Mexico.

Dance Hall of the Dead (1973) sends Joe Leaphorn outside the Navajo world to solve a mystery at Zuni Pueblo. In doing so, it punctures myths about a monolithic American Indian culture.

Hillerman Country (1991), a coffee-table book, provides Hillerman’s verbal tour of the places he wrote about, with photos by his brother, Barney. To reckon the man, reconnoiter the land he loved.

People of Darkness (1980) introduces Navajo Tribal Police sergeant Jim Chee, who’s magnetic south to the north set by his fictional predecessor and eventual collaborator, Joe Leaphorn. When Hillerman unites them in later books, their chemistry and conflict energize his cultural explorations.

Finding Moon (1995) breaks out of the mystery series all the way to Vietnam. Hillerman said it was “the closest I’ve come to writing a book that satisfied me.”

Seldom Disappointed (2001) treats the reader to several hours in Hillerman’s affable and astute company. It would be worth reading even if you’ve never read one of his mysteries. The World War II section alone earns the cover price.

The Wailing Wind (2002) explores complex relationships among Navajo heroes and Navajo villains. It’s eerie.