Above: Flags line a walkway leading to the memorial’s Peace and Brotherhood Chapel. Photograph by Richard Wong/Alamy.

VISITORS TO THE Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Angel Fire are greeted by Dear Mom & Dad, a life-size bronze by Taos artist Doug Scott. It depicts a kneeling soldier with a rifle slung across his shoulder, notepaper and pen in his hands as he stares into space, struggling with how to write a letter home. Scott’s accompanying poem reads:

The words

Dear Mom and Dad

Are written

Now what?

He can’t tell them what he is seeing.

He can’t tell them what he is doing.

His eyes

See a foreign land

His heart

Sees the other side of the world

Scott did not serve in the military himself, but he created the statue out of “a strong feeling of appreciation and love for our veterans. I did not want to commemorate the heroics of war, the battle and destruction. I wanted to touch the heart.”

Informed by stories from close friends who served in Vietnam, Scott crafted the sculpture with a particular emphasis on the face of the young man. “One side shows the gladness of thinking of home,” says Scott, “the other side is the grief of being there in the war.” Many veterans have contacted Scott to express their appreciation. “They say, ‘That is truly how it was,’ how they felt in their heart. The most powerful communication I’ve had has been with parents of deceased soldiers. They mentioned that their son wouldn’t write very often, and they didn’t understand why until they saw the sculpture.”

Other emotionally moving art resides at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, a 30-acre compound that includes historical and art exhibits, in the museum and on the grounds, plus a memorial walkway, gardens maintained by local volunteers, a gift shop, and an amphitheater, all nestled amid the high peaks surrounding the Moreno Valley. Its centerpiece, the Peace and Brotherhood Chapel, was built in 1971 by Victor and Jeanne Westphall, the grieving parents of U.S. Marine Corps First Lieutenant David Westphall, after he was killed in Vietnam in May 1968.

Above: A sculpture by Paul Burge (art design by James Anderson). Photograph by John McCauley.

The chapel's white walls, which swoop up, converging in a dramatic peak, echo the inspiring backdrop of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. “It’s a place where people can go and sit and cry and heal and pray,” says Walter Westphall, David’s younger brother, who served as an Air Force pilot. The art in the adjacent museum building, he says, is valuable in a different way. “It’s of importance for veterans who can come and reminisce and realize that someone has tried to show what it was like for them. Art expresses things more than documentation.”

D.B. Herbst, the memorial manager and also a Marine Corps veteran, agrees. “Looking at the art takes visitors back to the war and gives them a way to talk about their experiences. It helps them shuffle through their feelings. A lot of them have survivor syndrome because their buddy was in a foxhole with them and their friend got killed and they survived, so it opens them up to talk about their experience. They can tell their families about it. A lot have never talked about it before.”

VIETNAM ELEGY, BY ALBUQUERQUE ARTIST Denham Clements, is one of the prized pieces in the memorial’s permanent collection. Having served in the Marines in Vietnam, Clements left the military in 1969. It took 42 years before he could bring himself to start the painting, even though he had long ago established himself as an artist, specializing in photorealism.

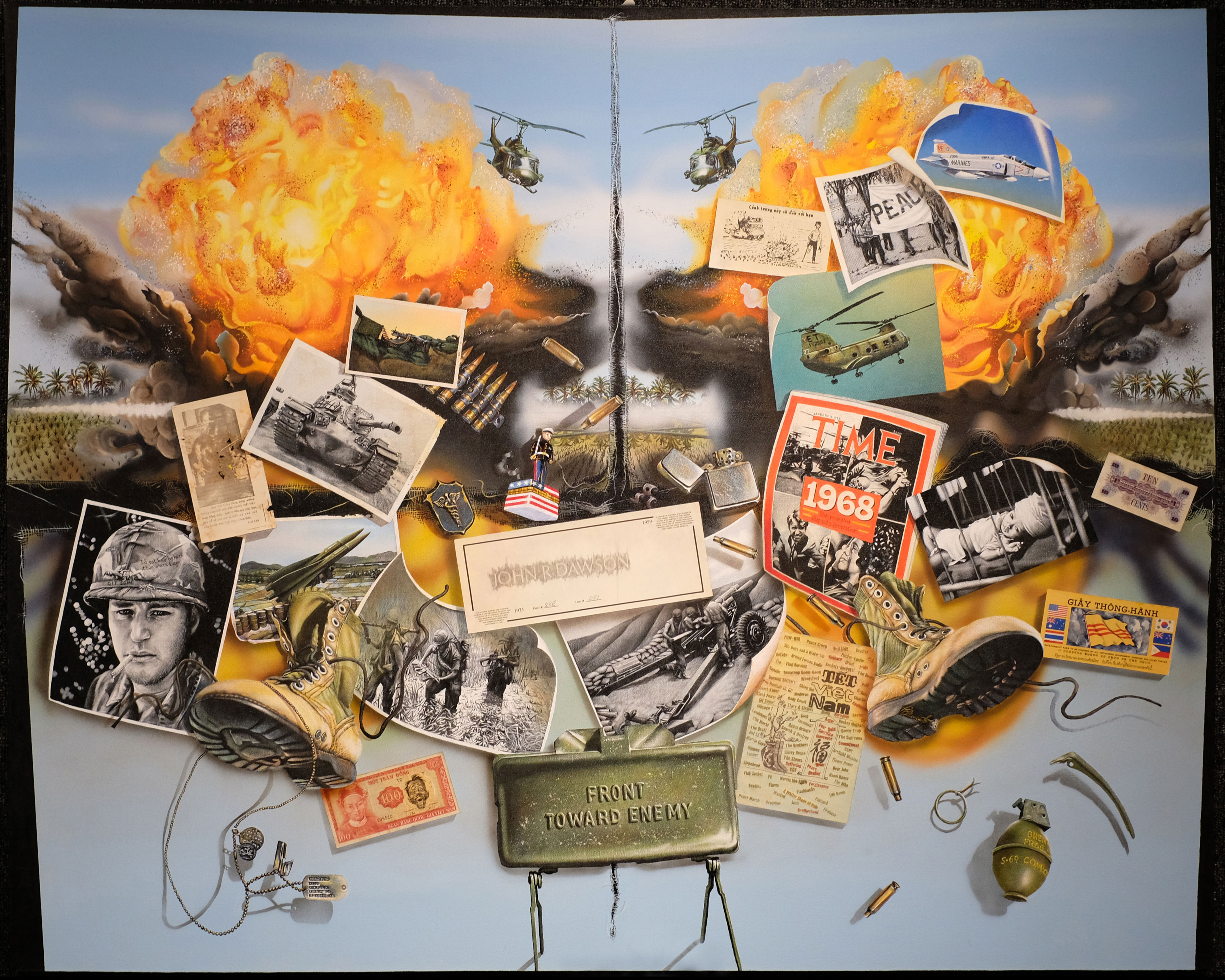

Above: Vietnam Elegy, by Denham Clements. Photograph by John McCauley.

“I wasn’t quite ready to do it emotionally or technically,” says Clements. “But as time progressed, I wondered if I could consider doing a Vietnam piece because I knew I wanted to get some things off my chest.”

Clements didn’t have a plan for the painting. “I had brought a lot of things home from Vietnam and I didn’t know why and they sat in a trunk.” So he hauled out the trunk. What he found inside fueled his imagination.

“When I put the first brushstroke on the canvas, I was committed. I knew quickly it was not a weekend event. It was going to take as long as it took.” The ultimate tally: two years and three months. During that time, Clements didn’t work on any other painting.

“Day by day, I didn’t know what I was doing next. I was having to relive a lot of things and do an enormous amount of research to make sure it was 100 percent truthful. It became cathartic.”

The oil-and-acrylic painting tells a story through hyper-detailed images of jungle boots, a Claymore anti-personnel mine, Huey helicopters, dog tags—icons of the Vietnam War that Clements felt would transport not only him but other veterans back to that time and place. He collaged propaganda leaflets and included a rubbing he made of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., when he visited it in 1988. It bears the name of John R. Dawson.

“I’d trained with him. He was a man of character and a very brave Marine,” Clements says in one of the videos he has made and posted on his website, to talk about all the elements of the painting. (Posters and prints are also available at the website.)

The positive response to the painting was validating for Clements. “My feelings, my experiences, were shared by others. The message was hopefully going to be ‘I am one of you, I understand. We did the right thing, we were brothers together in this conflict—this is a tribute to you and all the families.’

“Her conception and her presence at the Angel Fire memorial are rooted in healing,” Clements says of Vietnam Elegy. Several other larger national venues wanted the painting, but he has a significant emotional bond with the Angel Fire memorial, which he describes as “a shrine. Among veterans it’s sort of a holy place.”

When he came to New Mexico in 1975, he drove to Angel Fire. “Up on top of the hill I see these spires, and it’s the chapel. I walked inside and it was like I returned to the womb. I began to understand what the Westphall story was. I understood their loss and sacrifice.” That night, Clements slept outside the memorial in his station wagon, and the next day he got an apartment in nearby Eagle Nest before moving to Taos Ski Valley for four years. That was when his painting career started. “It’s come full circle. It’s absolutely the perfect place for Vietnam Elegy.”

Above: Where Eagles Soar, by Eric Orlemann. Photograph by John McCauley.

“TO ME, THE THINGS THAT LEAD veterans to create visual art are no different than what inspires them to write about their experiences,” says Steven Trout, author of the new book The Vietnam Veterans Memorial at Angel Fire: War, Remembrance, and an American Tragedy. “There is all kinds of research about the benefits of putting experiences in narrative form, especially when violent or traumatic.”

Trout also juxtaposes the visual impact of the chapel against wall-style memorials, such as the one in Washington, D.C., designed by Maya Lin, with its black granite and straight lines.

“What’s striking about the memorial at Angel Fire is that aesthetically it’s so profoundly different. It’s not horizontal, it’s a soaring structure, you feel kind of lifted off your feet when you look at it. Ted Lunas’s design brilliantly situated that memorial, making it one with the landscape, organic.”

“It’s interesting to see what the design means to different people,” says Chuck Howe, president of the David Westphall Veterans Foundation and himself an Army Vietnam veteran. “Some look at it as a fallen angel.” Howe is also president of the National Veterans Wellness and Healing Center, in Angel Fire, which includes tours of the memorial during seven-day retreats. Just seeing the exhibits proves therapeutic for the veterans, he says, but they also make their own art, such as creating masks to represent their feelings.

Above: A memorial to David Westphall and the fellow Marines lost in battle. Photograph by John McCauley.

Albuquerque author Jim Tritten participated in a retreat and was especially moved by the museum’s smaller-scale replica of the Vietnam Women’s Memorial in Washington, D.C., by Santa Fe artist Glenna Goodacre, and by Paul Burge’s sculpture of a man’s hands bound in barbed wire in the prisoner-of-war section.

“The hands to me represented shackles binding a prisoner who was pleading for help,” says Tritten. “I could see them thrust through wire fence or bars asking for help. The women’s statue was a reminder that women served. Died. And were not in the forefront of our consciousness at the time. It’s a perfect example of art as a way to make a point better than with words. With all of the male-oriented exhibits—aha! Women were there, too.”

Sometimes, Howe says, people visit the memorial and can’t bring themselves to go inside. “For one visitor it took 13 times. He’d get out of the car, walk a little ways, and then change his mind and go back.” The place represents a trip into a past that can still be far too present for many men and women and their families, which is why the Westphalls imbued it with a sense of peace, and of healing.

Above: Dear Mom & Dad, by Doug Scott. Photograph by ML Pearson/Alamy.

“Victor Westphall was extremely idealistic, and he was hoping that this site would really become the hub of a global peace movement,” says Trout.

The fact that the chapel itself is a work of art and in harmony with the soaring peaks, green grass, wildlife, and an enormous sky mattered to Victor and Jeanne Westphall. “The setting of the memorial in the mountains and with the sunrise and the sunset, the elk—to me, all of that is art,” Howe says.

POINT OF HONOR

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial is just off US 64, at 34 Country Club Road, in Angel Fire. Its museum is open daily, except Christmas and Thanksgiving. Hours vary by season. The chapel is open 24 hours a day, every day of the year.

In addition to the permanent collection of art and documentary exhibits, the museum is showing a special exhibit on the history of the chapel, including artwork of it, in the lead-up to its 50th anniversary, in 2021. A new exhibit on the Medal of Honor highlights New Mexico recipients.

Each year, veterans and their families gather at the park for Memorial Day ceremonies. During this year’s event, Steven Trout launches his new book, The Vietnam Veterans Memorial at Angel Fire: War, Remembrance, and an American Tragedy. For more details on all the day’s events and the site. (Learn about Memorial Day events statewide at nmdvs.org/events.)

A new documentary, On This Hallowed Ground: Vietnam Memorial Born from Tragedy, for sale in the gift shop and available on Vimeo, tells the powerful story of David Westphall and his parents’ building of the Peace and Brotherhood Chapel.