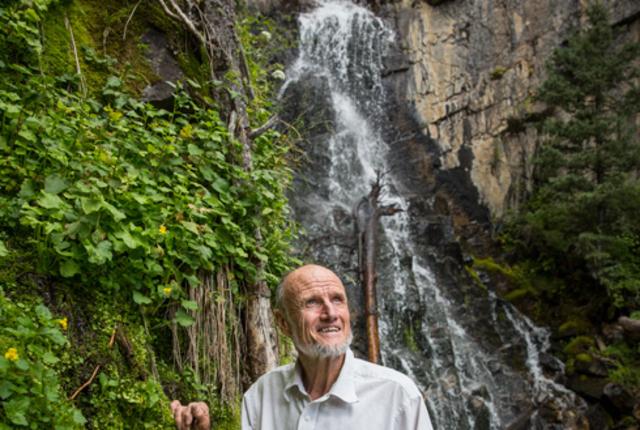

(above) Scott at North Fork Casa Falls, in the Carson National Forest.

There are no signs to North Fork Casa Falls, in the Carson National Forest near Mora, on the eastern flanks of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. The county road that will take you there (B-028, off NM 518) is tricky to find. But pay attention from the highway and you’ll discover the unmarked turn, and finally the rocky dirt road that leads to a 50-foot cataract that spills dramatically over a granite cliff deep in a lush canyon—a perhaps unexpected attraction in high-desert New Mexico. This spectacular formation, and many more like it, might still be secret if it weren’t for the decades-long obsession of Doug Scott, a White Rock–based artist who has dedicated much of his adult life to finding and documenting every waterfall in the state.

Although he’s been exploring obsessively for decades, Scott is hard-pressed to explain the source of his passion for waterfalls. “Ever since I was a small child, the fascination was just there,” he says, “and it has only gotten stronger. It seems involuntary and uncontrollable.”

When Scott, 64, sets out to find a new waterfall, he moves at a fearless clip. He pilots his old Jeep Cherokee like a rally driver, barely slowing for exposed roots and rocks or bends in the road. On foot, he’ll often cover 20 miles or more a day in search of a cascade. He travels light and fast, packing little more than water, beef jerky, a camera, and some duct tape for emergencies. Though he’s hard-charging on the trail, with the face of an outdoorsman, one is struck by Scott’s easygoing disposition and soft-spoken voice. Well-worn jeans and a fleece jacket are his standard wardrobe.

Not just any downhill flow of water will make Scott’s list, which he keeps on his website (dougscottart.com) and ultimately files with the World Waterfall Database. He records only perennial flows that run over bedrock; monsoon-fed flash floods don’t count. The cataloging started back in the 1980s, and Scott takes a break only during the winter. Nothing else stops him, though some things have tried. Over the years, he’s taken a few minor tumbles and, on several occasions, barely avoided stepping on a rattlesnake.

His most intense close call, he says, occurred along the South Fork of the Hondo, in the Wheeler Peak Wilderness not far from Taos Ski Valley, one summer. “I was in a hurry, and I came on really quick to a mother bear and her cub at close range, like 30 to 40 feet,” Scott recalls. “She instantly started charging me.” Scott raised his walking stick to make himself appear larger, and it worked. The bear pulled up short.

“I made a lot of threatening noise and motion,” Scott continues. He slowly backed away from the animal. “The instant she and I lost eye contact behind an obstruction, she gave a deep grunt and bounded away with her baby.”

Thanks in part to Scott, you don’t have to take such risks to glimpse the falls for yourself, unless you want to. He’s published four books on the state’s waterfalls, and his website has become a virtual directory of them, including pictures, descriptions, and directions.

“Only about half a dozen waterfalls even show on maps,” says Scott. “And yet I’ve found literally hundreds.”

Williams Falls feeds into

Williams Lake, near Taos Ski Valley

Born in Oregon and raised in Albuquerque, Scott has long had a close relationship with the woods. He went hunting with his father, but rather than shoot he’d put down his rifle and tell the deer in his cross-hairs to shoo. Scott didn’t bring home much venison that way, but he did get to check out some waterfalls while gaining outdoor experience.

After attending the University of New Mexico, where he studied architecture and pole-vaulted for the track team, Scott moved to Taos and opened Taos Mountain Outfitters in 1969. At the time, the town had a small but fast-growing community of adventure enthusiasts, and Scott hired his friends to sell hard-to-find climbing, mountaineering, rafting, and hiking goods. The store is still thriving on the Taos Plaza, though Scott sold his share in the business years ago.

In 1971, before he got out of the business, Scott chartered a river-guiding company—one of the early pioneers of the sport, and the first commercial operator to take clients down the Box and other now well-known whitewater stretches of the Río Grande. “I had a bunch of hippies working for me, and my guides and I named all the rapids,” Scott says. “We’d go down and run the Gila River on wet years. Nobody knew what was around the next corner. We were running it by the seat of our pants.”

Apart from his guiding and retail work, Scott made money as a part-time carpenter. But for most of his life he’d wanted to be an artist. At Albuquerque’s Manzano High School, instead of focusing on the assignment and lectures, he drew “the pretty girls in class.” But it would take years for Scott to commit to making art full-time. “I was afraid of it financially until after I turned 30,” he says. His wife, Vivian, challenged him to fulfill his dream and open a gallery, so they took a shot and opened the Doug Scott Showroom in Taos. (The art business is still going but is now exclusively online.)

The gallery mainly featured woodcarvings at first. On advice from a friend, Scott moved into carving marble. The stone demands a very different set of skills, but he became so adept with it that he would later work on what he claims was the biggest block of marble ever carved in the United States. This 72,000-pound chunk of stone had to be transported on a multi-axle heavy hauler, operating under special permission. A video of the process shows a truck-size block of white rock being craned out of a quarry before Scott transformed it into a nine-foot buffalo that now stands on the campus of West Texas A&M University, near Amarillo. Among other places, Scott’s sculptures are also featured prominently at the Taos Convention Center and the Philmont Scout Ranch, near Cimarrón.

Scott’s professional success in his thirties coincided with a reemergence of his childhood fascination with waterfalls. In his spare time, he began to study maps and plan outings. Routine jaunts in the woods became organized reconnaissance missions. “My waterfall radar works pretty good,” he says. “But I cheat a little with the USGS topo maps and Google Earth.”

Despite his track record, Scott says that there are still many undocumented falls in New Mexico. “There are so many waterfalls here, I won’t live to find them all,” he says. But every year brings a new exciting round of discoveries, and even some of the well-known falls can prove exciting.

For instance, Bandelier National Monument’s Lower Falls, normally a slow trickle, became a gusher last season. Following the 156,500-acre Las Conchas Fire in 2011 and the consequent loss of water-absorbing foliage, El Rito de los Frijoles, in the center of Bandelier, experienced several huge flash floods, one of them providing the best surprise of 2014. The Rito de los Frijoles typically runs at a rate of about one cubic foot per second (cfs). But during heavy rains the stream can swell to 9,000 cfs—more than the Río Grande. The floodwaters have rearranged the canyon below both the Upper and Lower Falls, creating a dramatic plunge pool at the base. The changes in the landscape rendered the Lower Falls temporarily inaccessible, but the Park Service is working to repair the trail. Those interested in a visit should call ahead to check on status.

This year, Scott is turning his attention to the Gila Wilderness, in southwestern New Mexico. The deep canyons there, he surmises, are likely packed with waterfalls. Will he find a new favorite? That’s pretty likely, he says. After years of exploring, Scott already knows which one it will be: “The next one I find.”

Jason Strykowski wrote about extreme kayaker Ed Lucero in the May issue. Read the story at mynm.us/edlucero.

Frijoles Falls, in Bandelier National Monument.

Frijoles Falls, in Bandelier National Monument.

NEED TO KNOW

NEW MEXICO FALLS

You don’t have to bushwhack 20 miles through remote canyon country to find spectacular New Mexico cascades. Doug Scott’s website dougscottart.com lists falls that are accessible by easy strolls, as well as ones that involve more adventurous expeditions. Before you set out, Scott offers a few tips. Most important: Always hike with a partner. He also advises packing some basic hiking supplies, including extra food, electrolyte-enhanced water, a GPS unit and map, medical tape, and a camera. Scott has some tips for aspiring photographers, too. “Direct sunshine is really hard on a waterfall picture,” he says. “You really want solid overcast to get your best image.” That rule of thumb might make July and August, with the onset of monsoon clouds, the most desirable months for waterfall hunting. Conversely, summer storms can be dangerous in the canyons. Fortunately, there are plenty of other seasonal opportunities to get on the trail. “Sometimes the waterfall season might start in March or April,” says Scott. This summer, “the north high-country snowpack is a little below average,” he adds. “But the falls should flow just fine this summer and into the fall.”

WILLIAMS FALLS AND LAKE

Summer hikers will find that the popular Williams Lake is fed by a 30-foot waterfall. From the Taos Ski Valley, drive through the parking lot to Twining Road and then on to Kachina Road. Park by the Kachina Lift and the Bavarian Lodge. From the parking lot, hop on Forest Trail 62, which parallels a small creek and a dirt road before passing through a spruce glade and into a meadow. To reach the falls, head east just before the lake for about 300 yards.

TRAIL LENGTH: 2 to 2.5 miles

TRAIL DIFFICULTY: Easy to moderate

WATERFALL HEIGHT: 30 feet

GPS COORDINATES: 36°33.238’N, 105°25.940’W

SEASON: June through October

INFORMATION: Carson National Forest;

mynm.us/williamsfalls

THREE RIVERS WATERSLIDES

This series of gentle falls running over solid bedrock is close to Three Rivers Trail (T44), in the Lincoln National Forest near Tularosa. Take US 54 north from Tularosa 18 miles to Forest Road 579. Drive past the petroglyph site to the campgrounds. Hike 3 miles up the trail to the point where the falls run parallel. Adventurous types should bring bathing suits, as it’s possible to slide down these little chutes on one’s rear end, but they can expect a few dings and scratches from the rough stone.

TRAIL LENGTH: 6 miles

TRAIL DIFFICULTY: Easy to moderate

WATERFALL HEIGHT: 100 feet over multiple tiers

GPS COORDINATES: 33°24.500’N, 105°50.821’W

SEASON: May through October

INFORMATION: Lincoln National Forest;

mynm.us/three_rivers

NORTH FORK CASA FALLS

This series of cascades on the northern fork of the Río de la Casa drops 1,500 feet down a dewy canyon. Drive north from Mora on NM 518 to the small town of Cleveland. Take County Road B-028 west to County Road B-029. Turn west onto Forest Road 113 and look for the wide-open Walker Flats. Park in a clear spot and walk west toward the denser forest. Hikers should be able to spot Trailhead 22 at the border of the Flats and take Forest Trail #269 uphill and above the falls. Alternatively, walkers can venture off-trail into the canyon.

TRAIL LENGTH: Varies

TRAIL DIFFICULTY: Moderate to difficult

WATERFALL HEIGHT: Many up to 50 feet

SEASON: Spring through fall

INFORMATION: Santa Fe National Forest;

mynm.us/riodelacasa

UPPER FRIJOLES FALLS

One of two falls in the center of Bandelier National Monument, the Upper Frijoles is the only one currently accessible, due to the flood damage. Upper Frijoles is located on the Falls Trail that starts behind the Visitor Center parking lot. From there, head south toward the Río Grande. The trail winds alongside the small El Rito de los Frijoles for about a mile and a half before it reaches a dramatic viewpoint of Upper Frijoles Falls. Unfortunately, floods have washed the trail away from that point, leaving a sheer cliff where the trail used to continue to the Lower Falls and the Río Grande.

TRAIL LENGTH: 3 miles

TRAIL DIFFICULTY: Easy to moderate

WATERFALL HEIGHT: 80 feet

GPS COORDINATES: 35°45.750’N, 106°15.575’W

SEASON: All year

INFORMATION: Bandelier National Monument;

nps.gov/band

FILLMORE FALLS

From I-25, take exit 1 (University Avenue/Dripping Springs Road) in Las Cruces and head east. The road ends at the Bureau of Land Management Visitor Center parking lot. Follow the Fillmore Canyon Trail until it runs directly into the falls. On the trail, be wary of disused mine shafts. During the rainy season, a pool forms at the bottom of this slickrock waterfall. This gem is part of the recently created Organ Mountains–Desert Peaks National Monument, managed by the BLM.

TRAIL LENGTH: 1.5 miles

TRAIL DIFFICULTY: Easy

WATERFALL HEIGHT: 40 feet

GPS COORDINATES: 32°20.360’N, 106°34.620’W

SEASON: All year, but best flow in spring

INFORMATION: Bureau of Land Management (BLM);

mynm.us/ fillmorefalls

HOLDEN PRONG CASCADES

This segmented waterfall in the Gila National Forest tumbles over multiple pitches. Take NM 152 west from Hillsboro for 17.8 miles. Park at the Emory Pass Vista and pick Trail 79 heading north. After about 8 miles, swing right on Trail 114 North at the Holden Prong Saddle. Trail 114 hits the falls in 3.2 miles. The Silver Fire impacted much of this area, but there are great views of the Black Range along the way.

TRAIL LENGTH: 22.4 miles round-trip

TRAIL DIFFICULTY: Moderate

WATERFALL HEIGHT: 40 feet

SEASON: Spring through fall

FOR MORE INFORMATION: Gila National Forest Black Range Ranger District, (575) 894-6677;

fs.usda.gov/recarea/gila/null/recar

Check ahead with the sources of information provided here for weather forecasts, seasonal closures, and fees. Always be careful when venturing off-trail. Some falls require navigation by GPS.