IF ELFEGO BACA—who once held 80 rampaging Texas cowboys at bay for 36 hours—had lived to see his life portrayed in the Walt Disney TV-series [Elfego Baca], he would have enjoyed it immensely. He might not have authenticated all the incidents as being strictly historical, but he would have relished the drama and excitement.

He was something of an actor himself and he loved to dramatize incidents of his own life in conversation with friends or interviewers. In the last two decades of his life, I visited with him and interviewed him frequently for feature stories. He often recalled “the old days,” and with gestures and grimaces and a quick draw of the .45 he kept in his desk drawer, he made spectacular productions out of incidents in his flamboyant past.

Elfego had a robust sense of humor and he loved particularly to recount the amusing incidents.

Once I dropped into his office to find him shuffling through some old papers. When he came upon a transcript of his testimony before a congressional committee in 1914 relative to conditions in Mexico, he made no further effort to find the missing paper but started talking about the old congressional hearing and about Pancho Villa, whom he had once represented as American agent before they came to the parting of the ways.

The transcript of the hearing quoted Elfego as saying that Pancho Villa had been a rancher.

“He had a horse and cattle ranch,” he told the committee.

“Where did he buy his horses and cattle?” the Chairman, a Mr. Flood, asked.

“Where did he buy them?” Elfego repeated. “He didn’t. He just sold them.”

He went on to tell the difficulties of doing business with Villa, since a visitor would have to run the gauntlet of a couple hundred guards.

One of the congressmen asked if he would have been willing to cross the border to discuss business with Villa.

“He invited me over twice,” Elfego replied. “I still have the matter under consideration.”

The reason he had the matter under consideration was that Villa had put a price of $30,000 on Elfego’s head. They had quarreled and separated, but when he left, Elfego took as a souvenir the bandit’s pet rifle—which was one of four that had been specially made for him at a cost of $500 each.

Later when Elfego became American agent for General José Ynez Salazar, a bitter enemy of Villa, the bandit decided that was just too much and he offered a $30,000 reward for delivery of Elfego to him in person.

Elfego once told me that he had figured out a scheme to collect the $30,000. He planned to have himself delivered to Villa’s men on the American side of the border for the payment of the reward. Then two expert marksmen were to deliver him from the Villa agents before they reached the Mexican side of the border. But Villa must have suspected trickery, for the plan fell through.

ON THE COVER

The wide-open spaces of New Mexico, so familiar to followers of Western TV “horse operas,” are pictured in this cover photograph, made by Harvey Caplin west of the Río Grande near Bernalillo. TV producers have used New Mexico locales for the Elfego Baca series (near Santa Fe and Cerrillos) and for Rawhide (near Tucumcari).

The first big money that Elfego earned was not the $30,000 reward but the fee he received for representing General Salazar, who was an important officer in the Huerta Revolution in Mexico in 1913. General Salazar sought refuge in the United States while being hotly pursued by a rival army. He was charged with violation of the Neutrality Act and interned at Fort Bliss and later at Fort Wingate, near Gallup. The Salazar faction was anxious to get the general out of jail, and Elfego, whose reputation was well-known in Mexico, was employed to defend him.

Elfego’s longtime friend, W. A. Keleher, attorney and historian, recalls that Elfego’s instructions were to go to Washington and present himself to a certain vice-president of the Riggs National Bank, and there to identify himself and receive his fee for the Salazar defense.

In Washington, Elfego conferred with the official and after the preliminaries, he was told: “Mr. Baca, we have been instructed to pay your fee, and if you will tell me how much—I will give you the money.”

After a bit of hesitation about how much he should ask for—he thought the amount had been settled upon—he decided to make it big, and reaching in his mind for the largest possible sum acceptable (perhaps he was thinking of that $30,000 reward Villa had put on his head), Elfego announced boldly, “My fee will be $30,000.”

“Very well,” said the official, “I will issue a deposit slip in your name and you will be free to check on it as you wish.”

As they were saying goodbye, the official complimented Elfego on the reasonableness of his fee and let it slip that they were prepared to pay up to one hundred thousand dollars!

As Elfego later related to Keleher, he gulped and could only manage a sickly smile as he fumbled his way out of the bank into the open air.

General Salazar did get out of jail, but it was in a manner for which Elfego denied any credit—or blame—or even any participation.

The general’s case had dragged on for months, and out of the violation of neutrality charge, a charge of perjury had been added, and the general’s case was set for the fall term of court in Albuquerque. In November 1914, General Salazar was moved from the Fort Wingate detention camp to the Albuquerque jail. A few nights later, on November 20th, the jailer was overpowered in his office, tied up, and his famous guest was delivered from his cell.

Elfego and a number of others were indicted for complicity in the jail break, but Elfego had a perfect alibi. At the very moment that General Salazar was being released from jail, Elfego was standing at the bar of a downtown saloon. He could be very precise about the time because he asked a very prominent Albuquerque attorney the time so he could set his watch!

Elfego was a contemporary of Billy the Kid, and he used to tell a story about having met the Kid when they were both about 16 or 17 years old. They rode into Albuquerque together and, after a couple drinks, sent the crowd in an Old Town saloon to the exits and under the tables when Billy surreptitiously began firing his pistol into the air. A deputy came over to arrest the Kid, but looking him over, saw that he was not carrying a gun in his holster. The deputy and bartender still had their suspicions, however, and the Kid and Elfego were asked to leave.

After they were out of sight, the Kid lifted his sombrero, removed his pistol from his head and replaced it in the holster.

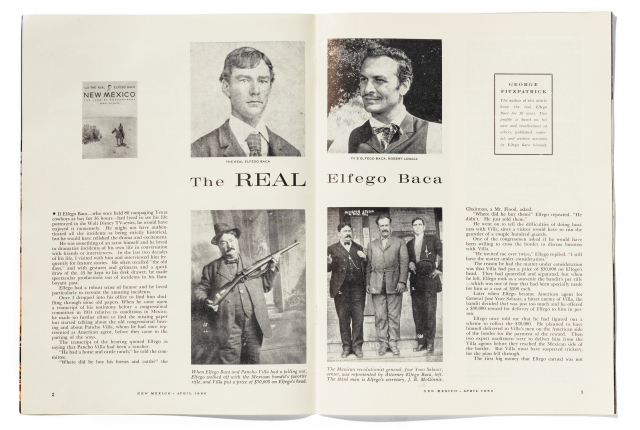

from left When Elfego Baca and Pancho Villa had a falling out, Elfego walked off with the Mexican bandit's favorite rifle, and Villa put a price of $30,000 on Elfego's head; The Mexican revolutionist general, José Ynez Salazar, center, was represented by attorney Elfego Baca, left. The third man is Elfego's secretary, J.B. McGinnis.

In his first 50 years, Elfego held so many offices and engaged in so many occupations that sometimes he couldn’t readily recall them all himself. He was clerk in a store, a deputy sheriff, a deputy U.S. marshal, county clerk, mayor of Socorro, county school superintendent, an assistant district attorney, a special agent for a cattlemen’s association. He dabbled in mining and was a bouncer in a Juárez night club, American representative for Pancho Villa and other revolutionaries, a private detective, a practicing attorney, a publisher and editor, and a restaurant operator. He had read law in the office of Judge H.B. Hamilton in Socorro in the early 1890s, and was admitted to the bar in 1894, at the age of 29.

When he became sheriff of Socorro County (1919–1920), he adopted the unusual procedure of sending letters to persons indicted, instructing them that they were under arrest and to report to the sheriff pronto; and if they didn’t, he left the distinct impression they were to be considered as resisting arrest and he would proceed accordingly. So great was his reputation among lawbreakers by this time that his letter writing was almost 100 percent effective.

Once he even sent a prisoner after an escaped prisoner—and, as instructed, they both came back!

In 1905 and 1906, Elfego served as district attorney of Socorro County, and according to a later political campaign brochure, “Mr. Baca distinguished himself with energy and ability in all business in his charge, and at the time it was difficult enough to serve as District Attorney in those counties.”

Eugene Manlove Rhodes, the great Western novelist, was not so charitable toward Elfego. In an early novelette, Hit the Line Hard, he based a character named Octaviano Baca on the district attorney at Socorro. The novelette portrays the D.A. as something less than a distinguished public servant.

But of unique interest even today is his description of Octaviano Baca: “A gay man, a friendly man, his manner was suave and easy; his dress, place considered, rigorously correct—frock coat, top hat, stick, gloves, and gun. The gun was covered, not concealed, by the coat; a chivalrous concession to the law, of which he was so much an ornament.”

In his 1959 bibliography of Rhodes’ writings, Bar Cross Liar, W.H. Hutchinson relates that in a copy of the early novel autographed for his niece, Amy Davison, Rhodes had written of the book: “The town—truly portrayed—is Socorro, New Mexico. Baca and Scanlon are daring portraits. Elfego Baca swore for years that he would kill me for same but relented as the years mellowed him.”

In later years, Elfego, in fact, was quite generous in saying nice things about Rhodes, and in 1928, after Rhodes had written something about Elfego, the latter wrote to the novelist saying: “I am sorry my English is not rich enough to aid me in expressing my sincere thanks to you for what you have written about me in the newspapers. Nevertheless, allow me to thank you, and remember that at any time that I can be of any service to you, all you have to do is to command me.”

Although Elfego received his schooling and law training in an era when the writing of briefs and letters was stilted and formal, nevertheless, his letters, like the one to Gene Rhodes, were usually warm, friendly, and casual.

For example: After he had appeared on Bob Ripley’s “Believe It or Not” radio program in a remote broadcast from Santa Fe back in 1940, he wrote to ask me to get him some copies of the local newspaper, but he did it in this charming manner:

“Estimado Amigo:

“A pretty girl passed by my office door today at 3 p.m. and she showed me a picture of Bob Ripley and I, taken on the 24th of May, 1940. She took the picture with her.

“Will you please send me a copy of this paper? Or if you can telephone the Santa Fe New Mexican and advise them to send me about half-dozen copies and I will remit the amount promptly. Tell them you will be my security until I pay the bill ...”

Here’s another sample, written just before his 77th birthday:

“My dear good friend:

“You know that on the 27th of February, 1942, it will become my birthday once more, and I would like to ascertain from you if you are going to be here in Albuquerque any time before that.

“I would like to have a talk with you and when you intend to come, write to me two days ahead so I will know you are coming, so you and I can go have a real Mexican dinner ...”

Read more: The first chile feature by New Mexico Magazine describes the evolution of the chile.

QUOTABLE

“Easter month is shrine-visiting time. New Mexico, a devoutly religious state, has many shrines, both public and private. In almost every placita you’ll find a personal shrine or two, or maybe more. Little niches filled with family saints, or small chapels for special family saints. One of New Mexico’s most historic and older shrines is that of the Virgin of Portales, in the foothills of Mt. Taylor.”

—Betty Woods, “Trip of the Month: Shrine of the Virgin of Portales”

He wrote letters to friends, acquaintances, politicians, and strangers on every conceivable subject. In my files, I have a copy of one written to an Albuquerque attorney in which he started out his letter this way: “We heard your talk on the radio last night and it was good. Congratulations—Shake.”

Elfego is well on his way to becoming a Southwestern legend—just as Billy the Kid has become a legend. In Elfego’s case, it will be on the side of law and order, stemming from his feats as a law officer and his famous fight at Frisco.

And there is plenty of material in his real-life story to provide the fabric for a voluminous legend to clothe him with a fictional character.

In her book, Albuquerque, published in 1947, Erna Fergusson relates that in the twenties Elfego decided to publish a weekly newspaper and bought a press in Denver. When payments became delinquent, a collector came down from Colorado to put pressure on Elfego for some money. Elfego must have frightened the collector half to death because he turned up in a few minutes at the law office of Attorney Keleher to tell his story.

Keleher, a longtime friend, called Elfego and remarked that these were civilized times and suggested there should be no rough stuff.

“What did I do?” Elfego asked innocently. “I just took my gun out of the drawer while I looked for the papers. When I looked up the man was gone.”

Incidentally, the name of the paper was La Tuerca (for a bolt and nut insignia he used for his personal political club). According to Elfego’s biographer, Kyle Crichton, the subscription price was $2.00 to good citizens, $5.00 a year to bootleggers, and $5.00 a month to prohibition agents.

Crichton, who later became a New York editor and author, wrote a full-length biography of Elfego in the twenties, called Law and Order, Ltd. It had only a casual sale then. Today copies are eagerly sought after, and the book is a collectors’ item.

But it was not Elfego’s first appearance in a book. He already had a prominent place in James H. Cook’s Fifty Years on the Old Frontier and Capt. William French’s Reminiscences of a Western Ranchman. Both French and Cook were ranchers in southwestern New Mexico at the time of Elfego’s Frisco fight, and Cook was responsible for arranging a truce.

In the Frisco fight, Elfego was one Ione man against 80 Texas cowboys. When the fight was over, more than 4,000 shots had been fired, and even a broom handle was riddled with bullets.

GEORGE FITZPATRICK

The author of this article knew the real Elfego Baca for 20 years. This profile is based on his own and recollections of others, published material, and written accounts of Elfego Baca himself.

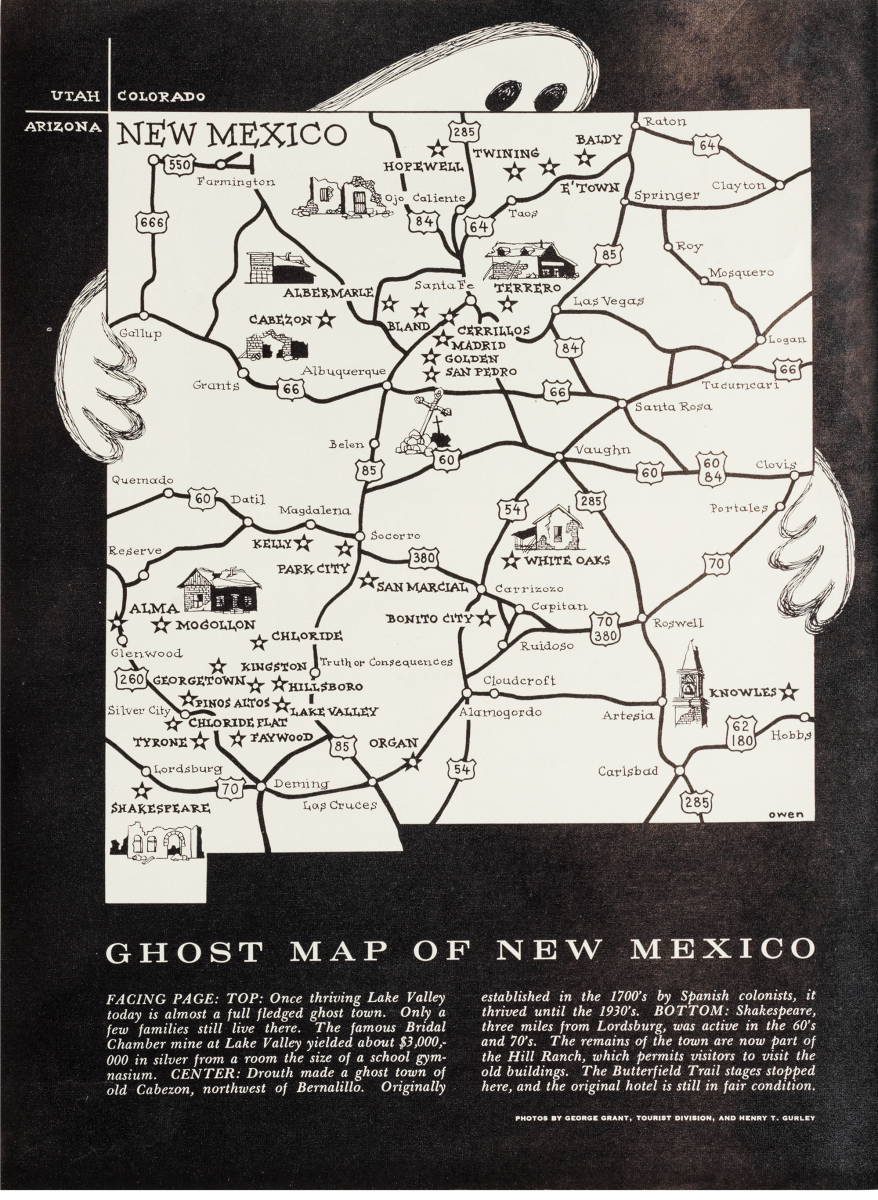

GHOSTS OF FRONTIER NEW MEXICO

REMNANTS OF A COLORFUL PAST are scattered throughout New Mexico in the ruins, or sometimes mere indications, of sites of towns, mining camps, and temporary settlements that flourished briefly.

Some of these places of the past have disappeared completely; others are ghost towns. In some cases, a few families still live where once hundreds and even thousands swarmed over the hills or the canyons to dig out silver and gold.

Many of today’s ghost towns were yesterday’s flourishing gold and silver mining camps. A few are just settlements that reached a peak and went downhill fast when the reason for their existence faded.

Some towns like Hillsboro and Cerrillos are not in the strictest sense ghost towns, for they have continued to exist as villages despite wholesale loss of population.

Shown on the map and in the pictures are some of the better-known ghosts of the past still standing, long after their reason for being has gone.—George Fitzpatrick