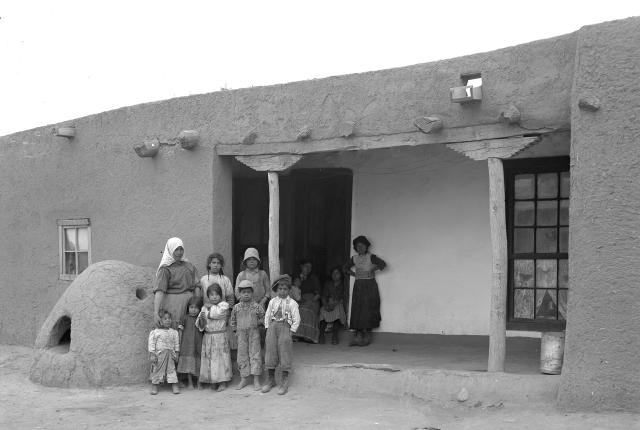

ARTISTS’ PAINTINGS AND OLD PHOTOS IN BOOKS capture the soft forms of adobe houses, melding like loaves of horno bread into the New Mexico landscape. Their scale and proportion in these depictions are balanced with their context and surroundings. They represent the uniqueness of the state’s architecture, cultures, and people. I am fortunate to have lived my life in homes constructed from adobe. There is something about a house built out of earthen materials that connects its inhabitants to la tierra sagrada, our sacred Mother Earth.

Since the 16th-century rumor of the Seven Cities of Cíbola—a legend that arose when the shimmering materials on a pueblo’s earth-plastered walls were mistaken for gold—the allure of adobe in New Mexico has persisted. People have been building with earth since humans began to construct their homes.

When I was growing up in the Embudo Valley, I heard stories of how the people’s agrarian lifestyle was sustained through acts of mutualismo, in which neighbors and relatives shared the labor for the construction and maintenance of their adobe homes. Women from the community worked as enjarradoras, going from house to house doing the plastering. The handprints I have discovered under layers of earthen plaster in my grandmother’s 200-year-old adobe walls cause me to wonder. Whose hands might they have belonged to, what conversations were had, and what songs were sung during the annual replastering?

I remember a time when some people who lived in homes built from adobe, vigas, and other traditional materials would long for a cinder-block, wood-frame, or mobile home. There was a stigma that one who lived in such a place could not afford a house built from modern materials. Then, in the early 1980s, I worked as an apprentice draftsman for a designer who specialized in high-end passive-solar custom adobe homes designed for wealthy clients around Santa Fe. By then, adobe construction had become expensive, and these clients were the only ones who could afford such homes. I began to appreciate adobe, and my insights were grounded in the houses of my upbringing.

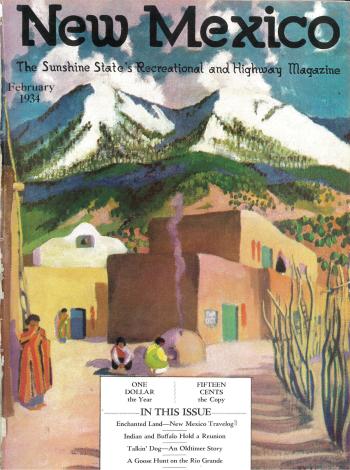

ON THE COVER

February 1934

Howard Patterson’s cover New Mexico Indian People coincided with the Philadelphia artist’s New Mexico visit.

In the late 1960s and early ’70s, after new building materials became more readily available, people began to abandon the adobe homes that had belonged to their families for generations. Seeing no value in these treasures, they began using them as storage spaces or demolished them altogether. I came from a family rich in tradition. My nearest relatives were great-aunts and great-uncles who lived in accordance with a time long gone—without the modern amenities of electricity, indoor plumbing, or propane heating. In my lifetime, I have witnessed the old world transform into the new. But I still feel more at home in the world of my antepasados. A world of familia, comunidad, respeto, humildad, y casitas de adobe.

While youth across the country were negating their parents’ traditions, young Chicanos—many of whom had returned home from college or the military during the Vietnam War—embraced the cultural traditions of their antepasados. They resisted assimilation and the modern lifestyles being introduced into the village. They preferred building their homes with adobe and heating with woodstoves or beehive fireplaces. They embraced the traditional manito way of life, not as historic preservationists but as people living their herencia.

Other young men and women from diverse backgrounds also began honing their skills as laborers and builders and eventually became recognized craftswomen and -men in the community. In addition, journals, books, classes, and workshops promoted earthen building design and construction. The counterculture youth who had settled in New Mexico adopted adobe as a favored building material for their crudely designed homes. These hippie houses are all but gone or renovated beyond their original semblance, but theirs was an aesthetic that borrowed from traditional adobe building methods and a regard for the nonconformist, off-the-grid lifestyles they found in the villages of northern New Mexico.

One does not need to be a professional or expert to make adobe houses. Anyone who knows how to wield a shovel, a trowel, and a level can more or less do it. Adobe is very forgiving.

Being from New Mexico, our relationship to the earth also filters into our identity in the world at large. At a poetry reading in East Harlem a few years ago, I introduced myself and my three friends from New Mexico who had traveled there with me as “mud-dwelling people.” That term comes from a story our Native American friend in the group recounts about the time when a delegation from his pueblo went to Washington, D.C., in the 1930s to petition for the return of lands that had been omitted from a U.S. government survey.

Having dinner one evening, they looked across the room and spotted a group of men at another table. “Look,” said one of the gentlemen to the others, “they’re dressed like us; they have haircuts like ours. They must also be mud-dwelling people doing business here in Washington. After we eat, we should go over and talk to them.”

When dinner ended, they walked across the room to greet the other men. As they approached, they were startled to realize that the other mud-dwelling people were their own reflections, shown in a large mirror on the wall. Mirrors were scarce at the pueblo, and they were not used to seeing themselves.

My introduction of my friends, by way of our connection to the earth, may have seemed strange to the audience in New York. But my friends and I, all from different backgrounds, had one thing in common. We all had grown up or lived in houses constructed from adobe. We were, after all, mud-dwelling people.

Levi Romero is an architect, a University of New Mexico associate professor of Chicana and Chicano studies, and New Mexico’s inaugural poet laureate.

OUR GEOLOGY ROCKS

“The Jemez Mountains are full of geological wonders, formed by many eruptions of New Mexico’s own supervolcano. The Valles Caldera National Preserve, which is one of the most beautiful landscapes in our state, is a giant volcanic crater created by an eruption that occurred 1.2 million years ago. Many of the dome-like hills within the caldera are all smaller, younger volcanoes, and the thermal activity is still apparent at the hot springs that dot the surrounding hills.”

—Nelia Dunbar, state geologist