JUSTIN PIOCHE (DINÉ) DIDN’T GROW UP EATING NATIVE FOODS, like blue corn mush with juniper ash or kneel-down bread. “I ate mac and cheese and Taco Bell,” he recalls. Now the Farmington resident and chef behind Pioche Food Group is on a mission to preserve and promote the traditional cuisine he missed out on as a kid.

At his eight-course LorAmy pop-up dinners, Pioche crafts modern interpretations of Indigenous dishes that highlight heirloom produce like amaranth and Hopi turquoise corn. In his Three Sisters dish, for example, squash blossoms are filled with a corn-and-bean ragout and topped with sunflower oil powder. Now it’s Pioche’s food that folks don’t want to miss—his creative approach and unique flavors earned the 36-year-old a nod as a 2023 James Beard Award finalist for Best Chef of the Southwest.

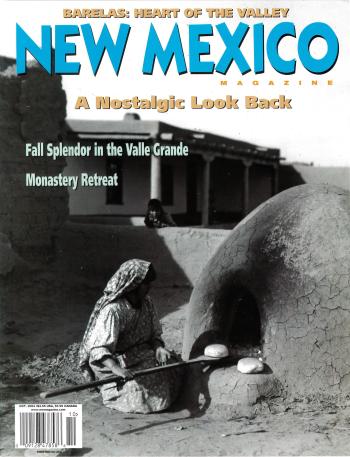

ON THE COVER

October 2004

“A woman bakes bread in the traditional way, using an adobe wood-fired horno at San Ildefonso Pueblo.”

ALL THE STORIES AND KNOWLEDGE I have been blessed to learn help me appreciate the history to tell the struggles my people have gone through. We serve a version of “bread of tears” (fry bread) at our dinners. During this course, I explain to our guests that this food represents our tenacity to live. From stories I’ve heard from the elders who lived through it, it goes back to when the government forced our people into prison camps and gave us rations of only canned foods, flour, lard, salt, and sugar—just enough to keep us from starving but not healthy.

I started LorAmy, whose name is a combination of my grandmas’ first names, to connect to my heritage and honor my people while utilizing my culinary training. That being said, my team and I love to cook what we like to eat—that’s where the modern techniques come into play. The dish at our pop-up that represents modern Native food the best is our version of neeshjizhii, or steamed corn stew. The flavors are traditional, but it looks nothing like a stew dish. We don’t serve the dish as a liquid. Every ingredient is separated and highlighted for flavor.

My family and I are passionate to pass on this knowledge to the youth, from cooking and seed planting to food preservation. If we don’t, it will be the end of our culture that makes New Mexico and the Southwest special.

I am proud to be able to represent my people and our culture. It’s great that our Native foodways are finally being recognized on a global level.

MAIN COURSE

Justin Pioche picks his favorite Native restaurants.

Juniper Coffee + Eatery. Pioche suggests the blue corn mush at this Farmington café. “They source a lot of their ingredients from Navajo-owned-and-operated businesses while promoting Native art in the dining area.” juniper-coffee-eatery.com

The Farmington Indian Center. “The cooks here use a lot of ingredients from Navajo Agricultural Products Industry,” he says. “The rotating mutton stews—like potato, squash, or hominy—are always great.” fmtn.org

The Indian Pueblo Kitchen. The restaurant serves up an unforgettable experience inside the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center, in Albuquerque. “They have awesome Pueblo bread and red chile stew,” he says. indianpueblokitchen.org

OUR WEAVINGS WARM YOUR HEART

"Chimayó weaving has been passed down for generations. It’s such an historical art form. It’s rooted in New Mexico, and it became Chimayó weaving specifically in northern New Mexico. You won’t find it anywhere else. It started out as utilitarian and now we’re branching into it as an art form. It’s beautiful, and in every piece you can see the people who made it and how they think. Chimayó weaving is a way of expressing yourself with geometrics and color.”

—Emily Trujillo, eighth-generation Chimayó weaver and teacher at Centinela Traditional Arts.