CŌLLETTE WAS BORN IN LAS CRUCES, and the Chihuahuan Desert environment influences her artistic practice. The Xicana artist of Indigenous descent uses crisp lines, meticulous detail, and warm colors (think orange, gold, burnt umber, and terracotta) to depict New Mexico flora and fauna. An oversize song sparrow sits on an agave bloom in the aesthetic treatment she designed for Las Cruces’ I-25/University Avenue interchange. In a similar project, for Williamsburg’s I-25 overpass, Cōllette portrayed a rattlesnake and a quail. For the New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs’ alphabet coloring book, Cōllette illustrated the letter Q with a quail. She worked a rattlesnake into the Monumental Loop’s identity mark and added a roadrunner and a centipede to the design on its official bike-frame bag. A roadrunner and a rabbit made their way into her public art commission at the New Mexico Department of Workforce Solutions’ Tiwa Building, in Albuquerque, and more work will be exhibited at the city’s Lapis Room in the fall. Her lips are sealed about a pending collaboration with an outdoors company.

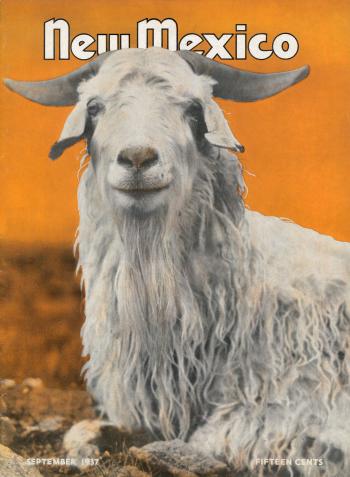

ON THE COVER

September 1937

A New Mexico goat stars in a shot by Wyatt Davis for this issue featuring “Shepherds on Horseback.”

I IDENTIFY AS MULTIRACIAL with Indigenous, Native, and Spanish ancestry. My grandfather carved objects from willow and pecan trees on his property, and also grew and painted gourds. My grandma nurtured our familia with food and encouraged my artistic talents by providing supplies and space to create. On their farm, my primos and I rode bikes, played in the ditches, caught tadpoles, chased chickens, climbed trees, made mud pies, and planted in the garden.

From third to sixth grade, I attended seven elementary schools in four states. I felt like I didn’t fit in anywhere. Those challenging years shaped who I am as a person and as an artist. My work is a reflection of different aspects of who I am. These aspects are visually communicated through imagery layered with personal symbolism of memories, emotions, dreams, my culture, or my sacred relationship with the land and its inhabitants. This relationship has played a significant role in my work since childhood.

Instead of including the state bird on the New Mexico Department of Transportation infrastructure in Las Cruces, I opted for the state reptile. The whiptail lizard is an all-female species that reproduces asexually through a process called parthenogenesis—a cool fact most people don’t know.

Animals and I have a mutual respect. Animals have a pureness to them. They are straightforward and easier to connect with than people. There were so many horny toads in this area when I was growing up; now you are lucky to spot one. The beloved roadrunner (aka el paisano and chaparral cock) is the badass of the bird world, because they prey on snakes and the tarantula hawk wasp. I just think javelina are super cute. My dearest animal companion of all is Pantera, my medium-haired black gato.

WILD ART

Explore how animals have served as subjects for art throughout the centuries.

Indian Pueblo Cultural Center. The Albuquerque museum’s Birds and Feathers exhibit explores winged creatures’ inclusion in pottery, clothing, and homes. indianpueblo.org

Petroglyph National Monument. A hundred petroglyphs, including a distinct macaw, can be seen on a walk at Boca Negra Canyon, in Albuquerque. nps.gov/petr/index.htm

A:shiwi A:wan Museum and Heritage Center. Learn about Zuni carved stone animal fetishes, which serve ceremonial purposes. ashiwi-museum.org

Western New Mexico University Museum. The Mimbres Mogollon people depicted deer, rabbits, lizards, and quail more than humans on their painted pottery, also integrating turkey feathers into geometric designs. “We see it as art but realize it’s a reflection of their worldview, environment, and culture,” says museum director Danielle Romero. museum.wnmu.edu