ALMOST ANYWHERE YOU LIVE IN NEW MEXICO, a mountain range rises within beckoning distance. Our major cities all stand in their shadows. Their names ring with poetry: the Sangre de Cristos, the Sacramentos, the Sandías, the Organs, the Mogollons.

If you put down roots here or count yourself among those whose roots go generations deep, you will develop an unreasoning love for a favorite mountain. Maybe you came to it young or in a certain mood or frame of mind. Perhaps it was love at first sight. Often you will choose not to profane the place by mentioning its name to outsiders. Let them find it on their own—if they can.

When I first saw the Gila Wilderness, I saw it from the top of a mountain. My friend worked the fire watch gig there, and she graciously shared the splendors of the place with me for a weekend. By the end of those three days, I didn’t want to leave. I mean really didn’t want to leave. She sensed this. So she worked a little magic and found a way to pass the job on to me.

I arrived there with a scarred soul. A brother’s suicide and a rather too intimate encounter with the destruction of the World Trade Center towers had left their marks on me. But in this landscape of hulking peaks, broken canyons, tilted mesas, and hidden springs, I felt something ancient and wild extend an invitation of healing. The wildness in your heart got you all twisted up? Come into the country and learn a thing or two about the dignity of wildness, the irrational beauty of it.

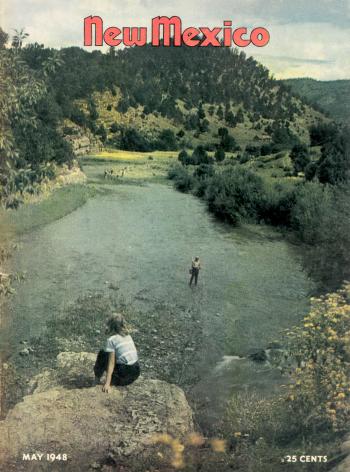

ON THE COVER

May 1948

J. J. Stienmetz captured this fishing picture just north of the Lisboa Springs Fish Hatchery on the Pecos River.

That was 21 years ago, right around the 78th birthday of the Gila Wilderness. This year marks its 99th. The Gila, as anyone who knows it will proudly tell you, is the birthplace of the wilderness idea put into actual practice: Take a piece of wild country and place it forever off-limits to new roads, or indeed any incursion from industrial machines, motorized or mechanized. Try to let it be what it wants to be, not what we would rather it be.

Twenty-one years of mountain sitting have made the place the center of meaning in my life. Chief among the experience’s joys are the fellow creatures and their mysterious habits, which grow less mysterious the longer one observes them.

What does the mountain want to be? A place where bears tear the bark off dead trees in search of army cutworm moths rich in lipids. Where short-horned lizards sun themselves on the rocks and dine on passing ants. Where Clark’s nutcrackers swing from limber pine branches like gymnasts on the uneven bars, pecking for seeds they then bury across the landscape in their version of a dispersed food pantry. Where ladybugs chase aphids. Where lichens drink fog.

I have been in conversation with the mountain long enough to have scattered a pinch of ash from two different friends who chose cremation as their final act. Their bone shards have joined with the ancient story of the mountain, a story that includes Native people who once gathered there to enact rituals and ceremonies, perhaps to be closer to the sky gods. Scattered potsherds testify to the sacred place the mountain held in their cosmology. The place hums with their energy still, a millennium later.

In my two decades there, I have seen the mountain buried in snow, deluged with rain, parched by drought, and engulfed in smoke. Some of my favorite old trees are now limbless, blackened spires, monuments to what was before the burn. It is deep and complex work to sort through the grief of that, when what’s been wounded and scarred is the very place that soothed my wounds and scars.

But for all it’s given me, I owe it my continuing attention at the very least. How will its scars heal? What does it want to be next?

If you fall in love with a mountain, you come to realize the love is as dynamic as the life that populates the place. Another way to say it: If you work on a mountain long enough, it works on you. And if you love it enough, you just might feel it love you back.

A fire lookout for 21 years in the Gila National Forest, Philip Connors is the author of three books: A Song for the River, All the Wrong Places, and Fire Season.