“THIS IS WHERE THE WORLD ROLLS UP,” Eric C. Brown proclaims from his Kingston Clay Company shop, perched on the edge of a town with barely 50 residents, 25 of them part-time. It sounds preposterous—if you believe the books and websites that have long characterized Kingston as a ghost town. Nestled in the Gila National Forest’s Black Range, roughly midway between Silver City and Truth or Consequences, Kingston and its neighbors, Hillsboro and Lake Valley, still bear scars of the boom times that went bust, but their beautiful seclusion draws a latter-day stream of people bursting with inventive spirit.

Here, where NM 152’s sheer cliffs, perilous turns, and lush valleys jackknife onto Kingston’s sleepy Main Street, Brown and his shop play a variety of roles. In a straw-bale studio out back, he crafts earthenware dishes, decorative urns for beloved pets that have passed on, and inventive wall pieces evoking his road trips. His shop is also one of the gathering points where local folks can share a cup of coffee, and he’s a lifeline for broken-down motorists and city folks spooked by bear sightings in the nearby campground.

Most travelers on the scenic route blast right through. Some pause for a night at Kingston’s Black Range Lodge, a few more enjoy a meal at the Hillsboro General Store Cafe, and maybe a couple of them also bag terrific Instagram trophies at Lake Valley Historic Townsite. The wise traveler, though, knows when to slow down and let the scenery sink in as the past meets a present brimming with alt-building projects, organic farms, off-the-beaten-track artists, and national-caliber music—a whole world, rolling up to their doors.

Nicki O'Dell serves up a taste at Hillsboro's Black Range Winery.

BLACK RANGE LODGE

Catherine Wanek and her partner, Gary Harvell, have spent the day prepping their 1880s-era Black Range Lodge for a weekend’s worth of guests. I’m the first to arrive, so I get my pick of rooms, along with a dose of Kingston history delivered by Wanek. Her three-story manor began as a brick-walled hotel for miners riding a silver boom and cavalrymen protecting them from displaced Apaches. The boom led to a thriving trio of towns with competing saloons, newspapers, brothels, banks, butchers, hotels, schools, outlaws, gamblers, one opera house, and just a hint of religion. It’s a lot smaller today, but, given the strength of the communities’ ties, it still adds up to the greater Kingston–Hillsboro–Lake Valley metroplex, with a total population of around 150, depending on the day of the week.

Altogether, the towns endured fires, floods, shootings, brawls, mines that went bust, and strikes that produced millions of 19th-century dollars. (Lake Valley’s Bridal Chamber alone yielded nearly $3 million worth of silver ore so pure that it skipped the smelter on its way to the mint.)

In 1893, the boom hit a bump when the U.S. switched to the gold standard and the price of silver plummeted. A bunch of buildings were dismantled, their parts carted to more promising towns—including Hillsboro, until its gold mines played out. The need for manganese during both world wars helped the region. In the 1930s, the Black Range Lodge grew larger, with handsome stone walls and viga-beamed ceilings. Ranches and farms thrived, with fields fed by the sometimes overexuberant Percha Creek. Wanek, a Las Cruces native who chased her writing career all the way to Hollywood before landing in Kingston back in the 1990s, outlines all of this as we pop into and out of quaintly comfy rooms sized for as few as one and as many as eight. (The one with kids’ bunk beds that you can close off from the main room holds particular charm.) Many of them boast balconies for beholding Wanek and Harvell’s permaculture herb garden, heirloom fruit trees, and free-range chickens, an open-air performance stage, his massage house, and the cluster of buildings crafted by participants in her eco-building workshops.

“The lodge itself is a natural building of stones, logs, and bricks,” says Wanek, who’s written several books on sustainable construction. “I’ve gradually fixed it up with the idea of retaining its character while improving creature comforts. So we have a natural classroom, a straw-bale greenhouse, a free-form ‘hobbit house,’ and a ‘truth wall’ that shows all the types of building materials we use—even wine bottles.”

Massive gathering spaces inside the lodge are lined with bookshelves, warmed by fireplaces, and graced by cozy sofas, plus a pool table. Hiking trails into the Black Range Mountains begin within a half-block stroll from the front yard. Wild turkeys, deer, and javelinas wander through. Families hold reunions, brides and grooms say their vows, and cross-continental cyclists traveling from California to Florida rest up after cresting the journey’s 8,828-foot high point, nearby Emory Pass.

A few years ago, Wanek and Harvell began hosting a summer-through-fall series of “Starlight Concerts,” comprising Americana, Native American, and bluegrass and including performers lured from the music capital of Austin, Texas. This month, they introduce Banjo Camp, an addition to their longer-running Desert Night Acoustic Music Camp for adults, offered each October.

“That’s our favorite thing,” Wanek says of the camps, for which nearly 50 musicians come. “The people are happy, there’s music flowing out of every room, they have jams every night.”

I settle on a room with a secluded balcony and big windows framing misty blue mountains. I fall asleep, dreaming of a lonely fiddle tune.

The exterior of Lake Valley's schoolhouse turned museum.

LAKE VALLEY HISTORIC TOWNSITE

Bureau of Land Management archaeologist Jennifer Frederick guides me along the Geronimo Trail Scenic Byway. Our goal: Lake Valley Historic Townsite, about 16 miles south of Hillsboro. It’s a certifiable ghost town with intact buildings and just two residents—“volunteers who get excited about history,” Frederick says. The hosts rotate in and out. Frederick and I meet up with Penny and Russell Phillippi, retirees who’ve taken other watchdog stints in Florida, California, and Alaska but adore having fruit trees outside their Lake Valley RV and a steady stream of visitors—all carrying cameras.

“You can’t believe the sky drama here,” Penny says. “And cattle drives go through here. It’s so beautiful.”

We stand in the old one-room schoolhouse. The BLM, which owns most of the townsite and a lot of the 300 abandoned mines dating back to 1878, turned it into a museum. Before that, NMSU students from the 1970s through the 1990s came up for dances so popular that dust rose from the weathered wood floor. (During one dance, the bell disappeared; an anonymous donor returned it in 2000.) Sometimes, Penny says, local rancher ladies hold tea parties in the school, and folks with a family tie to the town ponder the past in the restored chapel up the way or visit the dearly departed in the cemetery off the main road.

In between lie buildings in various states of ruin, a trash heap of old tin cans and a different one of old bottles, and the blocked-off entrances to the mines—including the Bridal Chamber, which was purposely collapsed after the silver played out. With Frederick’s okay, Russell unlocks some of the usually off-limits areas—buildings filled with tempting artifacts and trails that cross private property before reaching more ruins. A metal Conoco sign squeaks in a wind that, Frederick says, “is like its own character out here.” That wind fed disastrous fires in the silver days. Penny has found bits of molten glass in the rubble, and it all inspires her to imagine the people who occupied houses and hotels, who worked the mines and made the food, who taught the children and saved the souls. “You walk out there and you can touch all the lives,” she says. “So much life.”

Names are attached to some of the lives. John Miller was the sorry storekeeper who sold his mining claim to a group of investors who promptly discovered the Bridal Chamber. The Sierra Grande Mining Company included among its stockholders poet Walt Whitman, who received only a fraction of the dividends he was due. (In 1902, a London court convicted owner J. Whitaker Wright of stock fraud; he promptly swallowed a lethal dose of cyanide.) Then there was Sadie Orchard, who purportedly owned all the brothels in the tri-town area and fancied herself an upper-crust Brit, although her accent fell somewhere between Cockney and fake.

Most accounts say Lake Valley’s population peaked at 1,000. (The BLM says 4,000.) But even after the crash, people in Hillsboro and Kingston needed a place to shop and buy gas, so it sputtered along. The last two residents moved away in 1994. A winter wind whips around us as Penny and I gaze past a wasted car of rounded-fender vintage toward Monument Peak, a barren cone topped by a craggy knob. The sense of shrinking into a void so effectively envelops us that I have to ask if she ever gets spooked.

“We keep the ghosts under control,” she says with a laugh. “There’s not been any freaky, crazy stuff. I don’t feel isolated. I feel like God loves me.”

The interior of the old Lake Valley School.

HILLSBORO

I wake to the crisp aroma of mountain air spiked with a bouquet of bacon. Downstairs, Harvell commands the lodge’s 110-year-old Garland stove—“the same kind Julia Child had,” he says. Breakfast is part of the package. No lunch, no dinner, and nowhere in Kingston to buy it, so he and Wanek let lodgers bring their own food and use the kitchen. But who needs another meal after eggs-any-way-you-want, bacon, sausage, granola, yogurt, pancakes with real maple syrup, OJ, and bread so fresh from the oven that it appears with a wisp of steam?

“Did we mention we grind our own organic grains?” Harvell says.

They also buy their coffee beans from Just Coffee, a grower-owned cooperative in Chiapas, and have so decisively addicted their neighbors to it that they had to create a sub-cooperative to share each purchase. Like everyone else in the metroplex, they rely on shopping trips to Truth or Consequences, supplemented by occasional ones to Albuquerque or Las Cruces, plus shipments by mail. And everyone shares what they can. “We all feel like neighbors, even though we might be 30 miles apart,” Wanek says. “We might be on the opposite side of politics, but if we think we’re going to disagree, we let that topic lie.”

Squabbles do erupt. Ted Turner’s massive Ladder Ranch supports wolf-reintroduction efforts that many local ranchers despise. A mining company hopes to restart the Copper Flat open-pit mine in the Hillsboro Historic District. Some folks ache for the jobs it might bring; others fear the environmental cost. And local historians argue endlessly about where the legends meet the truth. I’m about to get a taste of that, thanks to Wanek inviting the Albuquerque-based Earthbuilders Guild to Hillsboro, a nine-mile drive west.

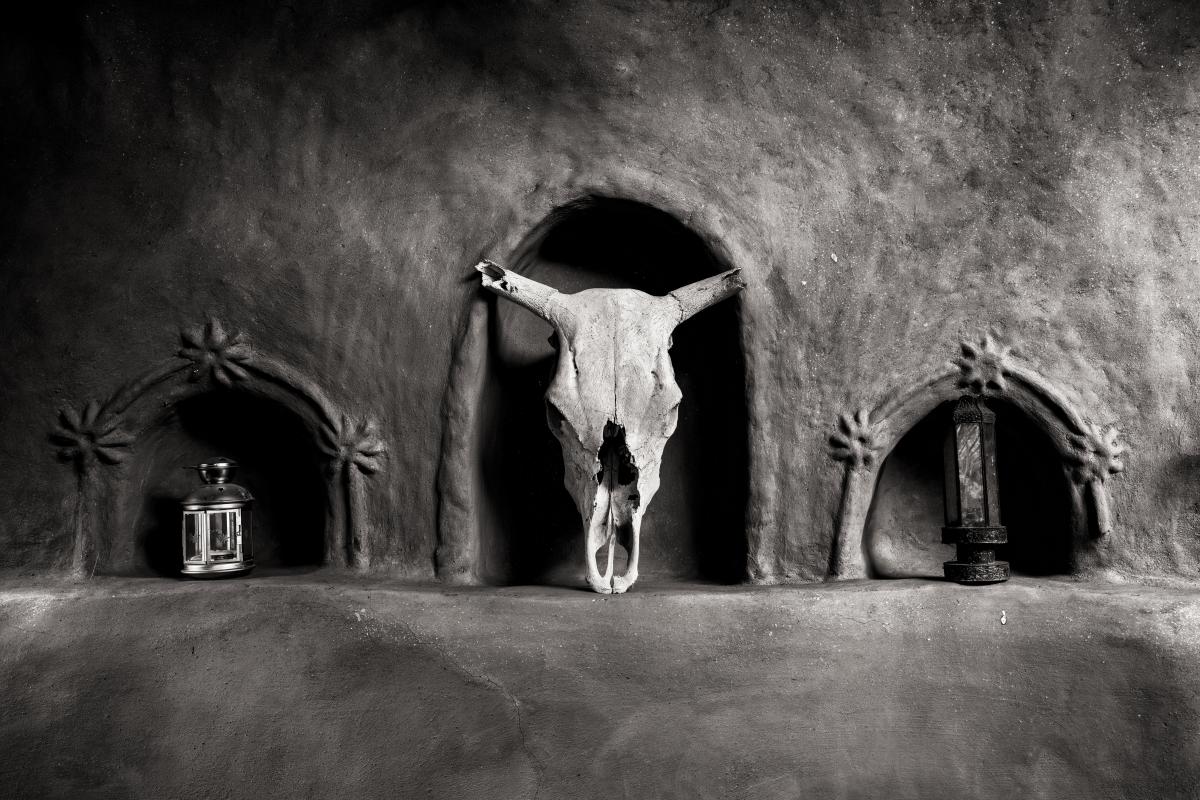

Inside the Black Range Lodge.

We meet in front of the Black Range Museum, where historian Garland Bills explains the extensive renovation project on what long ago was Tom Ying’s restaurant, part of Sadie Orchard’s Ocean Grove Hotel. Even Bills acknowledges the question marks. Was it a brothel or just a hotel? Did Orchard own the eatery or was it Ying’s? “We got our info from the people who had this museum before, and we’re not any better than they were on the facts,” he says.

Long run as a grandma’s-attic kind of museum, the building was snapped up by the Hillsboro Historical Society in 2016, and its members have diligently raised money and scoured public records to shore up its walls as well as its facts. On this day, the roof is mostly missing. Alder and pine vigas sit stacked, waiting to be reused. Some of the adobe walls have been carefully patched. As soon as possible, the museum will reopen. In the meantime, we stroll out back and marvel at the reconstruction of an adobe water tower that delivers a steady stream through the miracle of gravity.

We walk around town, noting the architectural styles of various eras, then pause at the old Sierra County Courthouse. Before Hillsboro shrank and T or C grew, the former was the county seat; now it’s the latter. Orchard filed a lawsuit against the move. She lost. The once stately courthouse, with its tall, arched windows, is but a skeleton—a few brick walls hint at its three-story glory. The red-rock jail behind looks better, thanks to its iron doors and barred windows. Still, mesquite trees and cacti thrive within and around it.

Bills tells stories of early residents, including the sheriff who tried to save his wife during one of Percha Creek’s awful floods. She was safe on the second floor of a Main Street building where she was attending an Eastern Star meeting; his body was found downstream, 50 feet above the creek. But the old tales start to pale next to the new ones. We pass a house owned by the retired dean of divinity from an Ivy League school. A biology professor back East owns another one but opens it to biology students researching wildlife on the Ladder Ranch. Former Lieutenant Governor Diane Denish has a house here. Bills was a UNM linguist before retiring in 2003 to a 75-acre spread on the larger Lake Valley Ranch.

So it’s true: The world really does roll up. But why? “For me, it was the isolation, the wildlife, the stars—not the town,” says Bills, whose wife passed away three years after their move. “Now the town has become sort of my second life. People here are great.”

The Percha Bank, in Kingston.

During lunch at the Hillsboro General Store Cafe, I get a serving of that community spirit, along with a bowl of beans swimming in sinfully rich red chile. It’s the only place to eat—breakfast and lunch, no dinner—and the best hub for catching up on how everyone’s doing, who needs a hand, and who deserves some sass from owner Ben Lewis. “I make up rules on who can order what, just because I like to play with people,” he says. He hails from Texas, and his wife, Doreen, is from Winnipeg, Canada, where they were living when the cold got too deep in their bones. While puttering around the Southwest in 1995, they saw a for sale ad and—bam—bought a café. “It’s one of the most questionable decisions I’ve ever made in my life,” Ben says, and he’s only half joking.

They had to reno the 1879 adobe, a former pharmacy, which lacked square corners and level floors. They ended up with a long, narrow eating area surrounded by wooden cases filled with drugstore memorabilia. Other antiques occupy every wall, including a 10-foot-long python skin that has hung on the wall longer than even old-timers can remember. “We just painted around it,” Ben says.

He likes living 15 seconds away from work and keeping the hours manageable. Monday through Wednesday, he drives mail for the U.S. Postal Service, from Deming to Columbus and Hillsboro. But 24 years after a snap decision, he admits, “We’re in it to sell it. We want to go play with the grandkids.” He’s looking for a special breed of buyer. “It’s not buying an investment,” he says. “It’s adopting a community.”

On fair-weather Saturdays, some of that community shows up on street corners to play music. Cindy Yarmal sells organic produce from her Animas Creek Honey and Herb Farm at the one-woman farmers’ market. Throughout the week, a few shops sell assorted antiques, crafts, and cowboy gear. If you play nice, you might score an invitation to the potluck at the Black Range Winery, a few steps down from the café.

Brian and Nicki O’Dell planted grapevines in 2007, renovated their house, and then turned their storefront into a tasting room, art gallery, and performance space, mainly because she “wanted a place to hang out, eat, drink, and listen to music.” Now they sell and serve tastings of their wines, including El Gallo Loco, a chile-infused red, plus a few craft beers. Nicki invites me, and I behold a stream of neighbors with casseroles and salads as Brian lays down platters of fresh-smoked brisket. Leah Tookey, a curator at the New Mexico Farm & Ranch Heritage Museum, in Las Cruces, pulls up a chair and tells me how she plans to feature Black Range wines in her Meet the Producers exhibition. She’s another part of the world that rolled up. “I just wandered in one weekend and fell in love with Hillsboro.” She thereupon parked a trailer, long-term, in the Hillsboro RV Village. “You just fall in love with these people,” she says.

Ike Wilton of the Hillsboro Tradin' Post.

KINGSTON

The next day, historian Barb Lovell bundles me onto her Kubota to scoot all around Kingston. We blow a good hour inside the one-room Kingston Schoolhouse Museum, poring over documents and photographs. The Spit & Whittle Club (namely, everyone in town) meets here monthly. It used to be one of many social clubs when Kingston’s population topped out at 1,500—or 5,000, depending on whose story you buy. They had the Excelsoire Society, Knights of Pythius, Grand Army of the Republic, and the Spit & Whittle, which sensibly advised members, “Never spit into the wind and always whittle away from yourself.” Lovell pulls up copies of articles from the Kingston Weekly Shaft, Kingston Miner, Sierra County Democrat, Kingston Ledge, and Sierra County Enterprise. “Even the ads are fun to read,” she says. “They advertised from as far away as Boston and Juárez.”

Local ads promote saloons, hotels, and mining claims, but not Sadie Orchard’s girls. You could make a case for their being part of the mythos. Garland Bills says he presumes the legend is true only because Orchard chose to live with her soiled-dove reputation. Plus, the rooms in her Hillsboro hotel do seem rather small. Lovell, a retiree who helped her husband renovate a run-down Kingston house for getaways from their Fort Garland, Colorado, home two years ago, oversees the museum and scrutinizes any written record she can find in county offices, at archives, and on the web. “There’s so much out there that’s wrong,” she says. “But I’m not done.”

We visit the old cemetery, then ask Gary Harvell to open the Percha Bank Museum, which Catherine Wanek’s mother owns, to marvel at its ornately painted safe. We tool along the main drag, with Lovell laying out each building’s history, even if the building is gone. We end up at Kingston Antiques & Art, a shop she recently opened. Jeweler William Lindenau, whose work is on display, happens to be there, and he explains how he left the crowded Bay Area in 1999, seeking seclusion. He and his wife built a straw-bale house on Virtue Street, near one of Orchard’s supposed bordellos, after attending a workshop at the lodge. Other artists pepper the hills, but ghosts are hard to find.

Lovell says the facts are fascinating enough to satisfy her, along with the company of all the living folks. Brown welcomes them at his clay shop, which advertises out front that it’s also a coffee shop. “That’s more for the neighbors,” he says. “They come over and we hang out and chat.” After a ceramics career in Las Cruces, the upstate New Yorker moved to Kingston because he liked the vibe at the lodge, enjoyed jamming with other musicians, grooved on mountain living, and loved the local clay.

Leaning across a table, his fringed leather vest topped by the long curls of his hair, he talks about the cars he’s fixed, the bicycle tires he’s refilled, and the RVs he’s put back on the road. “You always carry five gallons of gas and tools if you live here,” he says. “Some of the places I might live, people would look at me like I’m a long-haired hippie freak, but here I’m the guy you call for help.”

He sings the praises of this neighbor and then that one, slips in a little gossip, and concludes with what might as well be the motto for people who live in a supposed ghost town where the world rolls up: “We all love each other,” he says, “whether we like each other or not.”

HITTING THE HAUNTS

Choose your HQ: the Hillsboro RV Village; a National Forest Service campground in Kingston; the Enchanted Villa Bed and Breakfast, in Hillsboro; or the historic Black Range Lodge, in Kingston.

Brochures and signage help with self-guided tours at Lake Valley Historic Townsite. Bring your camera, binoculars, and a picnic lunch. Open 9 a.m.–4 p.m., Thursday through Monday; admission is free. Learn more at nmmag.us/lakevalley.

The Hillsboro Historical Society has brochures with a walking tour of the town. Download a simplified version at nmmag.us/hillsborotour. Most action lies within three blocks: breakfast and lunch at the Hillsboro General Store Cafe; wine tastings and an art gallery at Black Range Vineyards and Winery; and a few small shops, including the Hillsboro Tradin’ Post. Get set for the reopening of the Black Range Museum. Learn about Kingston’s history and download a walking-tour map at nmmag.us/kingstontour.

The Kingston Schoolhouse Museum is open 11 a.m.–3 p.m. on each month’s first and third Saturday, or by appointment (575-895-5011). To see the Percha Bank Museum, ask at the lodge. Plan a hike into the Gila National Forest or shop at Kingston Antiques & Art and the Kingston Clay Company.