The adobe-walled Cleveland Roller Mill is one of the three historic flour mills that remain today.

TWENTY-FIVE MILES NORTH OF LAS VEGAS, a gentle giant of a building welcomes drivers to a pastoral valley where the present keeps close company with the past.

A metal waterwheel straddles the rushing spring waters of the Mora River. Beyond it, a path winds around a wonky complex of adobe buildings with faded blue shutters. Whether you walk the grounds of the La Cueva Mill in the clear light of morning, looking to the high eastern plains, or in the lengthening afternoon shadows of the surrounding mountains, the old gristmill feels like a wannabe time traveler’s dream destination.

The 150-year-old former flour mill, near La Cueva Farm’s raspberry fields, is more than an architectural tribute to the lasting marriage of Spanish construction and American engineering. Its metal gabled roof and earthen bricks represent the remnants of a densely grouped milling system that once nurtured a wheat-growing region known as “the bread basket of New Mexico.”

Along a seven-mile stretch of the river, from La Cueva to Cleveland, three historic flour mills remain: La Cueva Mill, St. Vrain Mill, and the Cleveland Roller Mill, now a museum. Thanks to preservation efforts by local residents, this scenic drive is a journey through the little valley that, at one time, could. Its people built seven mills in as many miles, supported crops that fed people far beyond their mountain borders, and protected the resources and lifeways of a place some New Mexicans call “God’s country.”

The Cleveland Roller Mill is now a museum.

These days, there’s a new mill. Built in 2003, the Mora Valley Spinning Mill sits in the heart of downtown Mora, breathing new life into the tradition of local wool spinning and weaving.

“That spirit of self-sufficiency was already there before the mills,” says A. Gabriel Meléndez, a Mora Valley native and a University of New Mexico distinguished professor. A vibrancy existed even before Ceran St. Vrain built the valley’s oldest standing industrial mill, in 1864, to supply a $41,000 flour contract with Fort Union, Meléndez says.

“It was remarkably diverse, although on a small scale,” he says. “You had Syrian and Lebanese merchants. There were Jewish merchants and Anglo-Americans and Irish soldiers. St. Vrain, coming from back east, arrives in the 1830s and intermarries with the local community.”

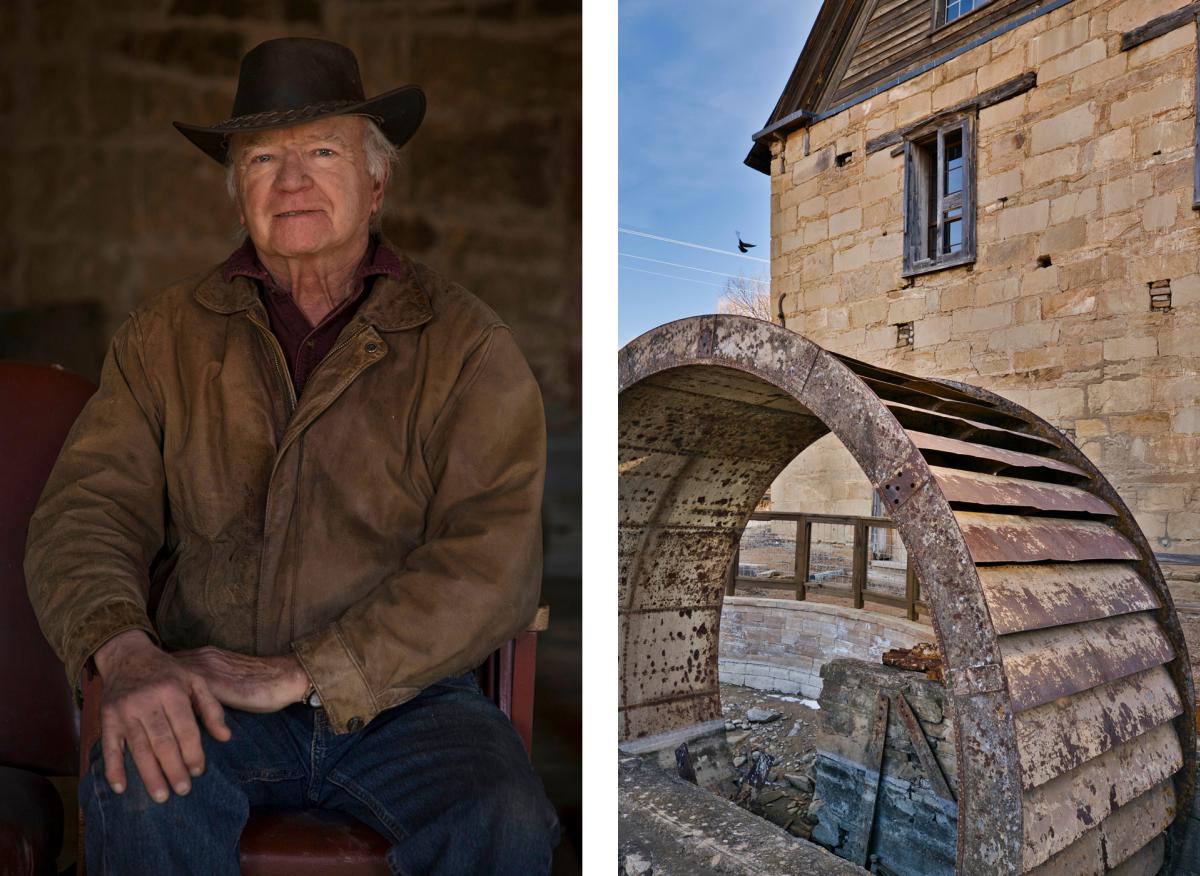

Merlyn Witt at the St. Vrain Mill (left) and its waterwheel (right).

Merlyn Witt at the St. Vrain Mill (left) and its waterwheel (right).

The mix was rounded out by French priests who established Christian Brothers schools, Italian Jesuits who came from Las Vegas, and Spanish-speaking farmers, herdsmen, and ranchers. The Mora Valley economy was boosted by booming wheat crops, cattle and sheep ranches, and the increasing consumer demands from nearby forts and cities like Las Vegas, Taos, and Santa Fe.

All had reason to hail the rise of the local gristmills that processed grain from the 1860s to the 1940s. In The Book of Archives and Other Stories from the Mora Valley, New Mexico, Meléndez writes that a local politician gave a speech at the inauguration of the La Cueva Mill, where farmers mingled with priests and politicos, and women dressed in their Sunday best. “People of Mora County, here before you are the fruits of American genius,” the tax assessor proclaimed, before referencing a traditional hand-grinding tool. “The metate,” he said, “gives way to Yankee ingenuity.”

The St. Vrain Mill interior used to bustle with wheat grinding.

The St. Vrain Mill interior used to bustle with wheat grinding.

INSIDE THE THREE-STORY ST. VRAIN MILL, traces of that ingenuity abound. Merlyn Witt, president of the St. Vrain Mill Preservation and Historical Foundation, points to a column on the first floor. The wood bears old scratches revealing decades of milling calculations as well as “I was here” inscriptions. “ ‘Guadalupe Romero, May 15, ’96’—that’s not nineteen ninety-six,” Witt says. “That’s the oldest one I’ve found.”

The foundation, which purchased the mill in 2015, has made considerable headway in restoring windows, gables, and the second-story loading platform. Witt says repairs to the walls are the next—and most expensive, at an estimated cost of $125,000—task of the foundation, which plans to open the first floor to visitors after Memorial Day. The goal is to repurpose it into the Mora Valley Heritage Center, with a meeting space, and to feature exhibits on the history of generational families in the area. In recent years, the refurbished St. Vrain has hosted quilt shows and a pop-up Christmas arts-and-crafts fair.

Vice President Betsy Bloch says there is no shortage of interest in goings-on at the mill. “People are very proud of their heritage here and they want to revive it,” she says. “If we’re here for more than 20 minutes, someone will stop and get out of their car and come in and say, ‘Oh, I’ve always wanted to go in here.’ ”

An old truck sits on the grounds of the Cleveland Roller Mill (left), which is owned by Dan Cassidy IV (right).

An old truck sits on the grounds of the Cleveland Roller Mill (left), which is owned by Dan Cassidy IV (right).

A few miles down NM 518, Cleveland Roller Mill Museum owner Dan Cassidy IV says that although the pandemic has closed the mill for now, he never minds the respectful road-trippers who get out to take awestruck looks around the grounds. Cassidy’s great-grandfather Dan bought the 1890s-era mill in 1913 and ran it as a family operation into the mid-1940s, after the majority of the more than 200 mills statewide had already closed, victims of advances in milling technology and the Dust Bowl’s pummeling of farmers. (Valencia Flour Mill, in Jarales, and Navajo Pride Flour Mill, in Farmington, appear to be the only operational wheat mills left in New Mexico.)

Cassidy says his family’s mill, which became a private museum in 1989, was a 24-hour operation in the late 1920s and ’30s, producing up to 50 barrels of flour a day. With evident pride, he adds that the Cleveland Roller Mill had state-of-the-art technology for its day. “The other mills have stone-ground wheels,” he says. “They never had all this elaborate sifting machinery, so they could only do the most basic stone-ground flour. But this one could separate all the way down to white and pancake flour, to three or four different products.”

All the original machinery, bought as a turnkey operation from industrial manufacturers in Kansas and Pennsylvania, is still installed in the Cleveland Roller Mill. A few wood panels here, too, bear the traces of old production calculations. Since 1987, Cassidy has drawn musicians, craftspeople, and visitors to the Cleveland Millfest every Labor Day weekend to demonstrate the milling process and run the waterwheel. He gestures toward an old yellow Ford truck sitting outside the mill. “This mill is just like a Model T. All the new cars are much fancier, but they have the same basic engine. So does this flour mill.”

The Mora Valley Spinning Mill's nonprofit weavers' gallery features work by local artisans.

The Mora Valley Spinning Mill's nonprofit weavers' gallery features work by local artisans.

OVER AT THE MORA VALLEY SPINNING MILL, mill manager Daryll Encinias explains that, unlike the historic flour mills, “this mill has not been here forever. But the farmers and sheepherders who provide our wool have been working here for a very, very long time.”

The spinning mill, along with its nonprofit weavers’ gallery, Tapetes de Lana, which features work by dozens of local artisans, was sponsored by economic development grants that aimed to extend spinning and weaving traditions in the Mora Valley. Encinias says the wool mill has grown into one of the largest industrial spinners in the West. He and his team process fibers ranging from churro sheep to alpaca, yak, and camel.

Encinias walks me through the wool mill, explaining the weeklong process that transforms 100 pounds of raw churro wool into 60 pounds of cleaned and finely spun yarn for weavers. Running my hands over the ancient industrial machines and the lanolin-coated puffs of uncleaned fibers, I marvel at the little valley with the uncommonly good memory of its own history.

Theresa Olivas (left) draws national praise for her tamale business. Get them to go and you can gussy them up to your family's pleasure (right).

Meléndez writes that his homeland is filled with a masa madre, a regenerative yeast that sustains itself on its own traditions and stories. “Memory is powerful as a means to collect and hold things for other generations, but it is dead if the everlasting yeast of imagination fades and dries up,” he explains. An industrious and imaginative hope springs eternal here—powered, it seems, by the Mora River.

MILL AROUND

Fruits of the valley. Where NM 518 and NM 442 meet, picnic benches and an adobe-walled garden on the La Cueva Mill grounds offer prime real estate for a picnic lunch. In late summer, hit the U-pick raspberry fields at the adjoining La Cueva Farm. The farm’s Mill Café serves barbecue, sandwiches, and raspberry sundaes. Seasonal hours.

Fruits of the loom. Tapetes de Lana, at the intersection of NM 518 and NM 434, serves as the unofficial welcome center to Mora. Browse yarns from the Mora Valley Spinning Mill, plus weavings, pottery, quilts, and soaps from more than 90 local makers.

Grist on the mills. Learn about the Cleveland Roller Mill Museum at clevelandrollermillmuseum.org, and the St. Vrain Mill’s renovation at stvrainmill.org.

Top tamales. Even The New York Times couldn’t resist the siren song of Teresa’s Tamales, which have been rightfully famous across the Mora Valley since the 1990s. Don’t miss the red-chile-and-pork masa missiles at this tiny treasure right off the highway; order a day in advance for green-chile-chicken or calabacitas tamales. 3296 NM 518, Cleveland; 575-387-2754.

Farm stay. Find off-grid serenity in the guest cabins at Los Vallecitos, a working ranch at the base of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Certified grass-fed beef and lamb are for sale here and at Los de Mora Local Growers’ Cooperative, in Mora. From $55 a night.

Read More: Following the strands of New Mexico's staunch weaving traditions, from sheep to shop.

Read More: Las Vegas is the gateway to the lush, rustic Mora Valley.