LAS VEGAS IS ESSENTIALLY A TALE OF TWO TOWNS—Old and New, West and East—that separately incorporated in 1888 and 1903, respectively, and did not join as one municipality until 1970. Similarly, the present-day Plaza Hotel, situated in the heart of Old Town, is really a story of two buildings.

Side by side, the ornate Italianate facades of the Plaza Hotel and the Charles Ilfeld Building have elegantly presided over the Las Vegas Plaza’s northwest corner since 1882. “Many people consider this the best Victorian Italianate building in the Southwest,” says Allan Affeldt, who bought the hotel in 2014.

The fortunes of the two structures have always been intertwined, but in 2006, a marriage was made official when a $6.8 million renovation (before a generous historic preservation state tax credit) added an annex between the buildings. The hotel gained 35 guest rooms and the Charles Ilfeld Building’s grand ballroom and meeting space. Today, each room is outfitted with a placard honoring the hotel’s many celebrity visitors, from Michelle Obama to Doc Holliday. Although guest lodgings in each building have their own distinctive character, there is a unique harmony of purpose in the new union between the two stately structures.

Built by a consortium of businessmen—a mix of local Hispanos and European immigrants—led by Don Benigno Romero, the Plaza Hotel arose from a collective desire to give Old Town a first-class hotel. Visitors from all over the world were newly disembarking from the three-year-old Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway station, located across the Gallinas River, a little more than a mile from the plaza. At the then newly built guesthouse, they would enjoy the finest comforts of the Gilded Age, including a dining room called the Plaza Supper Club overlooking Plaza Park, two retail spaces, and a spacious dance hall.

MEET ROMAINE FIELDING

The flamboyant filmmaker leased the entire Plaza Hotel in 1913. The west wall still bears the remnants of his brief rebrand, “Hotel Romaine.” The first airplane in the area did aerial stunts in one of the movies he made all around town, most of which are lost to the ages.

In the three years leading up to the hotel’s opening, Las Vegas had become a notoriously lawless town, dubbed the “Wildest of the Wild West.” Heavy hitters who passed through and made their mark include saloon keeper and crime boss Vicente Silva, Pat Garrett, Billy the Kid, and Doc Holliday, who arrived just ahead of the railroad and briefly operated a dental practice before he ditched it to open a saloon and gambling hall. (He also committed at least one murder during his stay.) Robert Ford, fresh from assassinating Jesse James and bragging about the deed to anyone who’d listen, ran a bar on Bridge Street before he fled to Cerrillos, having been humiliated in a shooting contest. The group that built the Plaza Hotel hoped the imposing new “Belle of the Southwest,” as the lodgings were known throughout the Territory, might establish some order and grace upon the place.

Elmo Baca, who bought and renovated an 1884 Italianate storefront (now the Indigo Theater) on Bridge Street in 1980, says the red-brick Plaza Hotel is inspired by the kind of palazzo you see in Florence, Italy. With few trained American architects in the years following the Civil War, “the Victorian era was characterized by an eclectic mixture,” he says. In replacing the previous two-story Territorial-style adobe Las Vegas Hotel, architect Charles Wheelock looked to Europe for inspiration, outfitting the state-of-the-art landmark with cast-iron columns, window pediments, and a commandingly ornamental broken pediment that crowns the roof.

BROKEN PEDIMENT

The white triangular ornament that soars at two angles over the Plaza Hotel is found in classical architecture and its influences.

GERMAN IMMIGRANT CHARLES ILFELD’S ambitious three-tiered Great Emporium—one of the West’s very first department stores—went up quickly beside the Plaza Hotel. The new brownstone replaced Ilfeld’s adobe business on the north side of the plaza, and its sales floors offered customers everything from groceries to dresses to carpet.

The dignified sandstone walls and brownstone details are complemented by plate-glass display windows and bracketed hood windows above. In 1890, the building was enlarged with five additional bays. Harvey Kaplan, a member of the state Historic Preservation Division, says the Ilfeld Building has weathered the past 139 years better than brownstones like it in the East. “The first time I looked at it up close, I was stunned because it still has chisel marks from the mason who cut the stone.”

MEET CHARLES ILFELD

When the German-Jewish immigrant arrived in New Mexico in 1865, he’s said to have had only five dollars to his name. Less than 10 years later, the merchant led the largest mercantile company in

the region.

The two buildings sat empty for much of the late 20th century before they were renovated and reopened. At this year’s Fiestas de Las Vegas, in July, the fraternal Victorian buildings loomed as dual sentries over a dancing hometown crowd in Plaza Park.

Kaplan considers even the buildings’ past neglect to be part of their triumph. “When the economic climate drops in a place, sometimes there’s no urban renewal money to tear buildings down,” he explains. “They may be boarded up, but they’re still there. Then you get these incredible survival stories, just like in Las Vegas.”

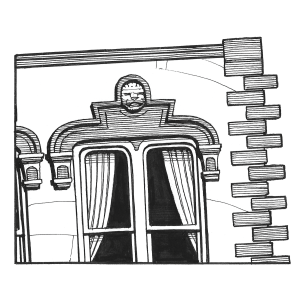

PROJECTING CORNICE

The Ilfeld Building’s ornamental stone-lion cornices stick out above its windows, throwing rainwater clear.