BENEATH THE CRAGGY SPIRES of the Organ Mountains, rumors of hidden gold still drift through piñon-juniper canyons near Las Cruces. For at least 150 years, the legend of the Lost Padre Mine has lured prospectors, hikers, and history buffs—a tale of vanished treasure, buried faith, and the enduring pull of the Southwest.

As the story goes, French priest Felipe La Rue was stationed at a mission in Chihuahua, Mexico, in 1797, and befriended an aging Spanish soldier. In gratitude for the padre’s care, the soldier revealed the location of a secret gold mine hidden between two peaks in the Organ Mountains.

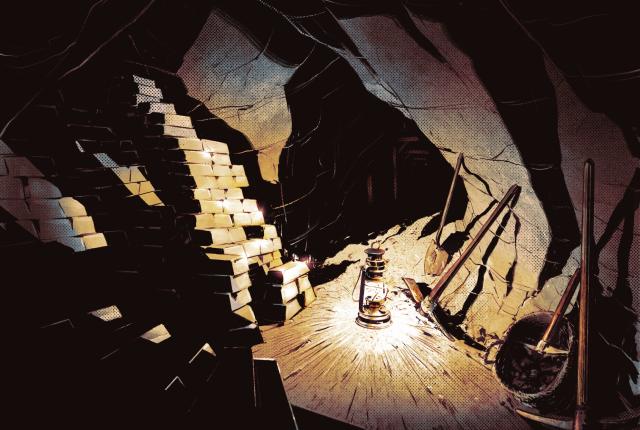

La Rue and a group of mission laborers soon abandoned their post, tracked down the vein, and began smelting ingots in secret. For several years, they worked quietly, concealing the mine from colonial and church authorities. When word of the mine eventually reached Mexico City, officials demanded La Rue surrender the treasure. The priest refused. Instead, he ordered the shaft sealed with tons of red earth—erasing both the mine and his fate from the record.

“New Mexico has had treasure stories from the very beginning,” says historian Don Bullis, noting the tales of the Seven Cities of Cíbola that drew Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca and Francisco Vázquez de Coronado in the 1500s. “Then came the prospectors looking for lost treasures—they’ve never gone away.”

FACT-CHECK

Why do the Rough Riders have such strong ties to Las Vegas, New Mexico?

“Most of the Rough Riders were New Mexican. One year after they captured San Juan Hill, they held their first reunion in Las Vegas. Ten thousand people came, with the train depot right there,” says Mark Lee Gardner, author of Rough Riders: Theodore Roosevelt, His Cowboy Regiment, and the Immortal Charge Up San Juan Hill. “Eventually, the Rough Rider Association donated their papers to Las Vegas for the Rough Rider Memorial.” —Jennifer Levin

Different versions of the padre tale surface across the Southwest, often braided with other legends and locations. (The Victorio Peak treasure near White Sands even merited its own Unsolved Mysteries episode.) But hard evidence for La Rue’s mine is scarce. Franciscan scholar Fray Angélico Chávez reportedly found no trace of La Rue’s existence, and geologists have long doubted the Organ Mountains ever held a mother lode. According to historian George Adlai Feather, the story stems from a jumbled account of a Lincoln County merchant named LaRue, who did exploratory work in the San Andres Mountains in 1879.

Rumors flew from then on. In the 1880s, Texas and New Mexico newspapers traded stories of the “lost padre” mine. In 1886, the Las Cruces Sun-News described a local couple who returned from a weekend excursion “very pleased with their prospecting trip,” having stumbled upon an old smelter. “Is this the long lost Padre mine?” the paper mused.

In the early 1930s, more elaborate tales in George Griggs’s History of Mesilla Valley and folklorist J. Frank Dobie’s Coronado’s Children spurred a fresh gold rush in the Organ and San Andres ranges. “It was the Depression,” Bullis says, “so the notion of finding treasure to get people out of the hard times was popular.”

In Santa Fe, the story even inspired the name of Lost Padre Records, a vinyl shop George Casey opened seven years ago. “I’m not about to grab a mule and a shovel,” Casey says, “but I think it’s fascinating what these stories tell us about people.” For him, the mine endures as a parable of desire—of kindness repaid, lives risked, fortunes sought, and the lengths humans go to for discovery.

“It’s the most American thing ever,” he adds. “We’re still pulling metals, oil, gas, lithium out of the ground in that part of the state. The digging never stopped.”

Treasure seekers like Felipe La Rue weren't alone in their pursuit of gold. Melvin Mills of Springer, New Mexico, built his fortune on similar dreams.

SEE FOR YOURSELF

Find hiking gold along the three-mile out-and-back Dripping Springs Trail in Organ Mountains–Desert Peaks National Monument. This moderate trek passes remnants of the Dripping Springs Resort, which operated in the late 19th century, as well as a monsoon-season waterfall, and dramatic rock formations. Stop at the Dripping Springs Visitor Center to learn more about the area’s history and geology.