As a part of New Mexico Magazine's centennial celebration, we'll be looking back at some of the stories from the past 100 years. This story appeared in the August 1960 edition.

IF WILL SHUSTER ever sat through the original Frankenstein and the Monster movie, he’d probably suspect that Hollywood had stolen his autobiography.

Way back in 1926, Shuster created his own monster. He was promptly captured by it. This summer, 34 years later, the white-haired Santa Fe artist is making his third attempt to escape. But fellow Santa Feans won’t believe it until they see what happens on the wild Friday night before Labor Day, which opens the fun side of their Ancient City’s ancient fiesta.

Shuster’s monster is Zozobra, the Gloomy One, or better known in Santa Fe as “Old Man Gloom,” the world’s largest animated puppet, which he has been building all these 34 years. His disfigured nose is half the size of a full-grown man, his head measures nine feet from cleft chin to widow’s peak, he is 40 feet tall from toes to topknot, and he tips the scale in the vicinity of 1,500 pounds.

Every summer for most of Shuster’s adult life, this monster has required a month or more of hard labor on the part of his creator. “Multiply a month by the 33 years I’ve been stuck with him and you get 33 months,” says Shuster. “That’s almost three years out of my life, and it doesn’t include the time spent on the preliminaries—and if I can’t pass him off on somebody else this year, it will be 34 months shot.” In the last five or six years the Santa Fe Kiwanis Club has been very active in building and putting on the show of Zozobra. Shuster says that some of the main problems have been taken over by the Kiwanis, but to assure that he be on hand for the event—and the work that goes into making the monster—they made him an honorary Kiwanian.

Whether or not Shuster finds satisfactory foster parents for his beast, Santa Fe has no doubt that Zozobra will be back again this fall.

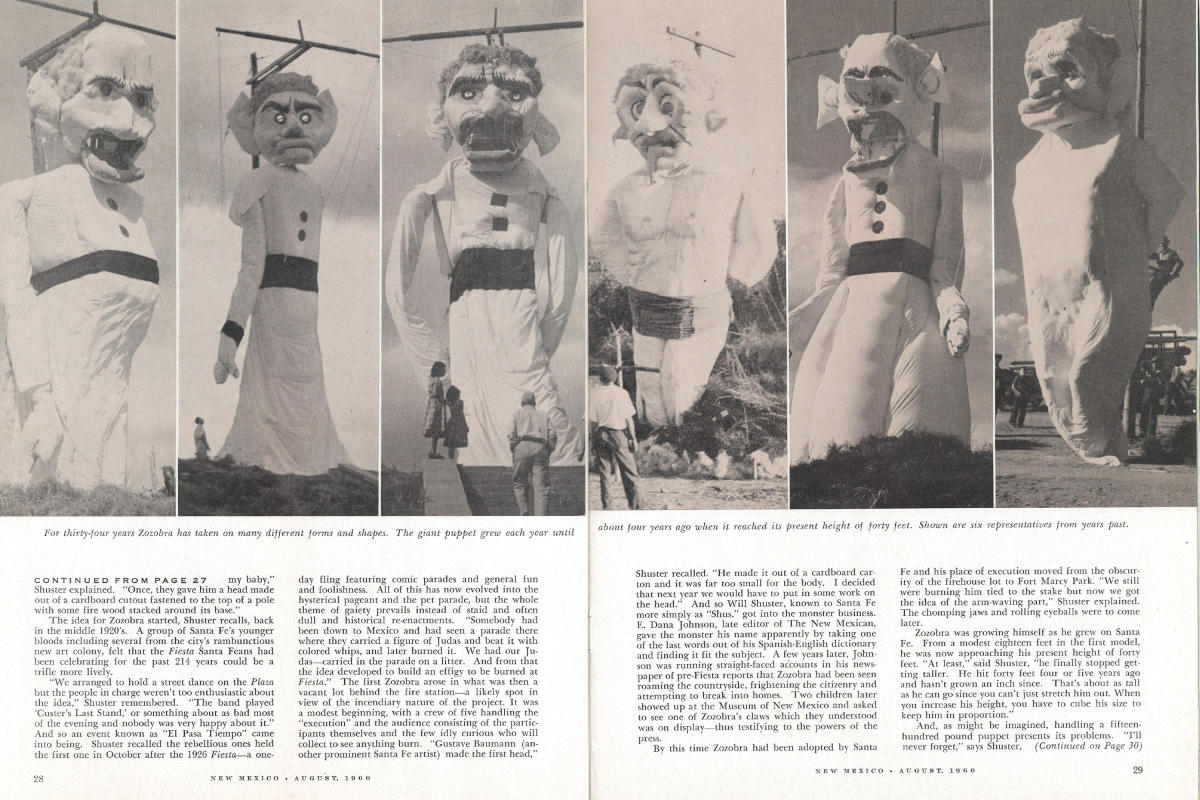

During its history, Zozobra has taken many forms and shapes. Here are six representations from Old Man Gloom's first 34 years.

During its history, Zozobra has taken many forms and shapes. Here are six representations from Old Man Gloom's first 34 years.

On the Friday afternoon before the Labor Day weekend he will rise again on the hillside overlooking Fort Marcy Park, using a Public Service Company of New Mexico power line pole for a backbone. That night, the gigantic puppet will be both guest of honor and victim at one of the largest and loudest celebrations in the West. With his ponderous arms waving, thunderous loudspeaker groans issuing from his wagging jaws, and pumpkin-sized eyeballs rolling evilly, Zozobra will go up once again in a towering column of flames. Overhead salvos of aerial bombs will be exploding, massed batteries of roman candles will be shooting their stars, horns of thousands of parked autos will be adding to the din, and mariachi bands up from Mexico to join in fiesta will be competing in vain with the uproar. A visitor from the Lone Star State once remarked, after witnessing the bedlam, that he hadn’t “seen or heard anything like it since the Texas City disaster [a 1947 industrial accident].”

Behind the smoke, fireworks, and flame, a small army of volunteers will be toiling at the task of properly executing Old Man Gloom. Zozobra’s puppet strings are sturdy ropes. It takes a squad of men dashing back and forth at the end of them to produce an awe-inspiring wave of the giant’s arm, to drop his jaw or roll an eyeball. Other crews man the battery of fireworks mortars, the loudspeaker, and carry on the costumed ritual which has become a traditional part of the burning. Directing this well-organized melee stands Shuster, engrossed with the job of seeing that the monster he has spent a month to build is promptly reduced to ashes for the edification of the crowd.

From backstage, the scene reminds one of a frantic band of Lilliputians besetting a highly inflammable Gulliver.

Strange as it seems, Shuster has to rely on reports from the audience on the appearance from a distance of the spectacle he created. He has always been ram-rodding the production from his position “front stage.” “But this year,” he says, “I hope I can sit out in Fort Marcy and see for myself how he looks from a distance. After all these years, it’s about time I got to watch the show from that vantage point.”

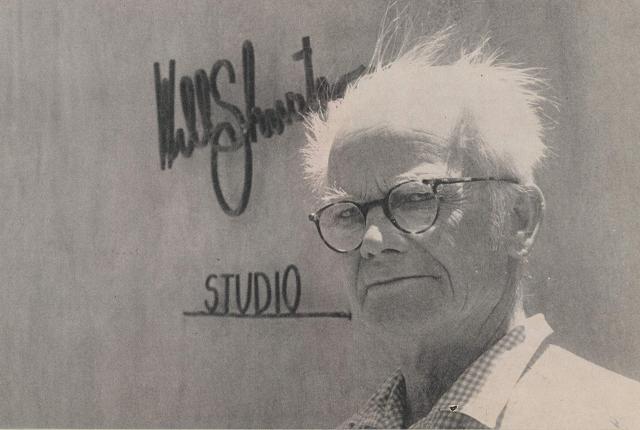

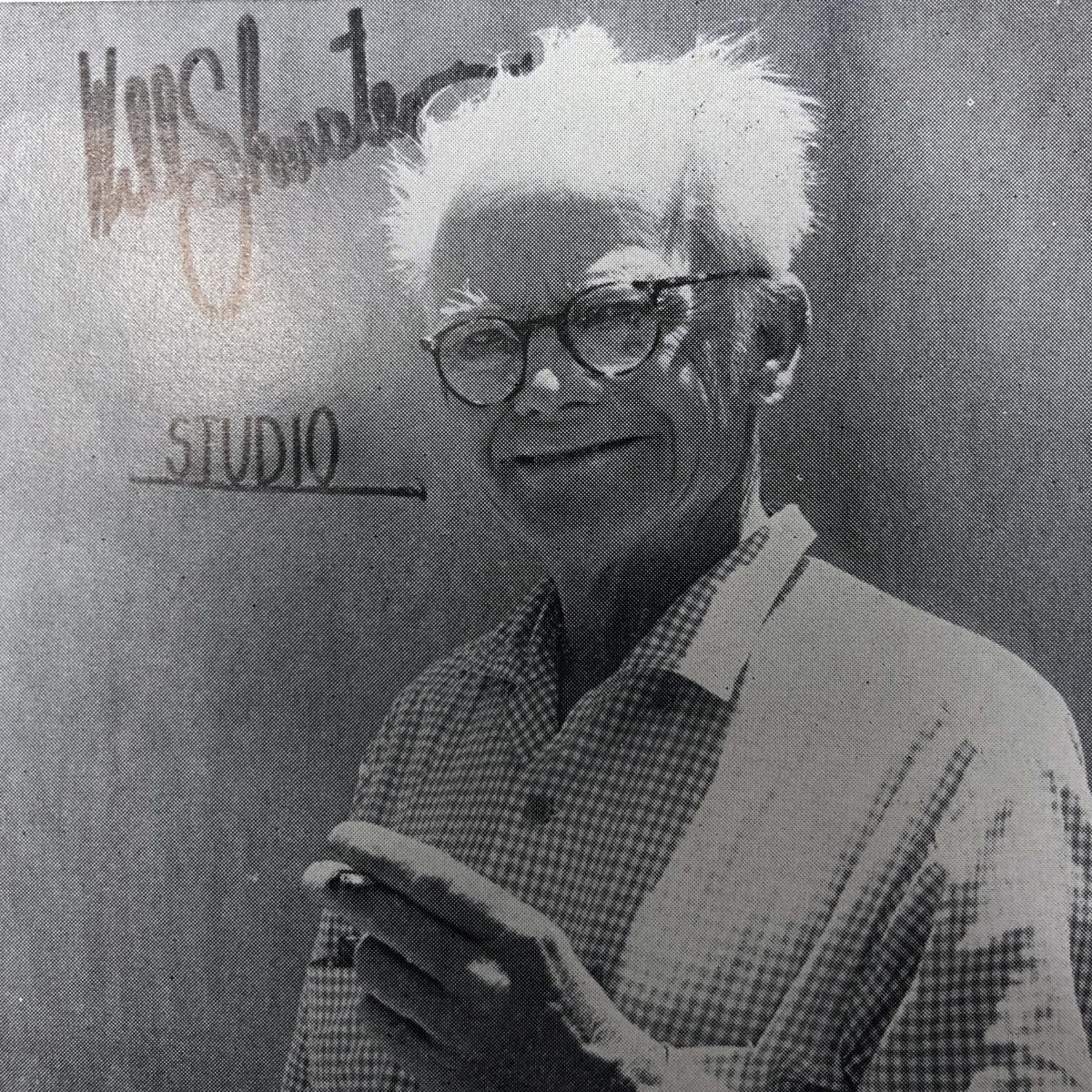

Will Shuster has captured the hearts of Santa Feans with his willingness to lend a helping hand and his seemingly endless vitality. Photograph by Mike James.

Will Shuster has captured the hearts of Santa Feans with his willingness to lend a helping hand and his seemingly endless vitality. Photograph by Mike James.

Shuster’s friends—and that includes a remarkably large percentage of Santa Fe’s 34,000 citizens—will tell you that he was trapped into the grueling annual task of monster building strictly through his own fault. Shuster’s Zozobras came in many models—especially in earlier years—but whether they were bald with sagging jowls or featured ferocious jutting features under black fright wigs, they were always just the thing to capture Santa Fe’s lively imagination. Almost before Shuster and the Fiesta Council knew what was happening, Zozobra had become a Santa Fe tradition. The “City Different” suddenly found that it could no more have Fiesta de Santa Fe without Zozobra than Boston could celebrate Patriot’s Day without fife and drum. Nor, it seemed, could there be Zozobra without Shuster. Twice in years gone by, the white-thatched artist attempted to abandon his unsightly creature. But it didn’t work out. “Each time I felt discouraged about the way they treated my baby,” Shuster explained. “Once, they gave him a head made out of a cardboard cutout fastened to the top of a pole with some firewood stacked around its base.”

The idea for Zozobra started, Shuster recalls, back in the middle of the 1920s. A group of Santa Fe’s younger bloods, including several from the city’s rambunctious new art colony, felt that the fiesta that Santa Feans had been celebrating for the past 214 years could be a trifle more lively.

“We arranged to hold a street dance on the Plaza but the people in charge weren’t too enthusiastic about the idea,” Shuster explained. “The band played ‘Custer’s Last Stand,’ or something about as bad most of the evening, and nobody was very happy about it.” And so an event known as “El Pasa Tiempo” came into being. Shuster recalled the rebellious ones held the first one in October after the 1926 Fiesta—a one-day fling featuring comic parades and general fun and foolishness. All of this has now evolved into the hysterical pageant and the pet parade, but the whole theme of gaiety prevails instead of staid and often dull historical re-enactments. “Somebody had been down in Mexico and had seen a parade there where they carried a figure of Judas and beat it with colored whips, and later burned it. We had our Judas—carried in the parade on a litter. And from that the idea developed to build an effigy to be burned at the fiesta.”

The first Zozobra arose in what was then a vacant lot behind the fire station—a likely spot in view of the incendiary nature of the project. It was a modest beginning, with a crew of five handling the “execution” and the audience consisting of the participants themselves and the few idly curious who will collect to see anything burn. “Gustave Baumann [another prominent Santa Fe artist] made the first head,” Shuster recalled. “He made it out of a cardboard carton and it was far too small for the body. I decided that next year we would have to put in some work on the head.” And so, Will Shuster, known to Santa Fe more simply as “Shus,” got into the monster business. E. Dana Johnson, late editor of The New Mexican, gave the monster his name apparently by taking one of the last words out of his Spanish-English dictionary and finding it fit the subject. A few years later, Johnson was running straight-faced accounts in the newspaper of pre-fiesta reports that Zozobra had been seen roaming the countryside, frightening the citizenry and attempting to break into homes. Two children later showed up at the Museum of New Mexico and asked to see one of Zozobra’s claws, which they understood were on display—thus testifying to the powers of the press.

By this time, Zozobra had been adopted by Santa Fe and his place of execution moved from the obscurity of the firehouse lot to Fort Marcy Park. “We still were burning him tied to the stake but now we got the idea of the arm-waving part,” Shuster explained. The chomping jaws and eye rolls were to come later.

On the Cover

On the Cover

Visitors at the Fort Wingate and Gallup Ceremonials will find a fascinating formation of brilliantly colored sandstone known as Red Rocks. Photographer George C. Hight finds tourists on horseback exploring the unusual attractions.

Zozobra was growing himself as he grew on Santa Fe. From a modest 18 feet in the first model, he was now approaching his present height of 40 feet. “At least,” said Shuster, “he finally stopped getting taller. He hit 40 feet four or five years ago and hasn’t grown an inch since. That’s about as tall as he can go since you can’t just stretch him out. When you increase the height, you have to cube his size to keep him in proportion.”

And, as might be imagined, handling a 1,500-pound puppet presents its problems. “I’ll never forget,” says Shuster, “the year we dropped him.”

“We always put a snatch block at the bottom of the pole and a block and tackle at the top but this year they left off the snatch block. The pole broke and dumped all forty feet of him right on the ground, and of course it was Friday afternoon, just a few hours before showtime.”

Zozobra underwent major surgery for a broken arm and various abrasions, a new pole was quickly erected, and the show went on as scheduled.

In all the years since 1926, the show has always gone on, although there was a time or two when it almost didn’t.

“Once, and I’ll never forget it, when the time came to touch him off nobody had a match. We had to send out into the crowd to get something to light him with,” Shuster said. “But as usual, it went off alright.”

“And then there was a time when we had a governmental dignitary up from Mexico to preside over the ceremonies. He was supposed to make a speech and then ceremoniously light the powder train to start the burning of Zozobra. But one of the ‘Glooms,’ the attendants for the execution, got a little careless with his torch and set the thing off prematurely,” Shuster said. “I always suspected that it was no accident,” he added. “A lot of the Glooms had been belting the bottle a little.” Even that year, the show went off satisfactorily, although the Mexican official was cheated of his moment of glory.

Read More: The Complete 50 Reasons to Love Santa Fe.

Jaques Cartier, Santa Fe ballet instructor and well-known performer, plays an important role in the execution of Zozobra. Each year he performs a dance and supervises the little Glooms in a “ritualistic” performance preceding the burning.

And then there was the year when the dancers didn’t show up. The preliminary dancing—a ritual involving a platoon of heavily costumed Glooms paying homage to Zozobra was to have been handled that year by a troop performing in a fiesta pageant.

“But they backed out due to the fire hazard,” Shuster recalled, without apparent bitterness. “Luckily the Pueblo Indians were in town for a dancing competition of their own. I went over to their encampment with an interpreter and found the governor of Picuris Pueblo and told him we had decided to give him the honor of lighting the fire. The show [they] put on was the most wonderful thing you ever saw—and it was strictly right off the cuff without any plans or rehearsing.”

Actor Errol Flynn, in town for a premiere of Santa Fe Trail, lights the bonfire to "Zozobra." Photograph courtesy of Warner Brothers Studio.

Actor Errol Flynn, in town for a premiere of Santa Fe Trail, lights the bonfire to "Zozobra." Photograph courtesy of Warner Brothers Studio.

Shuster thumbed through a stack of mementoes from Zozobra’s past on his studio desk. “Here’s a photograph I always liked,” he said, displaying a glossy print. The photograph was a closeup of the late Errol Flynn, swashbuckling hero of the motion pictures, about to light a fire that would consume one of the giant puppets made by Shuster. “It was not an actual ‘Zozobra,’” Shuster explained. “They were having the premiere of The Santa Fe Trail here, and many of the stars were here for the event, including Flynn. So we built a sort of ‘second-cousin’ to Zozobra to celebrate the event.”

The photograph shows Flynn holding the match at an extreme arm’s length—his face contorted with terror and distaste. “Probably he was afraid of getting scorched,” Shuster explained.

Shuster then returned to his favorite subject—his recurrent dream of foisting off on someone else the job of building Santa Fe’s traditional monster and producing the spectacle of his burning.

“I think I’m going to get away with it this year. Alex Jordan has been heading the Kiwanis Club committee which helps in the production and is a real good Zozobra hand. So is George Roy. They can do it.” Roy has served with Shuster for several years as the co-director of the production.

After 33 years, all of Santa Fe knows there has to be a Zozobra. If you don’t burn Old Man Gloom, the aspens might not turn their autumn yellow on the mountains and winter would surely bring gloom and doom. And Santa Feans will bet that when Zozobra begins taking his massive shape in the National Guard Armory garage, “Shus” will be there at least as a very interested spectator.

And when Zozobra meets his fearsome demise, filling another crop of Santa Fe children with delicious terror and their parents with an unexplainable glee, the odds are good that Shuster will be backstage again, missing another show.

Santa Fe … and fiesta … will continue in the future as in the past, and there will be Zozobras—but Will Shuster will always be part of the celebration.

Big as it is, it’s his baby.

The late Tony Hillerman is the much-lauded author of a mystery series featuring Diné law-enforcement officers Joe Leaphorn and Jim Chee.

Attend the 98th Burning of Will Shuster’s Zozobra on September 2 at Fort Marcy Park, in Santa Fe. The event begins with entertainment at 4 p.m.

Actor John Thomas pauses in front of the Wortley Hotel to finger his six-shooter, much as Billy the Kid might have done. Photograph by Martin Elkort.

Actor John Thomas pauses in front of the Wortley Hotel to finger his six-shooter, much as Billy the Kid might have done. Photograph by Martin Elkort.

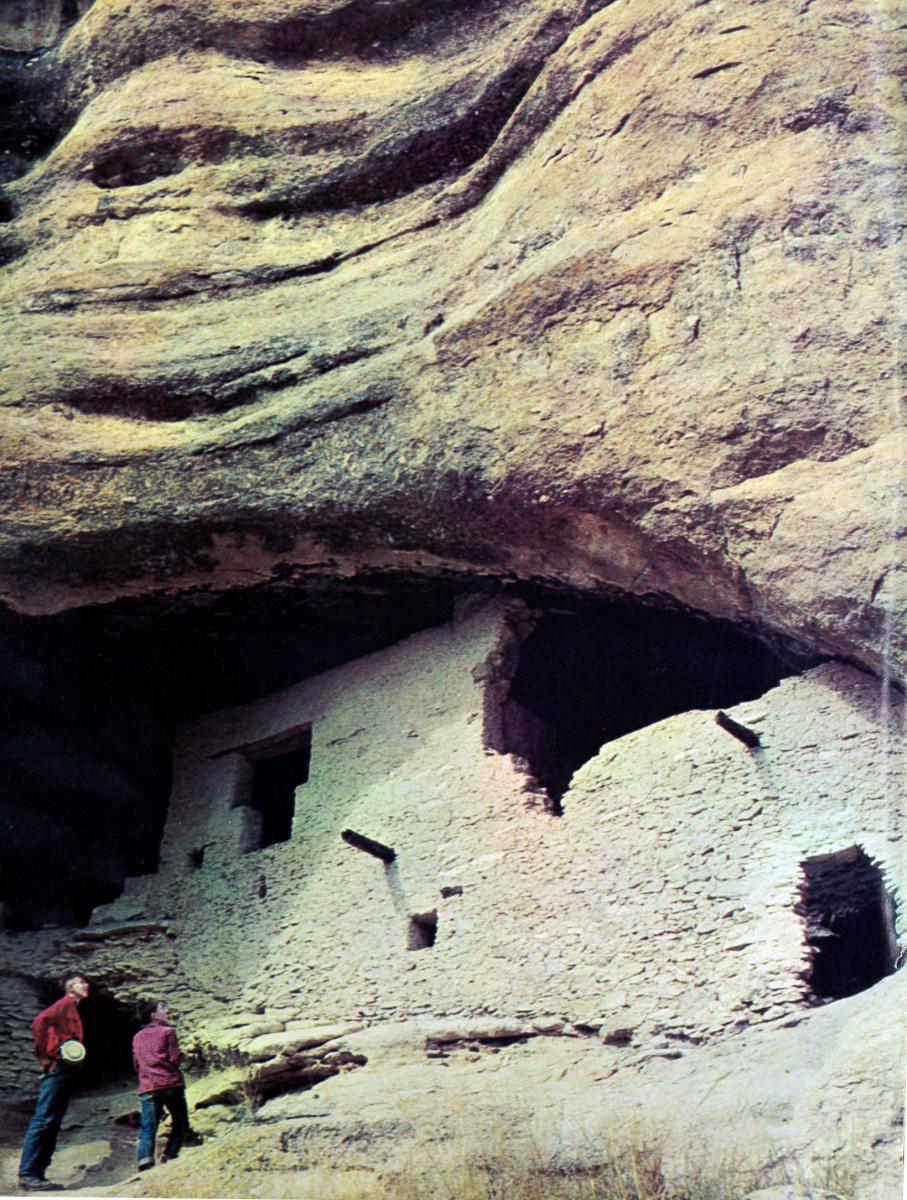

Ancestral people made their homes in these natural caves on a mountainside in Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument. Photograph by R.P. Meleski.

Ancestral people made their homes in these natural caves on a mountainside in Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument. Photograph by R.P. Meleski.

Trip of the Month

“In your search for the Gila Cliff Dwellings, you penetrate a wilderness of piled up mountain ranges blanketed with black forests. A wild, wonder-filled world slashed through with deep canyons and narrow, shadowed gorges. A place so remote that only jeeps and horses can get you there.” —from “To the Gila Cliff Dwellings,” by Betty Woods