THE SLOPE-SHOULDERED OUTLINES AND EARTHEN HUES of adobe buildings root themselves in New Mexico. Bricks made from sun-dried clay, sand, straw, and water lend themselves to everything from a sturdy stable to a sculpted mansion. One of the earliest forms of eco-construction, adobe masonry techniques migrated from northern Africa and southern Spain with 17th-century Spanish colonists. Here, the practice merged with the earlier mud-building skills of indigenous peoples and soon became all the rage.

At its best, adobe construction requires community. People gather to craft the bricks, stack them into structures, and return year after year to maintain simple mud-plaster facades. The handprints of centuries’ worth of people remain forever a part of these structures, testaments to artistry and heart.

Although they are clustered in the Río Grande Valley, adobe buildings populate the state. We picked 38 of our favorites, where you can eat, stay, uncover the past, or just appreciate the workmanship.

Jump To: Churches, Restaurants, Historic Sites, Museums, Lodging, Ghost Towns, Public Buildings

Plus: Why Adobe?, and Get Muddy

The flowing lines of San Francisco de Asís Mission, in Los Ranchos de Taos, attract artists and photographers. Sumiko Scott/Getty Images.

CHURCHES

San Francisco de Asís Mission, Los Ranchos de Taos

The most photographed church in the state, San Francisco de Asís features wide adobe buttresses that support the two-story structure and give it a sculptural quality. Its ability to capture light and cast shadows has drawn artists like Georgia O’Keeffe and Ansel Adams, and many plein air painters. “The adobe itself looks so beautiful in every type of daylight and moonlight,” says curator and parish archivist Guadalupe Tafoya. “It’s a graceful church.”

The church anchors the 18th-century, U-shaped San Francisco Plaza, which was once a presidio (home to a Spanish military garrison). Five-foot-thick walls support two working bell towers. Inside, the mission displays several original bultos and retablos from notable 19th-century artists, including José Rafael Aragón, whose work is considered a pinnacle of the era’s santeros.

Father José Benito Pereyro celebrated the church’s first Mass in July 1815, and parishioners have continually maintained the structure with enjarres (communal plasterings) every June since the founding. “It’s the heart of the community,” Tafoya says. “It’s a physical representation of our spirituality, and it binds us as a community.”

This you gotta see: By appointment only, visitors can witness the church’s “miraculous” artwork, Henri Ault’s 1896 painting The Shadow of the Cross. As you sit in the dark parish hall, a previously invisible cross luminesces in the painting.

San Francisco de Asís, 60 St. Francis Plaza, Los Ranchos de Taos, 575-758-2754.

El Santuario de Chimayó

Considered the most important Catholic pilgrimage site in the country, this humble mission receives some 300,000 sightseers a year. Most visitors head to el pocito (the little well), a source of healing dirt for the faithful.

El Santuario de Chimayó, 15 Santuario Dr., 505-351-9961.

The sanctuary of San Miguel de Socorro Mission. Photograph by Glenn Nagel/Alamy.

The sanctuary of San Miguel de Socorro Mission. Photograph by Glenn Nagel/Alamy.

San Miguel de Socorro Mission, Socorro

In 2015, this parish marked its 400-year anniversary with a massive restoration of its mother church. Originally built in 1626, the adobe mission was rededicated in 1821 to Saint Michael the Archangel, as its large stained-glass window attests.

San Miguel de Socorro, 403 El Camino Real, 575-835-2891.

The San Esteban del Rey Mission dates to 1629. Photograph by Stephen Power/Alamy.

San Esteban del Rey Mission, Acoma Pueblo

Perched on the edge of Acoma Pueblo’s Sky City and on view during guided tours and feast days, this fine example of blended Spanish and Puebloan architecture dates to 1629. Its mud came from the valley floor, 360 feet below. The timber for its wooden vigas was carried on foot from the San Mateo Mountains, 30 miles away.

San Esteban del Rey, Acoma Pueblo, 800-747-0181.

San José de Gracia Church, Las Trampas

Set on the High Road to Taos, the village of Las Trampas was founded in 1751, and its church stands as a national historic landmark. Admire the works of 18th- and 19th-century santeros inside, and look up to see painted designs on a part of the ceiling.

2377-2381 NM 76, 505-351-4360

Cristo Rey Church, Santa Fe

John Gaw Meem, the celebrated Southwest architect, designed this Depression-era adobe church to accommodate a 1760 stone reredos. It may be the largest adobe building in the nation. Workers, many of them parishioners, poured up to 4,800 adobe bricks a day.

Cristo Rey, 1120 Canyon Road, 505-983-8528.

The Double Eagle Restaurant, in Mesilla, began as a single building but now covers some 14,000 square feet. Courtesy of Double Eagle Restaurant.

The Double Eagle Restaurant, in Mesilla, began as a single building but now covers some 14,000 square feet. Courtesy of Double Eagle Restaurant.

RESTAURANTS

Double Eagle Restaurant, Mesilla

One of Mesilla’s most celebrated restaurants began as a humble jacal (a wooden structure with earth mounded on the walls). In the 1850s, the residential owners sandwiched the jacal with adobe bricks, says Double Eagle’s owner, C.W. “Buddy” Ritter. What began as a single room now sprawls over an entire block, covering some 14,000 square feet. The structure houses two restaurants: the fine-dining Double Eagle, where aged steaks and margaritas top the menu, and the laid-back Peppers on the Plaza.

In 1984, Ritter purchased the rambling adobe, which housed one of Robert O. Anderson’s many restaurants throughout the state. The oil and land magnate had an affinity for restoring historic buildings, turning them into restaurants, and giving them money-themed names such as the Double Eagle (a nickname for a $20 gold piece), the Legal Tender, in Lamy, and the Tinnie Silver Dollar, in the Hondo Valley.

Ritter has preserved many original and period elements, including the original vigas and latillas in the Juarez-Díaz room, and an 1880s tin ceiling in the Imperial Bar and Lew Wallace Lounge. In the Maximilian Room, three Baccarat crystal chandeliers hang from gold-plated ceilings.

What goes around: “I’m a fifth-generation New Mexican,” Ritter says. “My grandmother’s grandfather was the first surgeon in this area who was in private practice. His offices were where the Double Eagle now is. My office is now where his once was.”

Double Eagle Restaurant, 2355 Calle de Guadalupe, 575-523-6700.

The Shed, Santa Fe

Known for classic New Mexican cuisine, the Shed serves some of the state’s best red in nine rooms of a 17th-century adobe hacienda. The sunny Prince Patio takes its name from territorial governor Bradford Prince, who occupied these rooms with his family beginning in 1879.

The Shed, 113½ E. Palace Ave., 505-982-9030.

Church Street Café, Albuquerque

Housed in Old Town’s Casa de Ruiz, one of the oldest buildings in the Duke City, this New Mexican restaurant is built of terrones—adobe bricks made of sod or cut from riverbanks and cured.

Church Street Café, 2111 Church St. NW, 505-247-8522.

La Fonda del Bosque, Albuquerque

Once a school and now home to a Latin fusion restaurant on the campus of the National Hispanic Cultural Center, this WPA-era Pueblo Revival adobe is an exception to the more common bricks-and-lumber construction of its time.

La Fonda del Bosque, 1701 4th St. SW, 505-800-7166.

The Compound Restaurant, in Santa Fe, got a midcentury-modern redesign in the 1960s. Photograph by Gabriella Marks.

The Compound Restaurant, in Santa Fe, got a midcentury-modern redesign in the 1960s. Photograph by Gabriella Marks.

The Compound Restaurant, Santa Fe

Prior to life as an elegant restaurant, this adobe housed artists and their studios. It deepened its art bona fides when renowned textile designer (and Santa Fean) Alexander Girard redesigned the restaurant with built-to-last midcentury-modern flair in the 1960s.

The Compound Restaurant, 653 Canyon Road A, 505-982-4353.

Buckhorn Saloon and Opera House, Pinos Altos

Seven mountainous miles north of Silver City, this saloon boasts a #gramworthy facade straight out of a period Western. Dating back to the Civil War era, it has 18-inch-thick adobe walls and traditional vigas—and still serves strong drinks and steaks worth the drive.

Buckhorn Saloon and Opera House, 32 Main St., 575-538-9911.

HISTORIC SITES

Gutiérrez-Hubbell House, Albuquerque

From its construction in the 1860s until 1996, the Gutiérrez-Hubbell House was a family home, but often far more than a residence. Built for newlyweds Julianita Gutiérrez, who hailed from a wealthy Mexican family, and Connecticut-born James Lawrence “Santiago” Hubbell, the structure enjoyed a prime spot along El Camino Real and served as a trading post, stagecoach stop, post office, and mercantile. “It’s not a typical house of the time,” says Francisco Uvina, director of a historic preservation program at UNM, who helped the building’s transformation into a museum, demonstration farm, and event center. “This was a well-to-do family.”

A six-year rehab by Cornerstones Community Partnerships, a Santa Fe–based adobe-preservation nonprofit, and Bernalillo County earned a National Trust for Historic Preservation Award in 2009. It preserved the blend of Spanish Colonial, Mexican, and American building styles—including symmetrical rooms, sawed lumber in the roof deck, and glazed windows—typical of the Territorial style.

“There was a huge coming of new materials, and governments, and languages at this time,” Uvina says. “The Hubbells were really evolved.”

Any relation to … ? One of the entrepreneurial couple’s 12 children, Juan “Lorenzo” Hubbell, established the Hubbell Trading Post, in Ganado, Arizona, now a national historic site.

Gutiérrez-Hubbell House, 6029 Isleta Blvd. SW, 505-244-0507.

Fort Union National Monument, Watrous

The remnants of Territorial-style adobe soldiers’ quarters and other military structures still stand outside Las Vegas—the largest fort in the region in the 19th century. Living history encampments and dazzling star parties add to the allure.

Fort Union National Monument, 3115 NM 161, 505-425-8025.

Old Lincoln County Courthouse, Lincoln

This two-story Territorial adobe anchors the Lincoln Historic Site, which includes 17 structures from the 1870s and ’80s. Now a museum recounting the Lincoln County War, it still bears the (purported) bullet holes left from Billy the Kid’s daring escape.

Old Lincoln County Courthouse, On US 380, about 12 miles southeast of Capitán, 575-653-4025.

Taylor-Mesilla Historic Property, Mesilla

Made up of three connected buildings—two storefronts on the Mesilla Plaza and a large residence—this authentic site is filled with family heirlooms and tales of life amid southern New Mexico’s borderlands.

Taylor-Mesilla Historic Property, open by appointment, 575-202-1638.

Tour the Los Luceros Historic Site, which also features an apple orchard. Photograph by Inga Hendrickson.

Tour the Los Luceros Historic Site, which also features an apple orchard. Photograph by Inga Hendrickson.

Los Luceros Historic Site, Alcalde

The Territorial home, which earned a place on the National Register of Historic Places, looks out upon a property that spans the colonial era through the 20th century and sheltered luminaries like Mary Cabot Wheelwright. (Come on a fall weekend for heirloom apple picking.)

Los Luceros Historic Site, 253 CR 41, Alcalde, 505-476-1165.

Cleveland Roller Mill Museum, Cleveland

The towering 18-foot-tall cast-iron wheel that milled flour here in the late 1800s turns during Millfest, on Labor Day weekend, when visitors can also wander the enormous adobe millhouse.

Cleveland Roller Mill Museum, on NM 518 near Mora, 575-387-2645.

MUSEUMS

Palace of the Governors, Santa Fe

The oldest continually used government building in the nation, the Palace, part of the New Mexico History Museum, was built on the Santa Fe Plaza as a Spanish seat of government. “It’s an iconic symbol—whether good or bad—of New Mexico’s history and the container of over 400 years of the life of New Mexico’s people as we understand it through its governments, institutions, and traditions,” says archaeologist Steve Post, who is co-curating a coming exhibition there.

With the building closed for renovations, Post has explored the secrets held within it. The Palace that visitors see today, he says, “is not what people were living in and walking through in the 1650s or even the 1950s. The changes were both subtle and drastic.” For example, remains of three-foot-thick foundation walls suggest that the Palace once stood two stories tall. Vigas hail from many sources and time periods. Historians use these elements to track its evolution from Spanish to Mexican and American territorial offices to, finally, a museum. “The specifications aren’t talked about in the historical documents,” he says. “Without the building itself, that information would be lost to time.”

What a dinner guest: In 1807, explorer Zebulon Pike, arrested for illegally entering the Spanish colony, enjoyed one dinner in the Palace before being hauled to Mexico City to face the Inquisition.

Palace of the Governors, 105 W. Palace Ave., 505-476-5200.

El Rancho de las Golondrinas, Santa Fe

Once a paraje (stopover) on El Camino Real, this historic “ranch of the swallows,” with original adobes dating to the 17th century, is a family-friendly living history museum preserving Spanish colonial lifeways—including bread baked in adobe hornos.

El Rancho de las Golondrinas, 334 Los Pinos Road, 505-471-2261.

An example of a preserved Spanish colonial style home can be found at the Kit Carson Home and Museum, in Taos. Photograph by John McCauley.

An example of a preserved Spanish colonial style home can be found at the Kit Carson Home and Museum, in Taos. Photograph by John McCauley.

Kit Carson Home and Museum, Taos

The frontiersman purchased this home for his third wife, Maria Josefa Jaramillo, in 1843, and they resided here for 27 years. The Grand Masonic Lodge of New Mexico now owns and maintains it as a museum and memorial to its fellow freemason.

Kit Carson Home and Museum, 113 Kit Carson Road, 575-758-4082.

Get a glimpse into Georgia O'Keeffe's life at the Georgia O’Keeffe Home and Studio. Photograph by Krysta Jabczenski, 2019, © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum.

Get a glimpse into Georgia O'Keeffe's life at the Georgia O’Keeffe Home and Studio. Photograph by Krysta Jabczenski, 2019, © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum.

Georgia O’Keeffe Home and Studio, Abiquiú

When the modernist painter bought this home, it was a mess—but it soon became her muse. After extensive preservation and renovation, it inspired her paintings of its adobe walls and the cottonwoods in the Chama River Valley.

Georgia O'Keeffe Home and Studio, tours depart from the O’Keeffe Welcome Center, 21120 US 84, 505-685-4016.

Kit Carson Museum at Rayado, Philmont Scout Ranch

In the 1850s, this museum’s namesake, along with his U.S. Army Dragoons, provided security in Rayado, near Cimarrón, for land baron Lucien Maxwell. A century later, the Boy Scouts of America built an adobe museum here recounting Maxwell’s and Carson’s exploits.

Kit Carson Museum at Rayado, on NM 21, seven miles south of Philmont Scout Ranch’s camping headquarters, 575-376-1136.

Oldest House, Santa Fe

This dwelling’s vigas date its construction to 1740–67, but it didn’t earn its moniker until an 1882 map dubbed it the nation’s oldest house. (Historians differ on whether it’s truly the oldest.) It’s now a small museum and gift shop.

Oldest House, 215 E. De Vargas St., 505-988-2488.

The St. James Hotel in Cimarrón was built in 1872. Photograph by Jan Butchofsky/Alamy.

The St. James Hotel in Cimarrón was built in 1872. Photograph by Jan Butchofsky/Alamy.

LODGING

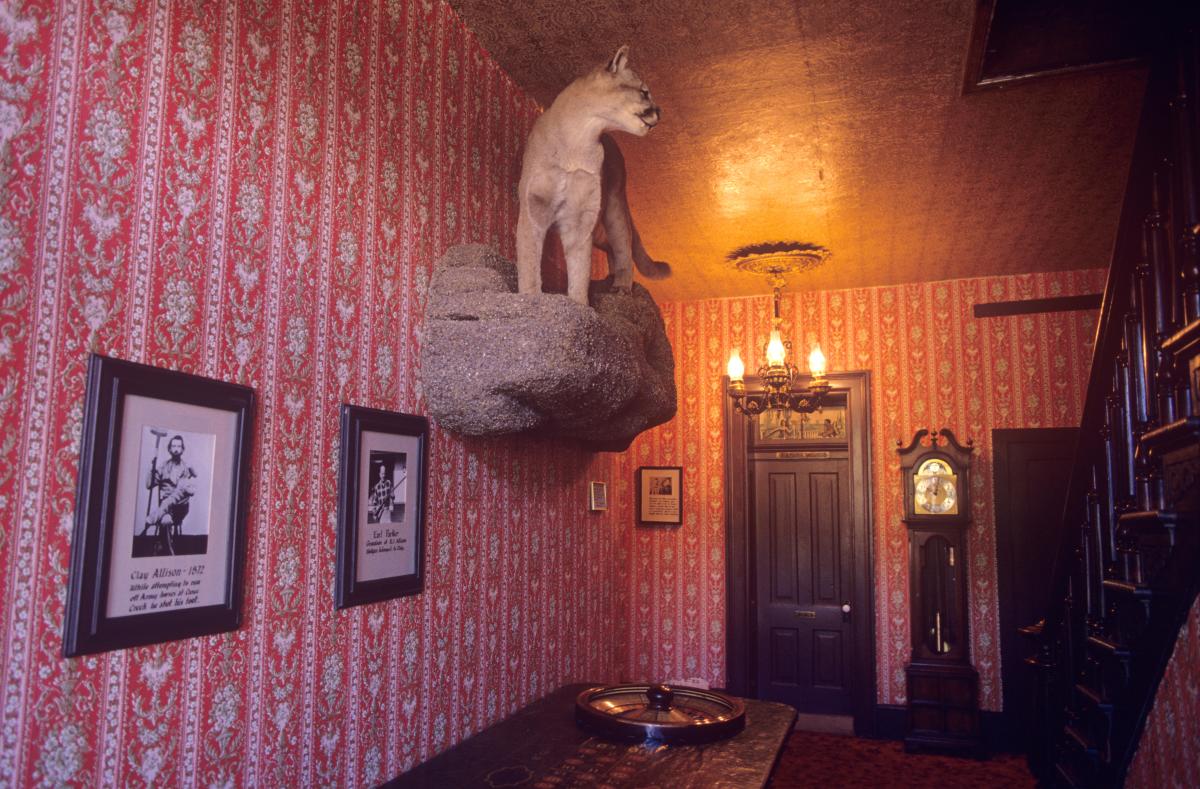

St. James Hotel, Cimarrón

With a name meaning “wild,” Cimarrón lived up to its reputation in the late 1800s, partly thanks to the drinking, gambling, and gunslinging at Lambert’s Place. Chef Henri Lambert built the two-story adobe that now houses St. James Hotel in 1872. His restaurant and hotel soon earned a less than desirable distinction: Twenty-six people are said to have been murdered in the saloon; bullet holes pockmark the pressed-tin ceilings.

Despite its unruly past, the hotel is quite demure today. After growing up near the St. James, Ed Sitzberger purchased and began restoring it in 1985. “I used to play in the hotel as a kid. I understood how important it was to the town,” says Sitzberger, who also co-authored History of the St. James Hotel: Cimarrón, New Mexico. Entrepreneur Bob Funk and his Express UU Bar Ranch group took over in 2009. Renovations added creature comforts, though the hotel keeps to its roots with circa-1880s air conditioning (aka open windows).

Some guests never leave: The spirit of Lambert’s wife, Mary, “still maintains possession” of the room where she once lived, Sitzberger says. Guests say they experience paranormal activity—perhaps that of the rowdy cowboys who met their ends here.

St. James Hotel, 617 S. Collinson Ave., 575-376-2664.

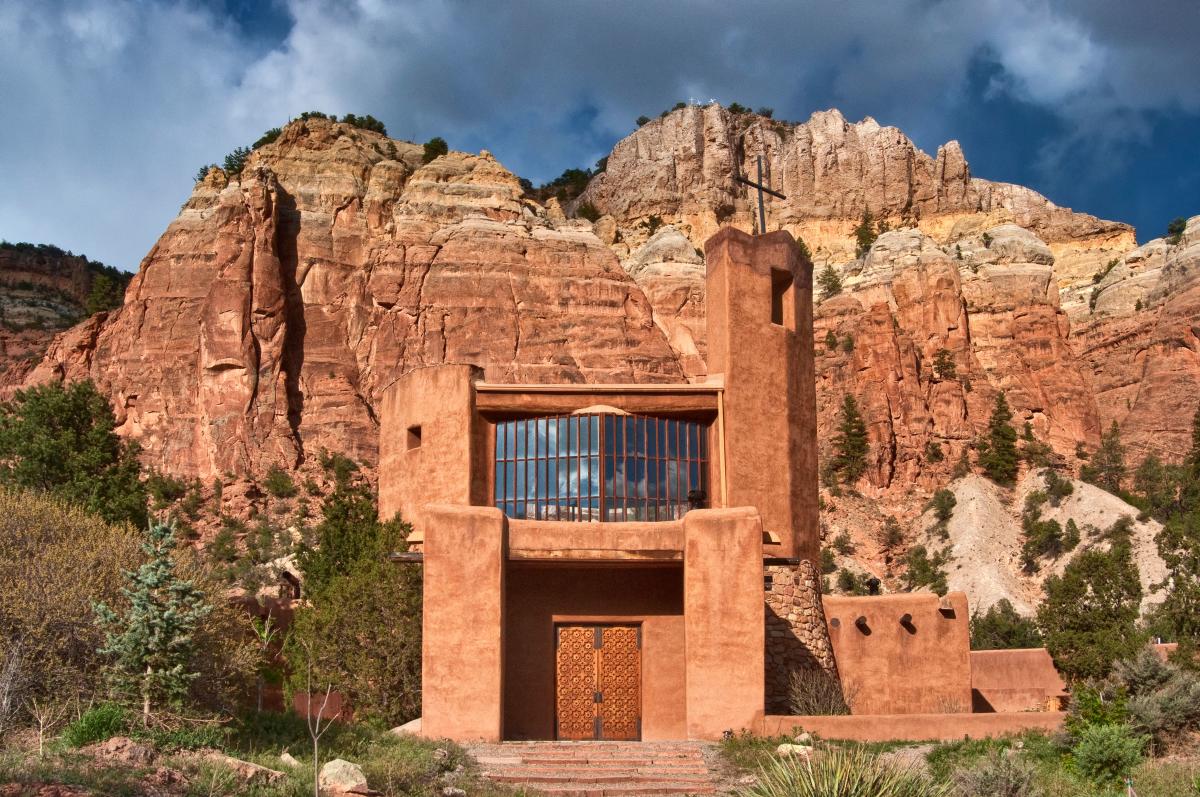

Monks still live and work at the Monastery of Christ in the Desert. Photograph by Witold Skrypczak/Alamy.

Monks still live and work at the Monastery of Christ in the Desert. Photograph by Witold Skrypczak/Alamy.

Monastery of Christ in the Desert, Abiquiú

Benedictine monks live, work, and welcome contemplative guests at this monastery near the Chama River Canyon Wilderness. Woodworker and designer George Nakashima planned the church, convento, and guesthouse.

Monastery of Christ in the Desert, see website for driving directions, 575-613-4233.

El Vado Motel, Albuquerque

An adobe lobby welcomes guests to this vintage Route 66 motel, fully renovated in 2018 with midcentury-modern guest rooms and a batch of hip restaurants and shops.

El Vado Motel, 2500 Central Ave. SW, 505-361-1667.

Casa del Gavilan Historic Inn, Cimarrón

Built as a family home in 1912, this charming villa at the base of Urraca Mesa, surrounded by Philmont Scout Ranch, is now a six-room bed-and-breakfast.

Casa del Gavilan Historic Inn, on NM 21, six miles southwest of Cimarrón, 575-376-2246.

Pueblo Bonito Bed & Breakfast Inn, Santa Fe

Doc Campbell, Billy the Kid, and Pancho Villa are said to have visited this downtown Santa Fe adobe in the 1800s. Since then, its 19 rooms have housed starving artists and Manhattan Project alumni.

Pueblo Bonito Bed & Breakfast, 138 W. Manhattan Ave., 800-461-4599.

Silver Creek Inn, Mogollon

This two-story, circa 1885 adobe structure anchors the ghost town of Mogollon, 74 miles north of Silver City. Kathy Knapp, aka the “Pie Lady of Pie Town,” is a part owner of the no-frills, four-room inn.

Silver Creek Inn, on NM 159.

Visit the adobe chapel at Lake Valley. Photograph by Jay Hemphill.

Visit the adobe chapel at Lake Valley. Photograph by Jay Hemphill.

GHOST TOWNS

Lake Valley Historic Site

A bustling mining settlement with as many as 4,000 residents, Lake Valley hit its boom nearly overnight after the Bridal Chamber mine revealed its treasure: silver that could be plucked from the walls by the ton. Most of the village burned to the ground in 1895. (A vengeful man is thought to have started the fire intentionally after his alcohol-induced escapades got him thrown out of the saloon.) However, a few buildings from the rebuild still stand on the townsite, which the Bureau of Land Management took over in 1992.

Until at least the 1970s, a variety of Protestant and Catholic denominations worshipped in its small adobe chapel when circuit-riding priests and pastors came through town. The original pews and dais still stand inside. “We’ve tried to maintain the buildings as they were throughout the site, so it’s like walking into the past,” says Kendrah M. Penn, branch chief for recreation and cultural programs at the BLM’s Las Cruces office.

Coming attraction: Cornerstones Community Partnerships plans to stabilize the Keil House, a onetime adobe residence whose interior still bears vestiges of its stylish wallpaper and decorative molding.

Lake Valley Historic Site, on NM 21, 17 miles south of Hillsboro, 575-525-4300.

Black Range Museum, Hillsboro

Built before 1893, this adobe houses a collection of town artifacts, including items from stagecoach driver and madam Sadie Orchard, and restaurateur Tom Ying, whose Victorian house still stands next door.

Black Range Museum, on NM 152, 575-895-3321.

San Francisco de Asís Church was restored in 1960. Stephen Saks Photography/Alamy.

San Francisco de Asís Church was restored in 1960. Stephen Saks Photography/Alamy.

San Francisco de Asís Church, Golden

In 1825, today’s “Turquoise Trail” birthed the first gold rush in the West, with the village of Golden at its heart. The boom went bust, but photographers adore its still-in-use church, which was restored in 1960 by noted author and artist Fray Angélico Chávez.

San Francisco de Asís Church, on NM 14, 11 miles south of Madrid, 505-471-1562.

PUBLIC BUILDINGS

Nestor Armijo House, Las Cruces

“The house is very important to the community,” says Debbie Moore, president and CEO of the Greater Las Cruces Chamber of Commerce, whose offices occupy the two-story 1866 Nestor Armijo House. “People come see the renovation and talk about how they remember the smell of honeysuckle in the yard and baked goods in the house.” The dwelling’s new life fits its past. Armijo, who purchased the house in 1877, served as vice president of the Mesilla Valley Chamber of Commerce in 1904, and his family occupied the home until 1977, when his daughter Josephine passed away.

It suffered years of neglect, but in 2011, Citizens Bank donated the building to the chamber, which moved into its restored spaces in 2017. Check out the longleaf pine flooring on the ground floor, doors with porcelain handles, and the family’s chandelier. The renovations also included restoring gingerbread trim the Armijos added to give the home a Victorian look—a rarity among adobes—and, of course, planting honeysuckle in the front yard.

If the bed won’t fit … : When Armijo imported an 11-foot-tall brass bed from Europe, workers had to vault an upstairs ceiling in order to give it room.

Nestor Armijo House, 150 E. Lohman Ave., 575-524-1968.

Historic Taos County Courthouse, Taos

Rebuilt in 1934 after a fire, this Spanish Pueblo–style courthouse features 10 WPA-commissioned murals from the Taos Quartet (Emil Bisttram, Victor Higgins, Ward Lockwood, and Bert Phillips).

Historic Taos County Courthouse, 121 N. Plaza (upstairs from the Old Taos County Courthouse Mercado), 575-779-8579.

El Zocalo Tourism and Event Center, Bernalillo

This 1874 refurbished convent triples up as Sandoval County offices, an event center, and a small-business incubator.

El Zocalo Tourism and Event Center, 264 S. Camino del Pueblo, 505-867-8687.

The White Sands Visitor Center was constructed between 1936 and 1938, in a Pueblo Revival style. Photograph by Chad Robertson/Alamy.

The White Sands Visitor Center was constructed between 1936 and 1938, in a Pueblo Revival style. Photograph by Chad Robertson/Alamy.

Visitor Center, White Sands National Park

Pueblo Revival master designer Lyle Bennett planned and worked on this WPA-era building, as well as three staff residences at the park, between 1936 and 1938.

Visitor Center, White Sands National Park, on US 70 near Alamogordo, 575-479-6124.

The Amador Hotel has been a courthouse, post office and more in its lifetime. Photograph by Pictures Now/Alamy.

The Amador Hotel has been a courthouse, post office and more in its lifetime. Photograph by Pictures Now/Alamy.

Amador Hotel, Las Cruces

Originally the Doña Ana County Courthouse (and jail, which once imprisoned Billy the Kid), then a post office, roller skating rink, and hotel, this 1870s building’s ongoing renovation will turn it into an event center.

Amador Hotel, 180 W. Amador Ave., 575-525-1235.

TO LEARN HOW to make adobe bricks, check the websites for Cornerstones Community Partnerships and the Historic Santa Fe Foundation. Some hands-on workshops have been canceled or postponed because of COVID-19.

Various communities welcome helpers to re-mud historic adobe buildings, including the San Francisco de Asís Mission in Los Ranchos de Taos and the San Ysidro Church in Corrales. Cornerstones participates in some of those and posts details on its website.

—Kate Nelson

“IT'S A GREAT building material, it’s absolutely green, and it’s durable,” says Jake Barrow, director of Cornerstones Community Partnerships, a Santa Fe–based nonprofit that helps preserve adobe buildings throughout the state. The Río Grande Valley provides exceptionally well-suited clay that can be formed into stackable bricks joined by a mortar made of mud and water, he says. Master masons can turn those bricks into soaring architecture, but even amateurs can manage a garden wall.

“It’s very forgiving if you follow the basic rules,” Barrow says. “If you make a mistake, take it down, collect the mortar, revive it, and do it over.”

Problems arise when water isn’t guided away from the building, says builder and adobe preservationist Pat Taylor, of Mesilla. When water becomes trapped within the walls, salts build up and turn the bricks into sand. That complicates preservation, but if caught in time, the damage can be reversed.

The effort matters, says Barrow. “This adobe-building tradition is worth preserving. It makes our state special.”

—Kate Nelson