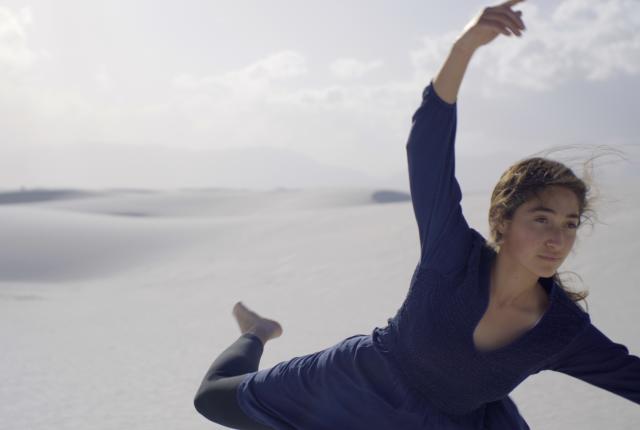

Performers in the National Dance Institute New Mexico film Vastness include Safiya Zavala-Sweet, 17, at White Sands National Park. Photograph by Steven Melendez.

THE IMAGE FEELS LIKE A DREAMSCAPE. Atop the undulating dunes of White Sands National Park, ballet dancers turn, plié, and seemingly float beneath a stunning blue sky. Their bare feet paint brushstrokes in the sugary gypsum.

Isaac Garcia stretches into an arabesque, his lithe form filling the frame of Vastness, a soon-to-premiere film by the National Dance Institute New Mexico. The 17-year-old high school senior from Albuquerque has his sights on a professional dance career—a major leap from his fourth-grade reticence to join in class. “We didn’t realize how expressive he was,” says his mother, Angel Perraglio-Garcia. “If he hadn’t been in an outreach school, we wouldn’t ever have known that about him.”

Vastness marks one of the many ways that NDI New Mexico has performed a pandemic pirouette. Produced with original choreography and music, it places some of its standout dancers in iconic New Mexico locales—White Sands, Abiquiú Lake, and the Valles Caldera National Preserve. The students express creative freedom amid the lockdown and tell a story of hope. New Mexico PBS will host an online premiere April 7 and feature NDI New Mexico on an April 17 edition of its award-winning program ¡Colores!, all leading to NDI New Mexico’s online gala on May 8, which will showcase its pandemic efforts.

Once largely focused on in-person classes at the Dance Barns, in Santa Fe, and later the Hiland Theater, in Albuquerque, NDI New Mexico embarked on a major expansion of digital programs when COVID-19 hit. For years, the organization has brought the performing arts to children who may have no other access to them and who may not even know they like to dance. Leaders questioned how well the new initiative would work, with Zoom-only classes extending students’ already long, online academic days. The answer amazed them.

Elena Garcia, 15, at Battleship Rock, in Jemez Springs. Photograph by Tom Porras.

Elena Garcia, 15, at Battleship Rock, in Jemez Springs. Photograph by Tom Porras.

In previous years, the nonprofit reached around 8,500 students. Beginning in March 2020, it reached 400 more, thanks to online classes. While its in-person offerings have long served kids from ages 3 to 18, during the pandemic the in-school outreach program reached beyond its usual third through fifth graders by adding video classes for all elementary grade levels.

Now in its 27th year, NDI New Mexico tallies 80 employees who provide dance and vocal instruction, make costumes, produce performances, and help raise the $5 million to $6 million a year it takes to keep the program afloat. Throughout its history, the organization has taught more than pointed toes and proper jazz hands. Amid the movement and choreography, students learn core character lessons about working hard, doing their best, never giving up, and being healthy. For many students, these lessons are cemented during a rollicking annual gala stage performance.

“The arts should be accessible to any student or family that wants to be part of it,” says Liz Salganek, the artistic director. “The arts have a way of helping young people be seen and heard. It brings their creative side and their imagination to life, which is very important to their development and their social and emotional health. Especially when we’re going through challenging times, the arts give voice to something that’s hard to put into words.”

Young dancers perform at Española Valley High School. Courtesy of NDI New Mexico.

Young dancers perform at Española Valley High School. Courtesy of NDI New Mexico.

FAMED NEW YORK CITY BALLET DANCER Jacques d’Amboise founded NDI in the Big Apple in 1976. In 1994, New York City Ballet and Twyla Tharp Dance Company alumna Catherine Oppenheimer brought d’Amboise’s kinetic teachings to Santa Fe and co-founded NDI New Mexico. Since then, the organization has served 133,000 children, and the classes have grown up with the students.

Its in-school outreach classes at the elementary level transition to options such as dance teams for middle schoolers, after-school classes, and advanced studio training for pre-professional dancers. Offerings have branched out from the Dance Barns and Hiland Theater to include two-week artistic residencies in towns from Dulce, in northern New Mexico, to Silver City, in the southwest, and from Jemez Springs to Socorro. In the past year, NDI New Mexico programming was offered in 235 public school classes in 25 communities—slightly fewer than its pre-pandemic high of 30.

“One thing I think is beautiful about the two major branches of programming—outreach and classical studio dance training—is the way those two things connect,” Salganek says. “We bring a level of discipline and the high expectations required in traditional dance training; however, it’s built to be accessible to all students.”

Many of the participants may not otherwise be able to take part. Eighty-two percent of the in-school dancers qualify for the federal free or reduced-cost meal program, an indicator of the students’ needs. In addition to free in-school programming, NDI New Mexico has traditionally offered after-school programs on a pay-what-you-can basis. This year, it reduced that to a blanket $5 registration fee.

Albuquerque students put on a show at the Hiland Theater. Courtesy of NDI New Mexico.

Albuquerque students put on a show at the Hiland Theater. Courtesy of NDI New Mexico.

Entire schools and grade levels now sign up for NDI New Mexico’s outreach program. Participation is required, whether the students previously had an interest in dance or not.

Isaac Garcia remembers his fourth-grade skepticism when he started classes at East San José Elementary School, in Albuquerque. “At first I didn’t really understand it, and I wasn’t into it,” he says. “As the classes continued, I fell in love with it.”

As his passion blossomed, Garcia began performing with NDI New Mexico’s dance teams, SWAT (Super Wonderful Advanced Team) and Celebration, and eventually with the organization’s most advanced team, Company XCel. He’s attended competitive summer ballet intensives and aspires to join a training program with a professional dance company after graduation.

This year, the classes for fourth graders at East San José Elementary looked a little different from the ones Garcia experienced. The classrooms were empty. But online sessions kept the students physically active, especially amid the physical restrictions of quarantine.

“Especially in New Mexico, where health outcomes for young people are already in need of improvement, we were coming from a place of empathy,” Salganek says. “We don’t think of dance as the outcome. We see it as a vehicle for the young person to have meaningful activities, relationships, creative outlets, and have their physical, social, and emotional health nurtured.”

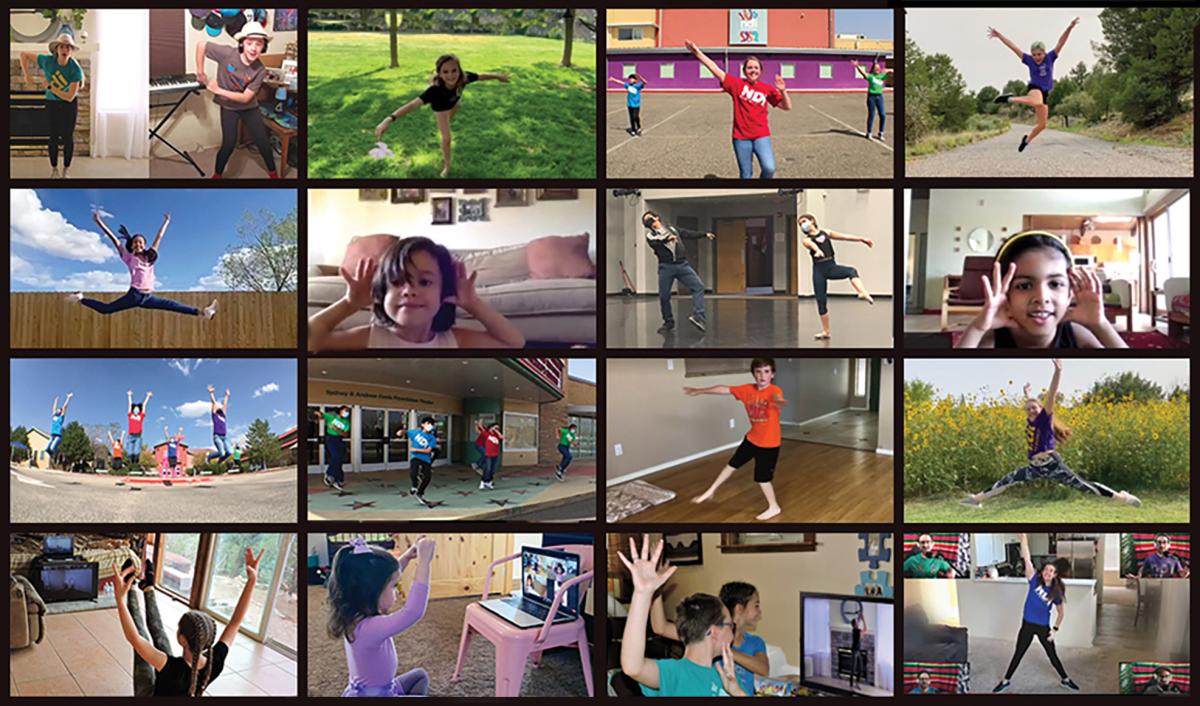

Scenes from a Zoom year. Courtesy of NDI New Mexico.

Scenes from a Zoom year. Courtesy of NDI New Mexico.

ASSOCIATE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR JACKIE BURNS beckons the East San José students to their screens. “Come close and show me your pirate face!” she says. Nearly 20 fourth graders rush forward and turn their class’s Google Hangout gallery into a collage of giggling faces. Some hold up crooked fingers for hooks or place a hand over one eye for a patch. Their mics are off, but judging by the images, a few are growling a piratey Yarr!

That goofy energy is part of NDI New Mexico’s teaching approach, which tempts even reluctant dancers into classes with play and imagery. “It’s an outlet they didn’t know they needed,” Burns says.

Working with fellow artist and piano man Sid Fendley (all NDI New Mexico classes have a live musician), Burns keeps the class moving. She asks the kids to find a small object to leap over during their runs and jumps (“That puppy looks alive,” she cautions one; “let’s pick something that’s not alive”) and to keep their “crispy fingers,” aka jazz hands, as they fly across their screens. They practice chapters (eight counts) of choreography for the end-of-year gala performance to “Brand New Day” from The Wiz, with Burns leading them in a bit of razzle-dazzle.

“You have to be a big kid,” she says of how she instructs other teachers. “You have to want to have fun and be silly. You can’t be afraid to be a blubbering idiot in front of kids and teachers.”

On another day, Burns leads Celebration middle and high schoolers through a three-hour rehearsal. “What feels good to do?” she asks. “The high sunshine kicks!” one volunteers. “The Lindys,” answers another.

They’ve gathered online from bedrooms, living rooms, and garages in Albuquerque, Santa Fe, Española, Pojoaque, and Silver City, to name just a few. In the backgrounds, moms walk in and out with laundry, dads fetch drinks from the fridge, and a little brother wanders aimlessly. Throughout, Burns offers gentle corrections and encouragements: “You can mess up,” she says, “but you can’t give up.”

Fourth graders work with pianist Sid Fendley and a teacher in training as part of the outreach program. Courtesy of NDI New Mexico.

Fourth graders work with pianist Sid Fendley and a teacher in training as part of the outreach program. Courtesy of NDI New Mexico.

Lizzie Moellenbrock, a 15-year-old freshman, joined the Celebration rehearsal from her Socorro living room. Like many of her team members, she was introduced to NDI New Mexico during in-school classes in fourth grade. She’s since danced on the SWAT team and spent four years on the Celebration team.

Moellenbrock smiles throughout the rehearsal, even after an hour of doing Austin Powers–like dance moves on repeat. “Before NDI,” she says, “I was very shy. I wouldn’t talk to anyone. After NDI, it’s so much easier to talk with people. And with dance, I can communicate in a way that I don’t necessarily have to talk.”

Fellow team member Allyson Sandoval, an 11-year-old sixth grader from Española, says the program improved her academics. “I’ve always had good grades, but it’s helped me focus and make my grades even better,” she says.

She’s not alone. A University of New Mexico School of Medicine study found that students who participate in NDI New Mexico’s advanced training programs have higher standardized test scores in writing, math, science, and reading, and boast grade-point averages up to 40 percent higher than their peers. The students are also less likely to have disciplinary infractions or be chronically absent than their counterparts who didn’t participate.

With expanded online classes, students like Moellenbrock have been able to take more classes than ever before. She began attending four classes a week from her Socorro home in addition to rehearsals. Sometimes it’s a challenge, as students deal with internet lags and getting kicked out of sessions. Even so, Sandoval says, it’s worth it. “It’s a breath of fresh air,” she says. “It helps distract you from the virus, school, and everything else that’s going on.”

A Santa Fe performance celebrates important character traits. Courtesy of NDI New Mexico.

A Santa Fe performance celebrates important character traits. Courtesy of NDI New Mexico.

HOW CAN YOU BUILD A CHILD'S SELF-ESTEEM DURING a pandemic and only through a video screen? NDI New Mexico’s leaders and teachers introduced new curriculum focused on mindfulness, grounding, and coping with anxiety.

“You have to find a way to relate to them, find a way to make it personal by using their names, asking their opinions,” Burns says. “We still want them to feel they’re being seen, that they’re not invisible just because they’re on a screen.”

In classes, teachers pause to check in with students, asking them to share about themselves. “Stay onscreen if you love Thanksgiving,” Burns asks. “If you love sports. If you miss your friends.” Other times, teachers offer “warm fuzzies” (compliments) to students about their dance moves or smiles—and encourage the students to share the same with one another.

The end-of-year gala performance, during which 500 students usually dance and sing onstage, also had to adapt to the COVID-19 era. Beyond being joyous affairs, the performances were pinnacle moments for the students.

“We believe and know what the kids are capable of, even if they don’t know it yet,” says Emily Garcia, the Santa Fe outreach artistic director. “When they’ve worked really hard, get to the stage, hit a pose, and have the audience cheer, they get their own sense of accomplishment.”

The virtual 2020 gala invited kids to record and send in videos of themselves dancing at home, which it then used to create video montages. A similar plan caps off the 2021 year. In-school dancers will have virtual assemblies for their families, while advanced students, including those on the SWAT and Celebration teams, and company dancers will present films created with self-taped segments and a few in-person and socially distanced sessions.

Vastness serves a similar goal. The film was the brainchild of Rodney Rivera, Dance Barns’ artistic director and a relative newcomer to a staff that many instructors have served on for decades. When he moved to New Mexico in November 2019, the professional dancer and director marveled at the landscapes, so he turned the state into a stage. Along with fellow choreographers Steven Melendez and Tom Porras, Rivera found inspiration in the light and land. Classical Spanish guitar—courtesy of Associate Music Director Brian Bennett’s compositions—accompanies the featured students.

National Dance Institute New Mexico's Audrie Gonzales-Ellsworth, 14, performs at Abiquiú Lake. Photograph by Steven Melendez.

National Dance Institute New Mexico's Audrie Gonzales-Ellsworth, 14, performs at Abiquiú Lake. Photograph by Steven Melendez.

In the opening scenes at White Sands, the dancers become absorbed in their movements amid the dunes. Then, Native American–inspired flutes and drums back the students as they dance on the water’s edge at Abiquiú Lake, where their movements take on a spiritual quality. Finally, against the verdant backdrop of the Valles Caldera, students run, jump, and relish their connections to the natural world. “Sometimes when we didn’t even say we were filming,” Rivera says, “they were just playing. It came organically.”

The filmmaking team drew inspiration from the students’ spoken-word poetry, which drifts in and out of the film. They speak of their hope for the future and convey a sense of belonging, even amid coronavirus isolation. “They learned that we are all in this together, and we need to be connected,” Rivera says. “What you’re feeling right now might be the same way someone feels 500 miles away.”

The nearly 50 students involved in the film rehearsed digitally at home. Then they gathered, in groups of no more than five people, to film on location during weekends from September to November 2020. Only three students could be on set at a time (along with Rivera and Melendez, the film’s director). Altogether, they captured around 500 hours of footage for the 20-minute film.

Ultimately, Rivera hopes the students who took part learned that the arts are a tool for more than performance. “Creativity is something that you can use to confront your problems,” he says. “Creativity can save you.”

ON YOUR FEET

The National Dance Institute New Mexico film Vastness will premiere on New Mexico PBS’s Facebook page and YouTube channel on April 7 at 6:30 p.m. On April 17 at 4 p.m., the ¡Colores! program will feature the creative process behind the film.

NDI New Mexico offers a variety of classes on dance and fitness throughout the state and hosts a YouTube channel with samples of its programs. Its annual gala hits computer screens on May 8 at 5:30 p.m.