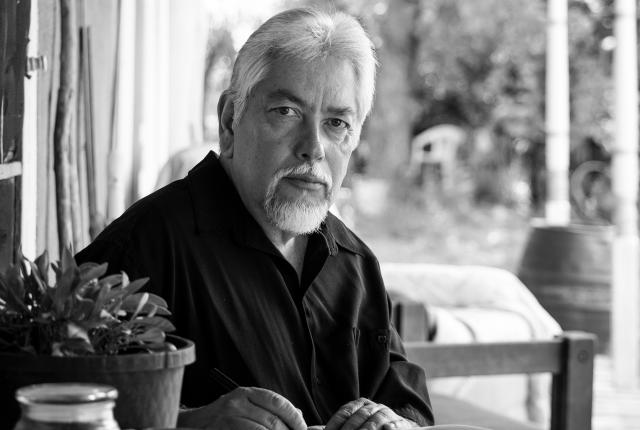

New Mexico Poet Laureate Levi Romero sits under the portal of his family’s home in Dixon.

HOW COME NOTHING IN the great american poetry anthology / reads like the america I know? That question, posed by Levi Romero in his 2008 poem “New and Rejected Works,” is two-pronged. It aims at anthology editors, the gatekeepers who decide which verses are great and American. But it also calls to readers, the seekers who want to see a wider variety of voices represented in literature.

Romero’s spirited, panoramic poetry is rooted in his querencia, the uniquely New Mexican love for home and place. Ever since he was selected as New Mexico’s first poet laureate, earlier this year, his slice of America has started to become much more visible.

He is a lowriding son of the Embudo Valley, south of Taos, where the Río Grande meets the Embudo River and where peaches, apples, corn, and chile thrive alongside a legacy of homegrown writers, artists, and thinkers.

Romero is also an architect and adobe builder, a University of New Mexico assistant professor of Chicana and Chicano Studies, and an oral historian who uses the study of traditional cultural landscapes to fuse structure and story.

As poet laureate, he sees his role as a steward of people’s stories from throughout the state and a guardian of New Mexico’s rich cultural inheritance. These days, he not only is published in anthologies but edits them, too.

In Querencia: Reflections on the New Mexico Homeland, a 2020 collection of essays by Chicanx and Indigenous writers co-edited by Romero, he maps the link between home and identity. Romero remembers the trade route of his maternal grandfather, who traveled from Embudo to Ratón selling vegetables from a horse-drawn wagon.

“My querencia is more than a cornucopia of memories,” he writes. “It has a geographical imprint with stories etched across its landscape.”

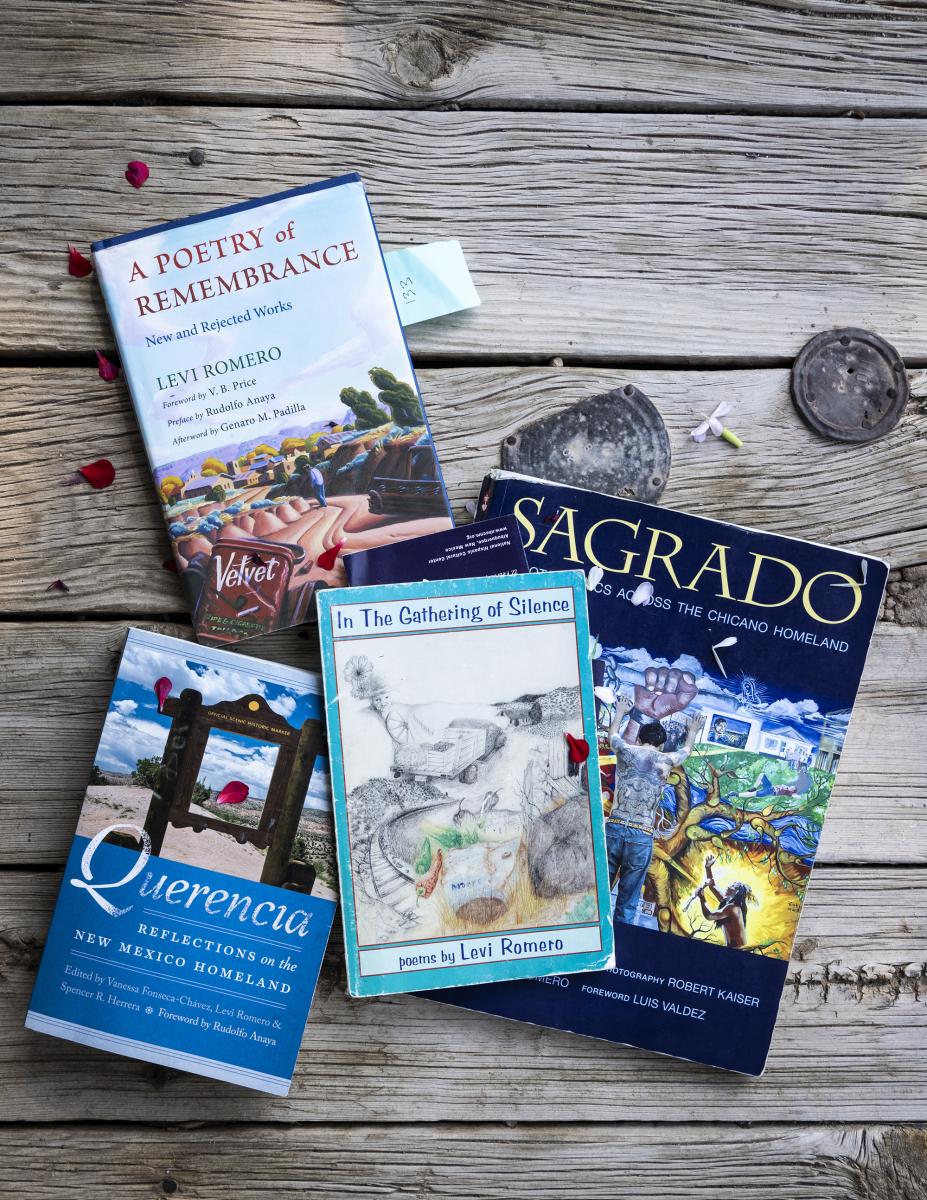

His two poetry collections—In the Gathering of Silence (1996) and A Poetry of Remembrance: New and Rejected Works (2008)—are an immersion in the manito dialect of northern New Mexico Spanish, which coexists on the page with English, Spanglish, dichos (sayings), and snippets of songs and spoken word. Their inclusive bilingualism summons the warm spirits, lively histories, and vibrant memories embedded in Romero’s home valley.

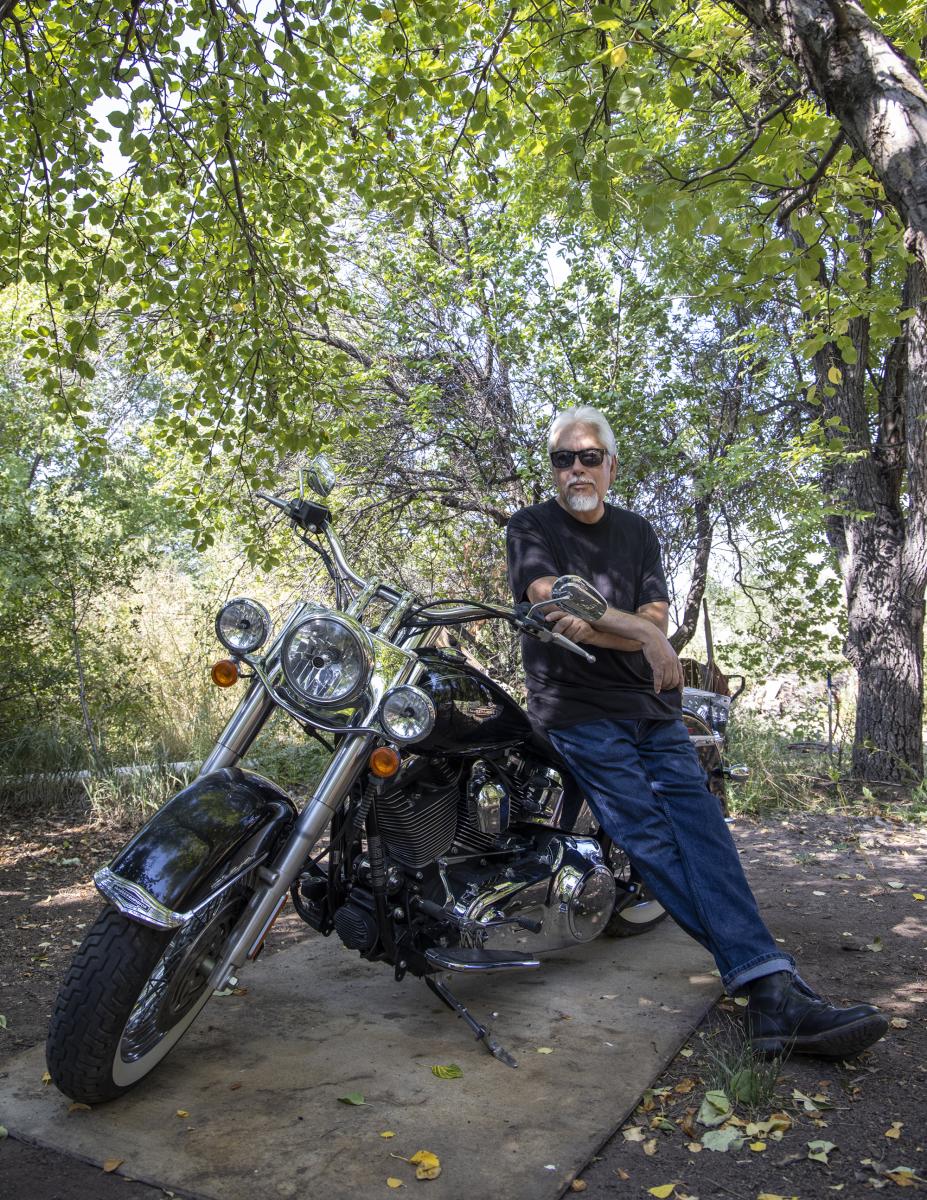

Levi Romero with one of his favorite sets of wheels.

Levi Romero with one of his favorite sets of wheels.

One poem ushers the reader into a conversation about herbal remedios in an Española Walmart aisle. Another is set in the resolana, or conversation space, of FM Hill, the spot outside Dixon where cruisers congregate to get a clear radio signal. The poems introduce a picaresque cast of characters—Romero’s high school English teacher, a man and woman catching up in the unemployment line, his mother reminiscing in a nursing home—who speak in everyday rhythms and lingo.

“My first responsibility is to my community, to my gente and those histories,” Romero explains from his home in Albuquerque’s South Valley.

As laureate, he will spend three years promoting arts, literacy, and education throughout the state by giving readings and community workshops and assembling an anthology of New Mexico poetry. But his main goal, he says, is to yield the microphone to others.

“I am just the vehicle for other poets, other storytellers,” Romero says. “People who don’t even write and may not even read, but who have a story to tell. Sometimes they may already have their main audience with family members. Other times they’re just talking to themselves and nobody’s listening. I feel like it’s my obligation and my responsibility, self-imposed, to move out of the way. They’re in front of the podium now.”

A family alter at Levi Romero's home in Dixon.

A family alter at Levi Romero's home in Dixon.

THAT FINELY TUNED ear for the poetic voices of elders, veterans, hippies, and farmers, among others, was developed around the woodstove at Romero’s great-grandmother’s house in the former Plaza del Embudo. La Academia de la Nueva Raza, a Chicano think tank devoted to cultural preservation, was headquartered there in the 1960s and ’70s, led by writer-activists Tomás Atencio (a primo, or cousin, of Romero’s) and Juan Estevan Arellano.

“There’s a very sophisticated, very well-rooted knowledge that’s there,” says Enrique Lamadrid, a distinguished professor emeritus of Spanish at UNM who was born in Embudo. “That’s all the stuff that informs Levi’s poetry.”

Around age 10, Romero learned to read and write in Spanish from the Academia magazines and books he found around the house. He still marvels at the sustainability of the group, whose members self-published works on a printing press and forged their own distribution networks.

“They would take boxes of their periodicals down to the bar in Dixon,” he says. “They would tell the cantinero, ‘When the guy with the big truck comes by, give him these boxes. And have him take them to Peñasco, and to Mora, and to other towns along his route, and just have him drop them off for us.’ That’s the nature of where I come from.”

Read More: Albuquerque’s new poet laureate champions the area’s cottonwood forest.

Although he tried to drop out of high school more than once, Romero did well enough to earn a scholarship to study art at any public university in the state. He put that off for years, instead choosing to grow his hair long and emulate the soul-searching, motorcycle-powered wanderer played by Michael Parks on the short-lived 1969 NBC show Then Came Bronson.

He tried to move to California but, “like Bugs Bunny, made a left turn in Albuquerque,” where he eventually earned undergraduate and graduate degrees in architecture at UNM.

Throughout his youth, Romero says, he was a closet poet who believed that “cool dudes didn’t write poetry.”

Levi Romero’s books include Querencia: Reflections on the New Mexico Homeland (University of New Mexico Press, 2020), featuring Chicanx and Indigenous writers.

Levi Romero’s books include Querencia: Reflections on the New Mexico Homeland (University of New Mexico Press, 2020), featuring Chicanx and Indigenous writers.

That changed when he signed up for a creative writing workshop at UNM with Navajo poet Luci Tapahonso. The haven that Tapahonso’s class provided from the stress of architecture school “transformed my whole life all the way around,” he remembers.

He became involved in the Albuquerque slam poetry scene of the 1990s and sought guidance from teachers like Sandra Cisneros and the recently passed godfather of contemporary Chicano literature, Rudolfo Anaya.

Anaya was a luminous envoy of New Mexico stories to a wider literary community; Romero is hyper-aware of carrying that torch. As director of two short documentaries about acequia culture and co-author of the 2013 book Sagrado: A Photopoetics Across the Chicano Homeland, he is drawn to an interdisciplinary, out-of-the-schoolhouse approach to education and outreach.

Since the pandemic hit, he’s had to temporarily scrap plans for “a cruise around the state” to promote poetry and literacy, but his schedule remains packed with virtual readings and workshops in English and Spanish. He is working on an anthology of New Mexico poets to be published next year, and he features a different poet every week on his Facebook page.

In all these endeavors, he insists on a looseness of language, a flexibility that channels the voices he hears on the block in Burque or in the shade of the portal outside the Dixon Co-op Market. He loves the fragmentary nature of this kind of storytelling, where punch lines are like artifacts found in the mud.

Some viejito may claim not to remember an ending and tell you to come back later. Or you might miss the beginning of something, tuning in late to the program, because it took you a while to get your dropped 1955 Chevy pickup over to FM Hill.

“That’s what I love about poetry,” Romero says, his voice crackling warmly over the phone. “It’s sort of like an open-ended question and an open-ended answer. A poem has not just one door, but all kinds of doors that lead into all these rooms. And if you do enter a door, then that becomes your space, where you’re going to find whatever is meant for you to find.”

Wheels

By Levi Romero

how can I tell you

baby, oh honey, you’ll

never know the ride

the ride of a lowered chevy

slithering through the

blue dotted night along

Riverside Drive Española

poetry rides the wings

of a ’59 Impala

yes, it does

and it points

chrome antennae towards

’Burque stations rocking

oldies Van Morrison

brown eyed girls

Creedence and a

bad moon rising

over Chimayó

and I guess

it also rides

on muddy Subarus

tuned into new-age radio

on the frigid road

to Taos on weekend

ski trips

yes, baby

you and I are two

kinds of wheels

on the same road

listen, listen

to the lonesome humming

of the tracks we leave

behind

From In the Gathering of Silence, copyright 1996 by Levi Romero. Reprinted by permission of West End Press.