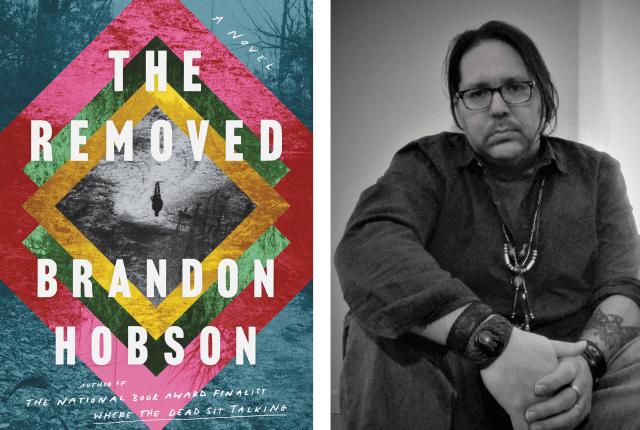

Brandon Hobson's The Removed debuted in February. Photographs courtesy of Ecco and Brandon Hobson.

BRANDON HOBSON'S NOVELS ARE GUIDED BY the Cherokee legends his mother and granny told him, by themes of generational grief, by a deep connection to nature, and by his Indigenous identity. “I was always fascinated by Cherokee history and culture,” he says. “I loved learning more about it.”

Growing up in Oklahoma, Hobson spent humid summers and icy winters in Tahlequah, the capital of the Cherokee Nation. “I was entranced by all the trees and hills,” he says. “One thing I am really interested in writing about is the earth and the land, how the earth remembers history and how it deals with trauma. Just like people, the land reacts and remembers it.”

Hobson now lives in Las Cruces, where he works as an assistant professor of creative writing at New Mexico State University and as a writing mentor at the Institute for American Indian Arts, in Santa Fe. His path to national acclaim took a few turns. After college, he spent more than a decade as a social worker, following the career footsteps of his mother. Eventually, he returned to school, earned a doctorate, and wrote two books, which were published by small presses.

Everything changed when his 2018 novel, Where the Dead Sit Talking (Soho Press), was a finalist for the National Book Award. Set in rural Oklahoma in the 1980s, the story follows Cherokee teen Sequoyah, a foster child looking to belong. “It opened doors and created opportunities for me,” says Hobson, who’s now working on a middle-grade book set in a fictional New Mexico town.

His latest novel, The Removed (Ecco), plays off his experience as a social worker. Sitting at a crossroads between fantasy and reality, the story follows the Echota family, whose eldest son, Ray-Ray, was killed by police. With the anniversary of Ray-Ray’s death approaching, each family member wrestles with the impending anniversary—and their own grief. Interspersed with the Echotas’ present-day trauma, Hobson weaves the story of an ancestor, Tsala, who resisted removal during the Trail of Tears.

“A big part of this book was exploring the ancestral grief that’s continued over 200 years,” Hobson says. “I wanted stories within stories.”

The Removed also reexamines the foster experience, painting it with a different brush in the character of Wyatt, who spends a few days with the Echota family. Eccentric and joyous, Wyatt helps the family heal. “I wanted to break the stereotype of foster kids being sad and show that there are many who are happy and artistic and amazing,” Hobson says.

When he started writing The Removed, Hobson did so with a question in mind. “How do we grieve and how do we heal?” he says. “Chekhov says that fiction should explore questions. We don’t have to give answers, but we should explore.” True to that philosophy, Hobson resists easy answers and opts for a single, solid resolution. “Hope is all we have,” he says.

Read More: Set in a fictionalized Santa Fe, Jamie Figueroa’s debut novel won’t easily be forgotten.