My first week living in Las Cruces, I attended an art gallery opening on the New Mexico State University campus. It had been a hectic few days, as I tried to hit the ground running as a new assistant basketball coach. The Aggies had been to a bunch of NCAA tournaments in a row, and going into the 1994–95 season, I could already feel the pressure to keep that string alive.

One thing I’d learned as a basketball coach: If you want to disappear and find some peace and quiet, hang around the local art scene—basketball fans who were also interested in the arts seemed to be a small club. That first Friday, I figured that lolling around oil paintings and sculptures would settle me down and quiet my mind, which was racing through a long to-do list. There was no way to know this would be the evening my life changed forever.

I was shaken out of my reverie when somebody said, “Are you the Aggies’ new basketball coach?” The bearded speaker turned out to be Robert Boswell. Already a successful writer—Hollywood had just made a movie of his novel Crooked Hearts—Boswell was interested in all the arts. And college basketball. Go figure.

Soon, Boswell and I were friends, and his round kitchen table was the epicenter of our relationship. I was an avid reader, and over the next two years I devoured his novels, as well as the short stories of his wife, Antonya Nelson.

Boz was intensely curious about the inner workings of a college basketball team. And I loved good books. Our conversation often ping-ponged from hoops to fiction and back.

“Think we can we beat the Lobos this week?” he might ask. “You bet. I loved that book by Dagoberto Gilb you gave me. Great stuff.”

“Cool. You think the Aggies will play a zone defense?” And so on, until his wife came in and we could double-team Boz, turning the talk back to novels and short stories.

A year later, I began auditing their fiction classes. But I was not yet ready to make the big leap from coach to writer. By 1998, I wasn’t just auditing classes: I was enrolled, even though I continued to coach. A year later, I was admitted to the graduate program for creative writing , yet I still wasn’t ready to quit hoops: my salary was good, and Lou Henson had come to town as the Aggies’ head coach. He was upbeat and encouraging, and the job became fun again. Still, I knew that, as a hugely successful and happy man who’d been coaching basketball for a lifetime, Henson was a rarity.

College coaching is a high-pressure scramble, but throughout this time, I’d briefly leave it behind and have lunch with the poet Joe Somoza and his wife, the artist Jill Somoza, at their modest home. With Boz’s ideas already swirling in my head, I started thinking seriously about living at the pace Joe and Jill did.

I began working on my own fiction during little pockets of spare time. And I continued to read and reread Robert Boswell’s books (he had only six at that time), trying to figure out what he was up to on the page. Boswell’s novels and stories examined the bonds and strains of American families and friends; superbly crafted, they were simultaneously humane and heartbreaking.

As a regular at Boz’s kitchen table, the writer’s life came to feel normal to me: He’d have another book accepted for publication. Or get another great review. Or another idea for a new novel. No big deal. And by then his wife, Antonya Nelson, was gaining national renown. Her work was included in Best American Short Stories, and her name appeared on the New Yorker’s “20 Writers for the 21st Century” list. Making it as a writer, getting published—well, it gradually felt like what one was supposed to do. You might label it a midlife crisis, but to me, the call of the writer’s life in Las Cruces felt organic, natural. No crisis. I quit coaching in 2000. (In the most modest buyout in the history of college sports, Coach Henson made sure that athletics covered my two years of already-affordable in-state tuition.)

In 2001, NMSU hired the award-winning poet Connie Voisine, a lovely and talented lady, to teach poetry in its Creative Writing program. I finished graduate school and went to Ireland to coach professional basketball—a laughable idea, sure, but I figured it would be easy. I came back home with the worst record in the country, but also with the manuscript that became my first book, a memoir about my time in Ireland: Paddy on the Hardwood.

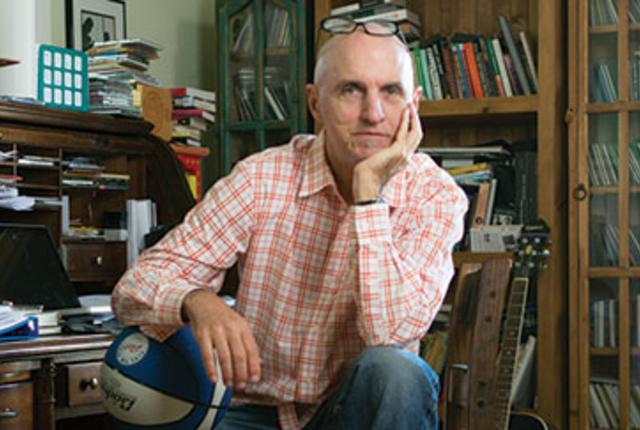

Today, 10 years after returning from Ireland, I still work at NMSU, but now I coach in the English Department. And the biggest factor in my successful switch from basketball to books was not talent, or intelligence, or determination.

I owe most of it to the Las Cruces literary community.

Here’s why: While the town is very much off the beaten path, it is crawling with aspiring and published writers who have found a home here. New Mexico’s southernmost city boasts a vibrant writing scene—both at NMSU and around town.

Why such a terrific literary scene in Las Cruces? It’s the configuration of small-town accessibility, gorgeous weather, the stunning and inspirational Organ Mountains, a diverse and open-minded population, a few lively reading series, and the state’s first Masters of Fine Arts program for fiction and poetry.

But to really understand how Las Cruces became a destination for writers, you have to retrace its history.

Keith Wilson was a Korean War vet who came to Las Cruces in 1967 to teach at NMSU, after studying with poets of the Black Mountain school. Graves Registry is his book about Korea, and, having published many volumes of poetry, Wilson has to be considered the founder of the local literary scene: He was named the city’s first (and last) Poet Laureate by the city council.

In the 1970s, Wilson and his colleague, the poet Joe Somoza, got the notion that NMSU needed an authentic creative-writing program.

Somoza, who was born in Spain, worked with Wilson to bring some of America’s best-known poets to Las Cruces for readings. For accommodations, they unrolled sleeping bags on couches in their own homes, and they were imaginative about how to pay visiting writers. At one point they convinced the physics department to chip in for honoraria. Wilson and Somoza did everything but hold car washes—though they did host a couple of bake sales.

Fiction writer Kevin McIlvoy came to Las Cruces the 1980s. A fearless risk-taker on the page and a tireless worker for the community, he later spearheaded NMSU’s petition in Santa Fe to establish the state’s first MFA program in creative writing. He also founded the Desert Writers group at the local senior citizen center, a workshop in existence now for over 30 years. If Boswell and Nelson could be credited with teaching me the aspects of craft, McIlvoy might be called the inspiration: He’s a testament to the idea that a committed individual can truly transform a town. He juggled a half-dozen projects at once, all of them fueled by his generosity.

For two decades, McIlvoy, Boswell, and Nelson had quite the reputation for their rigorous and hands-on approach to teaching fiction. Published writers, successful professionals, and even graduates of the prestigious Iowa Writers Workshop flocked to southern New Mexico to study the craft of writing fiction. The NMSU graduate program produced a surprising number of published authors.

Joe Somoza retired from NMSU, and he’s become a sort of literary antihero—he doesn’t care about being published, let alone being famous. But he still composes wise poems in his scruffy backyard. In New Mexico, any man’s land can become an Eden, and so it is with Somoza. Connie Voisine and I got married in the summer of 2003. There was no debate about which church or country club would host the ceremony. We asked Joe if we could hold the event in his back yard.

Somoza’s Buddha-like presence seems timeless, but the Las Cruces literary scene evolves. Boswell and Nelson left NMSU to teach in Houston one semester a year—but their permanent home is still here, and they reside in Las Cruces each fall. Boswell has enjoyed a dramatic resurgence of late: His last short-story collection, The Heyday of the Insensitive Bastards, got gushy praise from Oprah. His new novel, Tumbledown, got a rave in the New York Times Book Review. And Nelson just had yet another piece selected for Best American Short Stories. They’ve written 20 books of fiction.

A few years ago, Craig Holden, the acclaimed author of such novels as Four Corners of Night and The Jazz Bird, migrated to Las Cruces to teach at NMSU. He’s stayed long after his teaching appointment ended, raising his four children and plotting his next literary thriller. With Boswell and Nelson gone, Holden would provide a model for my next small steps: His exceptionally tight and efficient style is hypnotic and enticing. Holden’s novels are like a Taos ski run, but maybe one you’re not quite experienced enough for; he’s a paradox, a master of acceleration in this decidedly laid-back town.

Next, one of my favorite nonfiction writers, the legendary Charles Bowden, decided to make his home in Las Cruces. Bowden’s latest book is Murder City, a bluntly honest take on the brutality just south of the border, in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico— 40 miles and a world away.

The matriarch of the entire Las Cruces scene is the multitalented, American Book Award–winning Denise Chávez. Another former NMSU professor, she’s a novelist, short-story writer, playwright, actress, and author of the enticing and soon-to-bereleased novel The King and Queen of Comezón.

Nobody entertains visitors like Denise Chávez. In fact, the Border Book Festival (which she founded) attracts writers and readers from all over the country (borderbookfestival.org). This year’s fest will take place April 25–27; as of this writing the lineup was still being formulated, but maybe you’ll spot last year’s PEN/Faulkner Award winner—and Las Cruces native—Benjamin Alire Sáenz, who directs the creativewriting program at the University of Texas–El Paso, just south on I-10.

Her festival’s headquarters can be found just east of downtown, at the Casa Camino Real, in the Mesquite Historic District. Don’t be in a hurry—Chávez has plenty to offer in her homey adobe, which overflows with artifacts from old and New Mexico, rare books, and, of course, pan dulces and cafecitos for anyone who steps through the door.

Plainly, Las Cruces has accumulated quite a remarkable literary history. But what does the future hold? I sometimes wonder who might be the next great writer to emerge from literary Las Cruces. We don’t think about it too much, because we’re busy writing. I’m lost at work on a new novel. And, like any writer, I need somebody to discuss my new manuscript with, to think out loud to. But Boswell and Nelson reside in Las Cruces only in the fall months.

Still, I know their house sitter, who, like me, became a writing student at NMSU in his 40s. So I find myself at that round kitchen table a couple of nights a week. This student and I talk about our favorite books and writers, just as Boz and I did for nearly two decades. I think it’s good karma to sit at that table, even when Boz isn’t around, because that’s where he did some of his best writing.

Yesterday morning I went over to the Boswell-Nelson home and had a cup of tea with their house sitter.

“Boswell will be moving back in five days,” he reminded me. “Antonya two days after that.”

The round table was covered with stacks of books.

“You need to tidy up?” I asked.

“I think I need to keep writing,” he said, and we downed our tea. ✜