JUDGING BY THE MAN'S DROOPED HEAD and slumped shoulders, the bottle of tequila on the table dealt a knockout blow. Carved from wood, in the style of a Spanish colonial bulto, the figure hardly seems a saint in his la vida loca T-shirt. But if God loves a drunk, could this lost soul be an angel unaware? Luis Tapia isn’t saying.

“I want people to study the piece and judge for themselves,” he says. “I had a basic idea and started with the table. Then I did a chair. Then the gentleman. I didn’t know I was going to pass him out. It’s how it ended up.”

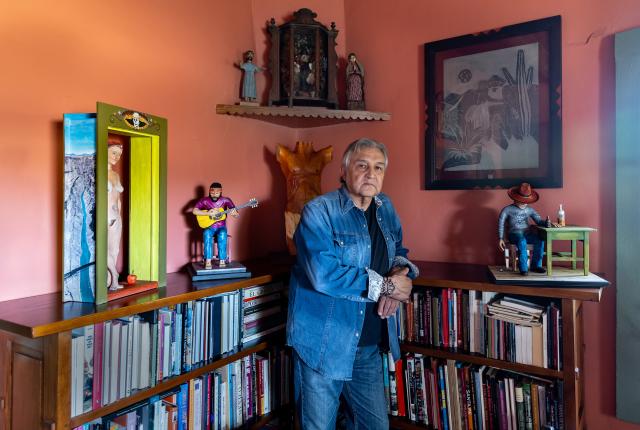

The completed work, Homage to a Good Bottle of Tequila and a Beer Chaser, is one of the few Tapia pieces on display in a La Ciénega adobe that is packed with other artists’ paintings, masks, sculptures, ceramics, and furniture. It sits near Tapia’s The Last Musician, a guitar player whose hands and feet bear the stigmata—the wounds from the nails that held Christ to his cross. The musician wears a rose-printed bandanna in place of a crown of thorns, and a T-shirt painted with a highway intersection representing a cross.

“It’s the ‘Crossroads Tour,’ ” Tapia exclaims, his face beaming.

Only a miracle will keep the sculptures inside the 250-year-old house that Tapia, 72, shares with his wife, author Carmella Padilla. Where he once sold traditional bultos (statues of saints) for $35 to $50 apiece at Santa Fe’s annual Spanish Market, his latter-day works of lowriders, gangsters, immigrants, and laborers—some biting, some humorous, all complex—now grace museums throughout the nation. Collectors latch onto them nearly as quickly as he finishes them.

In October, Tapia was named one of the 15 inaugural recipients of the Joan Mitchell Fellowship, an award for which artists from all over the United States are nominated anonymously by people selected by the Joan Mitchell Foundation. Named for the late, celebrated painter, the fellowship recognizes standouts who hone the cutting edge of painting and sculpture, supports them with $60,000 over five years, and advises them on legal, financial, and marketing matters. (In a New Mexico coup, Santa Clara Pueblo artist Rose B. Simpson also won a fellowship.)

“Luis is extraordinarily groundbreaking,” says Tey Marianna Nunn, director of the Smithsonian American Women’s History Initiative and former chief curator at the National Hispanic Cultural Center, in Albuquerque. “He was among the first artists to really embrace the Spanish colonial tradition but take it where it needed to go in contemporary times. And he mastered it. He studied the collections. He knows them. He blazed a path for other artists to follow.”

At an age when he could be forgiven a slower schedule, Tapia resolutely puts in at least five hours a day, seven days a week, in a studio set far enough away from his home to have attained a sanctified status. “Of course, you’re always thinking of art,” he says. “But working on it, that’s my meditation, that’s my livelihood, that’s my religion.”

AS A 1950s KID in Santa Fe’s then-rural Agua Fría Village, Tapia was more concerned with getting by than with soaking up his culture. Raised largely by his grandmother while his widowed mother worked extra jobs, he attended schools that banned speaking Spanish and showed up at San Isidro Church because his grandmother took him there “by the ear.” He saw colonial art on its walls, but a coming wave of preservation and restoration efforts had yet to bring back the luster of those and other religious artworks in northern New Mexico. It never occurred to him that he would become a leader in that movement, too, his skill at reviving centuries-old pieces among his greatest gifts.

“I didn’t realize what my culture was about,” he says. “In the last 100 years, they were taking away our language. That’s a stripping of identity. Our arts were going by the wayside. In church, I saw all this art, but I didn’t see it.”

In his teens, he linked into the Chicano movement, which motivated him to learn more about his culture, including its art. At 21, he taught himself to carve and began exploring the meanings of various saints and colonial techniques by visiting museum collections, talking with other santeros, and devouring books, despite the difficulty posed by his dyslexia. He studied the stern images along with their repeated elements—Christ in the bloody gore of his crucifixion, San Isidro with his staff, Santa Barbara in her tower.

In his studies, he forged a connection to the lives of Spanish and Mexican colonists who were isolated, dependent on meager farms, and grounded by faith. In the early 1970s, he won a spot at Spanish Market, when “a majority of the santos were by the Córdova or Ortega carvers—non-painted. A couple of guys were painting them, but then aging the paint to look old.”

But Tapia’s research taught him that the faded paints on classic santos had started out as vibrant colors. When he introduced those original hues at the market, he drew the organizers’ scorn. One of his final offenses: daring to use Old Testament scenes, primarily one with Noah’s ark. Such depictions are now common at Spanish Market, but Tapia’s ark drew him a swift ouster from the fold.

He then metaphorically wandered an artistic wilderness, honing his skills while showing at markets in El Paso and Salt Lake City. At the latter show, he met a woman who connected him with the Smithsonian, which invited him to participate in a two-week celebration of American craftspeople in 1976.

The exposure this gave to his hand-carved saints and furniture changed his trajectory among collectors and curators. Soon he was immersed in the museum world as a Chicano artist making works that grappled with issues of civil rights, the border, farmworkers, and poverty—all of which, to him, led straight back to biblical times.

“Why were Joseph and Mary running?” he asks. “Why was Jesus born in a barn? I thought, I know a Joseph, but I call him José. I know a Mary—María. They have a kid named Jesús.”

Tapia’s art changed. He began decorating all sides of his pieces, demanding that they be viewed in the round, unlike traditional santos, which were placed on an altar or in a nicho or simply shoved against a wall. His characters took on new narratives. He depicted José (Joseph) with slicked-back hair and tattoos. Jesús took on the tasks of a landscape worker and pushed a wheelbarrow that held a globe of the Earth. His take on the Virgin of Guadalupe delivered a commentary on his own place in the Southwest borderlands: Thorned cacti imprisoned her, the sun-bleached bones of an immigrant lay at her feet, a chorus of faces covered her back.

Inspired by the saints in his mother’s car, he crafted wooden dashboard altars, some nearly life-size, including Cruising Hollywood: Homage to Magu, which honors the life of his late friend Gilbert “Magu” Luján, a founder of the Los Angeles art collective Los Four. (The piece includes an ashtray with a Bic lighter and a marijuana pipe.)

“Religion takes different roads,” Tapia says.

ONE DAY, WHILE DRINKING BEER with metal artist Bill Van De Valde, his friend and neighbor, Tapia spoke a thought that he soon wished he hadn’t: “What do you think about cutting a car in half?” Van De Valde said it could be done, so the two pulled a 1963 Cadillac from a junkyard.

Splitting the 17½-foot-long icon of American steel lengthwise was only the first of many engineering headaches, which included dropping it to lowrider status and rebuilding the frame so it could roll. He coated it in white paint and then covered it in a tattoo-like maze of blue cacti, skulls, dice, a Zozobra head, and the words FANTASE CITY LIMITS.

While working at the National Hispanic Cultural Center, Nunn fought to add the halved car to its collections. The day A Slice of American Pie finally rolled into the building stands as one of her favorites. “There’s a visual vocabulary of New Mexico on that car,” she says. “He’s so sure of who he is that he can be that fearless in his work. That’s a superpower.”

Among a generation of younger santeros influenced by Tapia’s blend of old and new is Vicente Telles, a South Valley native whose work is included in Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of Malinche, at the Albuquerque Museum through September 4. “When I was just starting out, I saw one of Luis’s dashboard altars and thought, Oh, this is cool,” Telles says. “He could have been comfortable doing what he originally did, but he had to make a bold decision. That inspired me.”

Tapia still harnesses his superpower the old-fashioned way. No computer. No social media. No grand blueprint for the next five years. Ask him what’s next and he’ll shrug. “Tomorrow. That’s as far as I go. I’m sort of content with where I’m at. It’s led me to where I am. What more would I need?”

Well, there are those cars in the driveway. A ’64 Ford Falcon convertible. A ’51 Studebaker. A ’52 Chevy sedan delivery wagon. “They all used to work,” he says, a bit ruefully. And there are those five-hour days, seven days a week. Perhaps the cars’ day will come? As usual, Luis Tapia isn’t saying.

“I feel I’m doing the best work I’ve ever done,” he says. “I challenge myself every day to make my work better. How I carve, how I paint, how I think. I have more control over my materials and myself. I have a stride in my work that’s been constant for many years. That’s my future.”

A Cut Above

Learn more about Luis Tapia’s artistic journey in Borderless: The Art of Luis Tapia (Museum of Latin American Art, 2017) and on his website, luistapia.com.