THE STATE SENATE PRO tempore’s office, located in the Capitol building basement in Santa Fe, contains a wall of photographs of holders of that position. Among them is a 1931 black-and-white of a bald man with a walrus mustache: Oliver M. Lee, the only one who ever stood trial for killing a child.

Eight-year-old Henry Fountain and his father, Albert, a lawyer and politician, vanished near White Sands National Park on February 1, 1896. Their mysterious disappearance has haunted New Mexicans ever since.

At the time, the elder Fountain was best known for representing Billy the Kid in his 1881 trial for murdering a sheriff. Weeks before his disappearance, Fountain secured indictments against Lee—a political rival—and 22 others for cattle rustling in southeastern New Mexico. He had brought Henry along to court in Lincoln. Some say his wife, Mariana, thought Henry’s presence would protect the lawyer from the accused thieves. After all, what monster would kill a little boy?

The Fountains left Lincoln for their home in Mesilla on January 30. They never made it.

A few facts are known: At Chalk Hill on February 1, Fountain told a stagecoach driver that three men seemed to be following him. The driver urged him to turn back toward Tularosa, but Fountain pressed on. Later, searchers found blood-soaked patches of ground in the same area and Fountain’s buckboard wagon nearby.

The slaying of Henry was the only murder accusation against Lee that reached trial, though he was suspected in other cases. “Oliver Lee didn’t do much to dispute these accusations,” says Joe Lewandowski, board director of the Tularosa Basin Historical Society. “Lee seemed to believe that if people thought you were capable of murder, they’d leave you alone.”

Investigations by the Pinkerton Detective Agency and Doña Ana County Sheriff Pat Garrett both pointed to Lee and associates. In 1898, Garrett secured murder warrants for Lee along with James Gilliland and William McNew, who were also accused in Fountain’s cattle-rustling case.

The case became a battle between two rival political bosses: prosecutor Thomas Catron, of the notorious Santa Fe Ring, and defense attorney Albert Fall. Both later served as U.S. senators, with Fall also becoming Secretary of the Interior. (Eventually he was convicted on bribery charges in the Teapot Dome scandal of the early 1920s.)

Prosecutors decided to try Henry’s death first. “The big reason was so if more evidence came to light—specifically finding the Fountains’ bodies—they could come back and retry the case,” says historian Corey Recko, author of Murder on the White Sands (2008). “[And] since no one would have sympathy for the killing of a child.”

“Modern forensics could have helped solve the case, both in terms of evidence found at the crime scene and blood splatter discovered at the site.”

Without the victims’ bodies, the prosecution faced a steep climb. “Modern forensics could have helped solve the case, both in terms of evidence found at the crime scene and blood splatter discovered at the site,” says Michael McGarrity, a former Santa Fe County Sheriff’s Department detective turned crime novelist. “But without the bodies of Fountain and his son, it still would remain difficult to successfully prosecute.” The jury took less than 10 minutes to acquit Lee and Gilliland, and prosecutors dropped all other cases tied to the Fountains.

McGarrity, who weaved a version of the Fountain case into his 2012 novel, Hard Country, says the fascination with these deaths is intergenerational. “Descendants of Oliver Lee and others still call New Mexico home,” he says. “It remains a hot topic for discussion.”

FACT-CHECK

FACT-CHECK

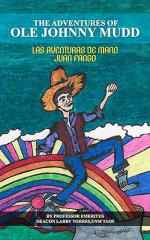

Was Johnny Mudd a real cowboy?

No. “Ole Johnny Mudd is a composite character based on the cowboy from the tall tales sheepherders told in northern New Mexico,” says Larry Torres, a longtime University of New Mexico professor who collected the folk stories in The Adventures of Ole Johnny Mudd. “The sheepherders didn’t have book-learning, so they based the stories on common sense to pass down from one generation to the next. It was a different way of learning than we have today.” —Jennifer Levin

Lee’s reputation as a gunslinger didn’t rest solely on the Fountain case. Many believed he was behind the 1882 murder of neighbor Walter Good amid a water-rights dispute. Lee was charged but never tried. In 1894, another neighbor, Francois-Jean “Frenchy” Rochas—the man who likely built Santa Fe’s “Miraculous Staircase” at the Loretto Chapel—was shot and killed in his home. Lee was widely suspected but never charged for that one.

By the time he died at age 76 in 1941, Lee had reinvented himself as a politician. In his memoir, former Territorial Governor George Curry praised his friend’s “sterling character.” Lee’s former ranch was even turned into a state park bearing his name.

The Fountains’ memorials are more modest. A historic marker sits on US 70 near Chalk Hill. And at the Masonic Cemetery in Las Cruces, a stone reserves two plots, in case their bodies are ever found.

➤ Here’s where you can investigate some of our state’s most enduring questions.

SEE FOR YOURSELF

The 640-acre Oliver Lee Memorial State Park, with 44 campsites and one group site, is known for its namesake’s restored ranch house and its sweeping views across the Tularosa Basin. “There are three different hiking trails, two of which are easy,” says park manager Kate German. “The other trail ascends 3,100 feet in five and a half miles, an 11-mile round trip.”