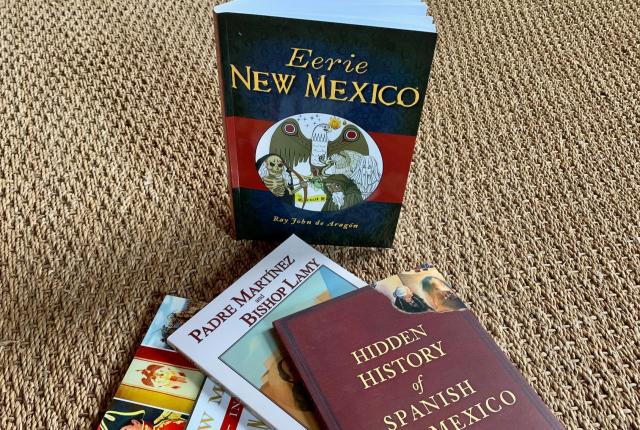

Ray John de Aragón most recent book, Eerie New Mexico, is filled with folktales and spooky stories. Photograph by Kate Nelson.

AS AN ARTIST AND AUTHOR, Ray John de Aragón delves into his northern New Mexico heritage for inspiration. The historian and folklorist, whose work has been published in numerous books, explores legends ranging among bolas de lumbre (balls of fire), body snatchers, witches, and scary ghosts in his most recent book, Eerie New Mexico (History Press, 2020). We asked the Las Vegas, New Mexico, native to tell us about his work.

What role did folktales play in your youth?

When I was a little kid, one of the favorite pastimes of our family and neighbors was telling folktales about experiences they had. As a little kid, I was enthralled. We would gather in the kitchen, and they would talk about things that were supernatural, paranormal. To me, that was beautiful. Eventually, my mother would tell me I had to go to bed. But my bed was right next to the kitchen. I would listen to the rest of their stories through the wall and be scared to death of ghosts and spirits.

I imagine you heard about La Llorona, the Wailing Woman who drowned her children and is haunting rivers and arroyos for new ones to steal?

We lived next to the Arroyo Manteca. Mom always told me, “When water comes down from the mountains, it rushes through there, be very careful. La Llorona might catch you, and we’ll never see you again.” Me and my friends, when we were six or seven years old, we’d go out to the arroyo and look at the ditch and underneath the bridge and think, What is La Llorona? What’s she look like? We’d think, There’s nothing here. One day, a torrential rain came down from the mountain, and that’s when I finally understood what my mother was talking about. That’s the whole aspect of La Llorona: You have to be careful in those channels.

So it was a scary story with a moral, right?

If you look back in history, even during ancient times, the stories they told were about how to live your life, how to be kind. There’s always some basis of truth along the line.

Sometimes, curanderas were thought of as brujas, or witches. But they were important healers, weren’t they?

My great-grandmother was a curandera—a medicine woman, a healer with herbs in our culture. She studied all of the herbs, Spanish and Native American, to help cure people. In New Mexico, a curandera was highly respected. My great-grandmother saved many people during the 1918 influenza. She would be out there late into the night treating people.

When you went to the University of New Mexico, how did your professors react to these tales?

At the university, they usually kept passing on the same stories they found from other writers. There was a lot of repetition and distortion by those who wrote the original versions. I found it interesting that here were stories that had been written down 100 years ago and perpetuated from that. As a researcher, I went by what I’d heard in my family. Also, I got good advice from Howard Bryan, an author who also worked for The Albuquerque Tribune. He would always say, “Never ever go by what anyone else has written. You have to go deeper, talk to more people.”

Read More: La Llorona. Skinwalkers. UFOs. Haunted hotels. When the world turns weird, we turn pro.

Read More: New Mexico has more than its fair share of the wacky and weird.