CHRISTMAS IN NEW MEXICO IS UNIQUE. It is a time of celebration and a time of memories.

When I was a child, my mother’s preparations for Christmas meant a week’s work in the kitchen. Pots of posole would bubble on the stove, the plump tamales wrapped in their corn husks steamed in the pressure cooker. The aroma of these foods made from corn, the sacred food of the New World, pervaded the kitchen. There were also desserts.

Plates of empanaditas made with fruit and sweet meats were piled high. The brown-sugar-and-nutmeg smell of the biscochitos filled the house. These were just some of the traditional foods prepared to celebrate the birthdate of Christ.

It was my father’s job to scour the countryside for a piñon tree. It was a treasure trip for me as I accompanied him in search of the green tree which would grace our simple home. It would be decorated with an old and frayed string of lights, and bright streamers of cloth my mother sewed. My sisters would add the icicles and the angel hair.

On Christmas Eve we hung our stockings on the stout branches of the tree. In the morning the stockings would be stuffed with hard candy, nuts, and fruit. There were always plenty of apples and dried fruit, the bounty of the harvest from the farms of my uncles in Puerto de Luna.

Oranges were a favorite, but they were expensive and available only if my father was working.

Christmas Eve meant bundling up at 11 o’clock at night to make the long trek into town to celebrate la Misa del Gallo, Midnight Mass. The long walk into town was also a time for contemplation. Under the starry sky of the New Mexico llano, the open plains country, it was the family unit which made its way to church. My mother led, we followed close behind, my father came after us.

That walk rekindles memories of my childhood. The night was cold. Over us sparkled the mystery of the universe, the stars of the Milky Way. Once, long ago, one star lighted the way to Bethlehem. I learned then that to celebrate the religious spirit one had to be attentive. Each person could renew the spirit within, but each had to make an offering. My mother’s offering was her belief in the birth of Christ, el Cristo. My father offered the green tree, the symbol of life everlasting, the tree of life itself. And we offered the long, cold walk to join the community of the mass.

Read more: At Acoma Pueblo, the celebration of Christ’s birth unites the community.

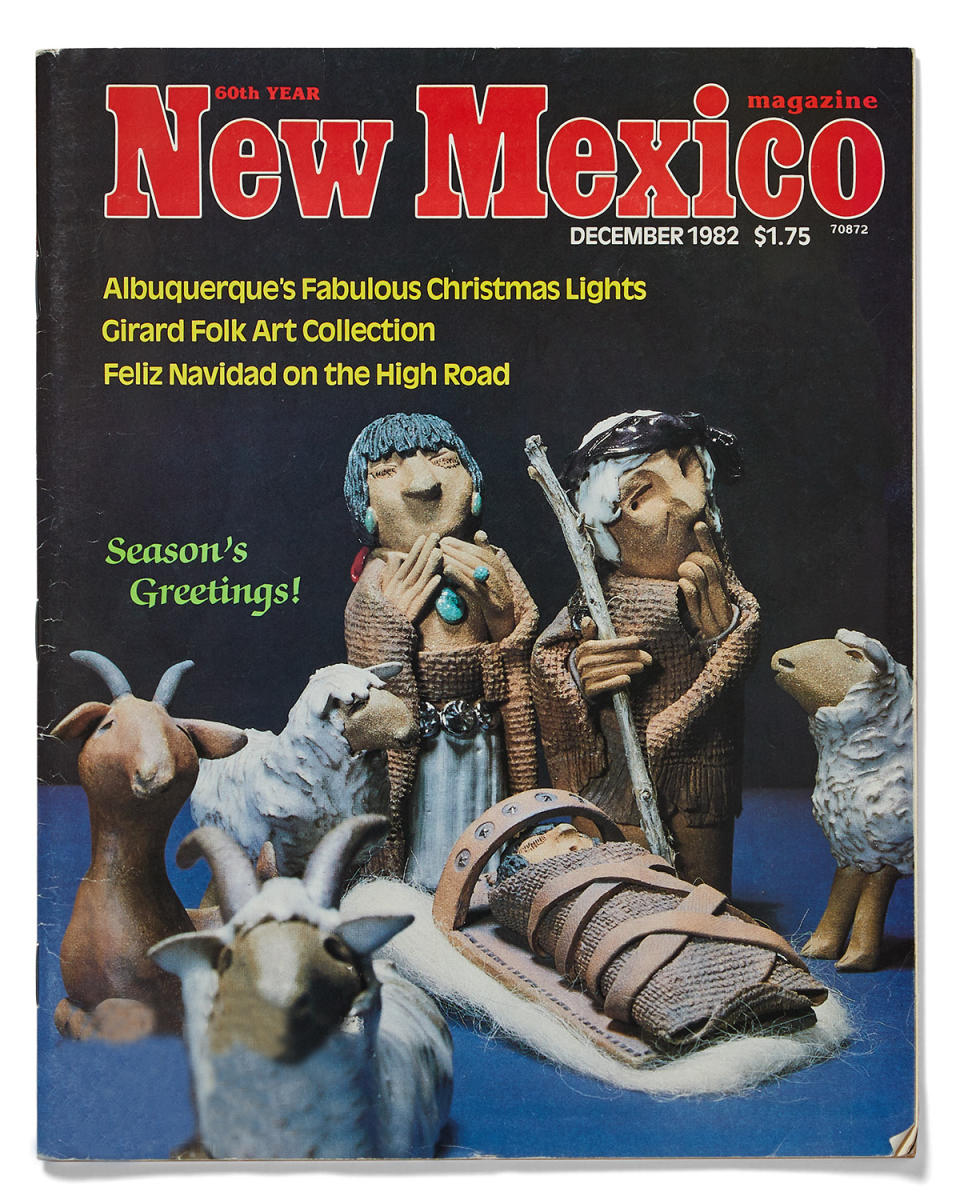

About the cover

A shepherd standing beside Mary quiets his animals so they will not disturb the baby Jesus in the scene arranged with figures from a Marnie McCarthy Pueblo Indian crèche.

It is that individual and communal offering which cannot be packaged in the modern department store.

After Mass and the cold walk, there was hot chocolate and biscochitos, and then blissful sleep.

In the morning we would awaken to search in the stockings and to open gifts, gifts we usually made ourselves for one another, because there was little money for store-bought gifts. Gifts from the store meant shirts, pants, and underwear for me, maybe a pair of gloves if the fingers were showing in the old pair. For my sisters, more clothing, curlers, and prized nylons—as bobby socks gave way to womanhood.

Then I would run out to join my friends to visit the houses of our neighbors. Our shout was, “Mis Crismes! Mis Crismes!” We asked for and received the traditional gifts of Christmas, much as the trick-ortreaters do today on Halloween. Our flour sacks bulged with candy, nuts, and fruits when we returned home.

Later in the morning the family would start arriving, brothers from afar, aunts and uncles, and the entire potpourri of padrinos and madrinas, compadres and comadres, cousins, friends, the whole extended family.

For a child lost in the wonder of the celebration everyone was a welcome sight. They all brought gifts. If the piñon season had been good that fall, someone would arrive with a gunny sack full of piñones, those sweet, little nuts we would crack and eat in front of the stove as we listened to the stories. Another might bring carne seca, jerky to be cooked with red chile from the ristra hanging in the pantry. Perhaps someone had been working in Texas, and his truck would be loaded with oranges and ruby red grapefruits, gifts from el Valle de Tejas where some went to make a living.

Then we would compare gifts, and my cousins would ask, “What did Santo Clos bring you?”

Now I know that our Santo Clos was the Santa Claus we knew at school, where we also decorated the classroom tree and acted in the annual Christmas play. The stockings and the Perry Como Christmas songs on radio were the influence of the Anglo culture filtering into our way of life. The cultures were interacting, exchanging customs, and yet each group could still retain its own ways, borrowing from each other and forming the mosaic of celebration which Christmas has come to be in New Mexico.

At the center of the celebration was the tree. For my father it was important to have it ready on December 21, the day of the winter solstice. This was indeed the tree of life, and its importance and the importance of the day were fixed in the religious nature of the Indians of New Mexico, as it has been fixed since time immemorial in most of the cultures of the world. The shortest day of the year reminds us all that the sun has reached the end of its winter journey. It will return northward to renew the earth, but for one day it hangs in precarious balance.

On this day in ancient Mexico, and throughout the Americas, sacrifices were made in honor of the sun, the life giver. Incense was burned and sprigs of green were gathered. Ancient man understood his relation to the cosmos. For him the race of the sun was a mystery to be celebrated. One had to be attentive to the workings of the planets and stars, as one had to attend to the working of the spirit within. I wonder how much of that awe we have lost today.

Read more: North of Santa Fe, a water mill continues a tradition and brings a community together.

Our child’s Christmas in New Mexico was not fixed on expensive toys; there were no video games to distract the spirit and exhaust the mind with nonsense. We gathered together to celebrate two ways of life, the Christian and the Indigenous religious spirit which came to us through the traditions founded in ancient Mexico. Our Christmas day was not intent on football games, but on listening to the history of the families who came to visit. They brought many stories. The kitchen was warm and filled with good food, and after we ate we listened to the stories.

My child’s Christmas was a celebration because it was a sharing. Out of that past I have evolved the rituals which are important for me to celebrate. I decorate with lights the piñon tree near the entrance to my home. I make sure it is lighted on the night of December 21. It also serves me well for Christmas.

But there are so many celebrations to share in as the year draws to a close. When it is possible, I go to Jemez Pueblo on December 12, dia de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe. The Matachines dances at Jemez are among the most exquisite I have ever witnessed. The color of the earth is red, the hills are dotted with junipers and pines, and above the pueblo loom the dark Jemez Mountains. As one approaches, the pueblo appears serene and quiet, then one hears the violin of the fiddler. It is time to hurry to the plaza where two brightly colored lines of dancers move to the music.

The dancers wear the ornate, colorful corona, the headdress. The rattle of hollow gourds fills the air as the dancers move back and forth to the lively, repetitive strains of the fiddle. The drama is a mixture of a pueblo step and a polka, more Spanish than Indian. The Malinche, the little girl in white, symbolizing innocence to me, dances with the old Abuelo, the grandfather. Near her lurks the dancer dressed as El Toro, the old devil. This dance was brought by the Spaniards to the New World, now it is danced both in the Hispano villages and the Indian pueblos of New Mexico. It is a unique and enthralling mixture of customs.

For me a visit to Jemez is a good way to start the season of renewal. An hour or two spent visiting with friends at Jemez and sitting in the winter sun while the dance drama unfolds can remind the most depressed of spirits that man is still attentive to his religious needs. All of the homes are open, strangers are fed. The tables are heaped high with posole, meat, chile dishes, tortillas and Indian bread from the homos, pies, and biscochitos. Imagine what a better life this would be if all the homes in the cities and suburbs enacted this noble sense of community.

Another enthralling experience is to be at the Taos Pueblo on Christmas Day, but it could be any one of the other pueblos, because they are all celebrating. It is the end of a season, a time of dancing and singing. But in Taos on the afternoon of Christmas Eve the Mass is celebrated, then the people come pouring out of the church in a winding line. I have been there when my friend Cruz pulled me into the procession to weave around the faroles, stacks of criss-crossed piñon wood which are burning and lighting the way of the celebrants. And what are these faroles, or luminarias as they are called today, but a reflection on earth of the stars which light the way, the star which guided the shepherds to Bethlehem. A reflection of the sun and the light within.

Those roaring fires at the pueblo rekindle the memory of the stars I contemplated as a child. The sweet perfume of the burning piñon rises into the dark, cold sky. So it is with the votive candles in the church. The smoke rises with its message for harmony and peace.

On Christmas Day the deer dance is often held, a dance both for the Taoseños and for their guests. One has to be attentive to brave the sharp cold of the winter morning. Then from the direction of the blue Taos Mountain the cry of the deer is heard, the frozen spectators stamp their feet and wait eagerly. The cold is numbing, but worth the effort. The deer dancers unite the elements of earth and sky and make glow the deep, religious nature of the pueblo.

In Albuquerque, now my home, there are other old and lasting rituals to be enacted. Even in the city the barrios preserve their traditions. Los Pastores, an old miracle play which originated in Spain, is a favorite.

There is hardly a barrio or a village which doesn’t have its version of this nativity play. Each of the shepherds in the play represents a vice, and when Bartolo, the laziest of the group, is finally converted, the audience rejoices.

Las Posadas is another favorite miracle play, and one of the oldest plays from the western world continually re-enacted in the New World. The story tells how Joseph and Mary sought an inn, a posada. Those who play the parts go from home to home, seeking shelter, and in a series of supplication and answer between the procession and the householder, they are refused. The procession moves to another home, singing carols, until finally they are admitted, and all the guests are fed. There is singing and great rejoicing.

There is something beneath the ritual which must be the real message. Even when Las Posadas are not enacted as a play, the idea of welcoming the stranger to the feast persists. That is why so many people met in my mother’s kitchen in those Christmases of long ago.

Time changes the customs in small ways, it does not dim the memory. Now the faroles are not the stacks of piñon wood to be lighted, they are votive candles placed in paper sacks with sand at the bottom. When we were children the brown paper bags were saved not only for sack lunches, but a pile grew all year long so we would have enough sacks to use as luminarias for Christmas.

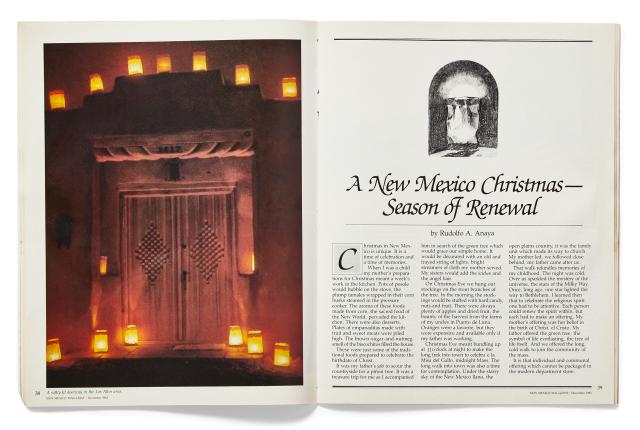

The luminarias are a traditional New Mexico custom. Hundreds adorn homes, walkways, and the curbs of the streets. On a cold Christmas night even the most humble home is transformed as the candles flicker and glow in the dark.

Caravans of tourists fill the streets in the evenings to view the symphony of lights which glow to announce that in this home there is posada (shelter). Neighborhoods become united as they gather in community effort to decorate their homes and streets. Candles and paper sacks are shared, even if today they are bought at the store, and the children vie to light the candles. More than one enterprising company is now making electric luminarias. Perhaps the important thing is that the lights continue to be lit.

In our memory we remember that it is important to light the fire at the end of this season, whether the fire be the yule log or the luminarias of New Mexico. A fire shall light the way, just as the evergreen will remind us that life will renew itself.

Deep within the celebration of these customs which are still enacted, there lies the flicker of hope. Christmas celebrates the birth of Christ, it is also the celebration of the ending of the year, the cycle of the sun. Now the sun will return north and the days will grow longer, and those who were attentive to this mysterious spirit of renewal will be fulfilled.

quotable

“Albuquerque on Christmas Eve becomes the place of enchanted lights. In a state famous for its Christmas lights, Albuquerque puts on a show unequalled in kind anywhere. .… No photograph can capture the impact of Albuquerque’s splendid luminaria displays where entire neighborhoods—houses, walls, and walkways—are set aglow.”

—from “Albuquerque’s Enchanted Lights,” a photo-essay by Bob Casper

december 1982 calendar

All-Month

Christmas Show, Nuestro Teatro, Albuquerque

12/2-12/4

L’egg’s Women’s Basketball Tournament, Las Cruces

12/3

Nutcracker Suite, Civic Auditorium, Los Alamos

12/4

Torchlight Parade, Red River Ski Area, Red River

12/4 & 12/5

Second Annual Red Rock Balloon Rally, Gallup

12/4-12/12

Las Posadas, San Miguel Mission, Santa Fe

12/10-12/31

Los Pastores del Valle de Mesilla, Las Cruces

12/12

Our Lady of Guadalupe Feast Day, Jemez & Pojoaque pueblos

12/19–12/23

Christmas in the Palace, Santa Fe

12/26

Turtle Dance, San Juan Pueblo

12/31

Gala New Year’s Eve Pops Concert, Convention Center, Albuquerque