FOR NEARLY 11 MONTHS OF THE YEAR, New Mexico’s seasons march along with the ordered serenity of cloistered nuns in procession, but in October their progress becomes a “revel of frenzied Bacchantes.” Hills and mountains, tiring of the monotony of summer verdure, deck themselves in glowing, golden raiment. Lower slopes and canyon walls wear rose and flaming red and deep maroon. The skies are lapis lazuli and mountain lakes are ultramarine. Rivers run with a dancing tempo; even the air is intoxicating. Then it is the gold leaf trail that calls, and only a clod could fail to respond.

Traced on the map, the gold leaf trail looks like a toy balloon with a dangling string, which means that you may cut them apart and content yourself with either the balloon or the string. If you have a few extra hours, don’t deny yourself the pleasure of enjoying both. The point where the string ties is Taos. Then, starting out to the right, or southeast, the road bears the numbers 64, 38, 3, and 64. It sounds like a football signal, and it holds as much promise of thrilling excitement. On 3, the trail, or string, leads southeasterly to Las Vegas, and down it you ride abreast with beauty, history, and romance.

Legend, rumor, and historical fact hover in the air above this part of New Mexico like the great cumulus clouds that float about Mount Wheeler’s summit. You may not notice them, but knowing they’re there adds much to the trip. … Follow the trail through Taos Canyon and you hear, in fancy, the rattle of covered wagons starting the trek to faraway Missouri, laden with pelts of beaver, marten, and otter from New Mexico’s mountains and streams. You hear too, the creak of wooden wheels as a Mexican carreta bumps along the rough road over which you are now spinning in comfort. You may turn aside to let a band of phantom trappers clatter by, their voices raised in lusty song as they near civilization after long, lonely months of isolation.

Not a word of all this will the chipmunks that dart across the path, or the large jays that scold from the tall pines, or the deer that peer through the thicket tell you. They are accustomed to the company of shades [spirits] whose presence they would never think of revealing.

If you are lucky, a breathtaking sight awaits you [in the Moreno Valley]. Acres and acres of fringed gentians of a blue so rich and vivid that it has long been the delight and the despair of artists stretch like a wondrous carpet at the foot of a sloping curve. Seeing the gentians is like being kissed by the fairies in your cradle—it is a very special gift from a kindly fate. The season must be exactly right, or the gentians simply don’t bloom. But though the gentians may be lacking, there is still color in abundance. Oak, sumac, and wild cherry glow in their autumnal foliage, and here and there, like red beads sewed upon nature’s dress are the bright hips of the wild rose.

Farther along the road you encounter real ghosts, for at Elizabethtown and neighboring spots are buried the hopes and dreams that died when the mines were closed. Skeletons of machines that roared when placer mining flourished are now gaunt and grisly reminders that men once labored and laughed as they searched for the gold that was to make them rich. Fires burned and candles twinkled and children prattled behind windows that now stare blankly at passersby. There is nothing quite so desolate as a ghost town.

It is a very real man and not a specter, however, that stands on the gravelly bottom of the streambed. He is panning for gold as men did 50 years ago. Verily, the prospector is the perennial optimist!

You turn once more to the beauties of the trail that continues to play hide-and-seek with the Carson National Forest. You have passed the azure expanse of Eagle Nest Lake, where, no doubt, the fishermen in the party threatened to desert. To the west you have seen Taos Cone, at whose feet nestles Blue Lake, more than 11,000 feet above the seas. The mysterious rites of the Taos tribe were held here recently. Now there is no sign of life on the steep mountain slopes except where shy conies [rabbits] dart in and out among the rocks. There is no sound but that of marmots whistling saucily, if somewhat eerily, in the vibrant air.

There’s never a dull moment on gold leaf trail, for, like a giant roller-coaster, it is a series of ups and downs. The ascent of Red River Pass is as gorgeous as a triumphal procession. You arrive at the top, the blood singing in your veins. You will want to take a few minutes out here just to stand in a field of trailing arbutus and convince yourself that its dark green glossy leaves and glowing red berries are real. There are huckleberry bushes, too, and while you look a dusky grouse whirrs up from them in startled flight.

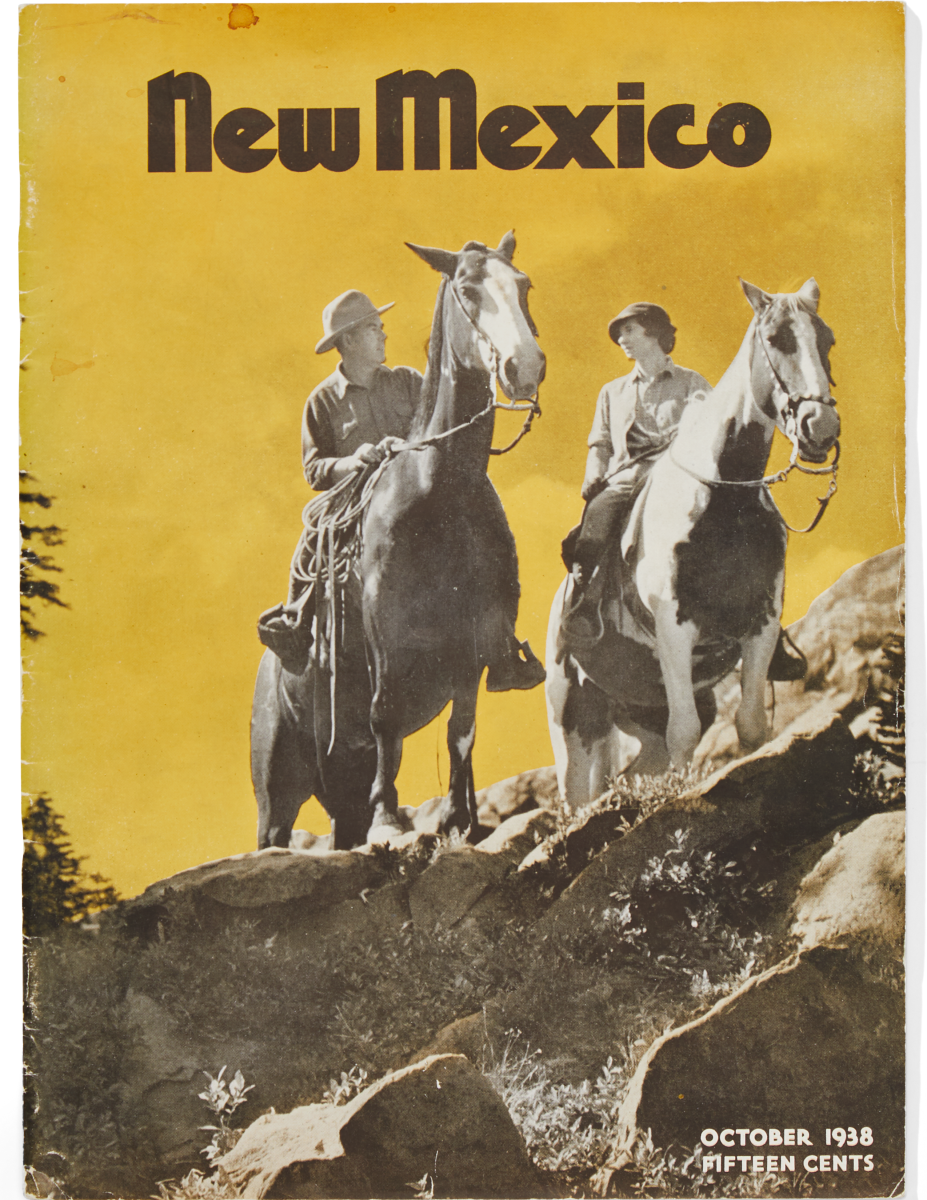

On the Cover

On the Cover

“Roads to Romance,” by H. Armstrong Roberts

It is here that the road leaves the old Spanish grant, through which you have been riding for miles, and starts its breathtaking descent. When you feel that nothing but a miracle can save you from shooting out into space, a sudden sharp turn takes you safely onward. This happens again and again; but fortunately, there are thrills and chills but no spills on this trail.

Can you imagine how a tiny bug might feel when it stands at the top of a wall tapestry and starts the crawl to the floor? You’ll know after this ride! For the canyon walls are tapestries of incomparable beauty. Evergreen conifers form the background of varying verdure upon which sumac, canyon maple, and oaks embroider patterns of scarlet. Quaking aspens prick out designs of purest gold. As you pass, they toss their leaves like ancient Roman coins in your path where they lie tarnishing under passing wheels. Filtering sunlight turns the dull rose of the wild cherry’s foliage to Tyrian purple. Color combinations wrought only by a season gone berserk imprint themselves upon your mind. Incredulous, you turn for another look. But the scene has changed; receding wall and distant peak now seem richly overlaid with gold leaf, as if Old World artisans, having completed their mediaeval cathedrals, were laboring with loving skill upon our “templed hills.”

Such a riot of color leaves a feeling of stimulation which lasts until long after the little town of Questa is passed. There is gold, gold everywhere, a veritable treasure vault of nature. You are grateful for the quietude of Taos. After a rest, however, you are ready for the trip down the string of the balloon—Highway 3, which joins 85 a few miles from Las Vegas.

Leading southward, the road crosses a tiny stream with an impressively long name, Río de Don Fernando de Taos, and swings on through old Ranchos de Taos. It pauses before the ancient church. Who that comes to New Mexico would think of leaving without seeing this venerable edifice? It is true that modernity with its ruinous touch has invaded even these sacred precincts, and many of the original features have been removed or overlaid with garish things of recent manufacture. But, due to the influence of one very wise man, the old altar remains behind the new main altar, and someday it may emerge from its temporary obscurity and take the high place among Southwestern art treasures which it so richly deserves. You tread the wooden floor softly, for beneath it lie the bodies of many early communicants, and you look with appreciation at the ancient walls. They [the artworks] were brought from Spain or from Mexico for the worshippers in this little New Mexico settlement.

But October days are too golden to be spent indoors, and the road is calling. It seems in a hurry to reach the first slopes of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Despite its urging, you tarry along the Río Pueblo. The stream is gentle, playful, invitational. Its water is so clear that the pebbles on the bottom look like golden nuggets under crystal. A plump little gray bird, its wings outspread, skims the surface with a funny combination of flying in the water and swimming in the air. It is all as colorful and fanciful as a Disney color cartoon, and you half expect to see a fuzzy green caterpillar stand on its tail at the end of a red leaf and sway to music. But the dipper, or water ouzel, continues to bathe without temptation from the bank, and the car leaves Tres Ritos and begins to climb.

Upward you go through avenues of trees that might have grown on King Midas’s estate, so golden are they. Beneath them lies an occasional bronze feather, for here wild turkeys feed. Brown bears, too, make this forest their home, and your coming may startle one as he goes about the business of overturning stones with his great strong claws to see if, maybe, some big black ants or fat grubs will reward his efforts.

Color! Color! Every tone in the chromatic scale is here. And then, before you are ready, you have crossed the divide and are dropping down on the other side. A beautiful spiral turn, a small stream and you are passing through the old town of Holman. Beside the gate before an adobe casita stands a tiny girl in blue-striped overalls. She smiles at you shyly and buries her face in the fur of a gray kitten that nestles in the curve of her throat and, just as you pass from sight, she gives you a farewell wave.

Farms flash by. You have a blurred impression of shocks of golden grain, and you are puzzled by the fact that these fields, like those near Taos, are divided into long narrow strips definitely marked by hedge-like rows of standing grain or tall grass. You are really reading a record of births or deaths as accurate as if written in the family Bible. For the entire place was originally owned by one man, perhaps an old Spanish grant, more probably by homestead or purchase right. At his death the land was divided among his children—four children, four smaller fields. Later these were in turn divided for younger heirs, until now many of the fields look like long narrow aisles. There are not many houses, and you wonder idly where so many owners might dwell.

Occasionally you see a brown adobe home sprawling lazily in the autumn sunshine. On its flat roof are piles of squash and melons, pumpkins and beans, ripening and drying for the winter’s food. At another place the squash and melons have been cut into long strips and flung across the clothesline to dry. Here, too, are pieces of fresh meat which the dry air and sun turn into flint-like “jerky.” This, with frijoles seasoned with a pod of chile from the numerous strings that cascade like strands of rubies from the housetop, will make a dish fit for a king.

The air is full of the humming of drowsy bumblebees. You hear the querulous call of sheep and see the black-and-white flash of magpies. You sink back luxuriously and are quite prepared for Mora with its shady retreats and its cross riding to the bluest of skies. It was over 100 years ago that men first came to this spot to work the deposits of mica that still abound. Later, Father Salpointe, a French missionary, came with cross and book; nearly 74 years ago, a tiny schoolhouse was built. The schools are still under the guidance of the Sisters, although a man has charge of the manual arts, and many lovely and authentic copies of early Spanish chairs, tables, and beds are created in the small shop. The girls card wool, tinted with old vegetable dyes, and weave coverlets just as those first settlers did when the bell called them to worship in the chapel of Saint Gertrude.

An atmosphere of antiquity pervades the place. Soft-voiced nuns sit in the shade of a venerable linden tree or walk the quartz-bordered path that leads to the shadowy grotto wherein stands a statue of Saint Joseph holding in his arms the Holy Infant. Birds nest atop that first small adobe building which still stands sturdily and serves as a garage and washroom.

A short distance from the school is what was once the Watson Hotel, built on a part of the old Mora grant. It is still a hostelry. In the low-ceilinged front room stands an old black square piano brought by oxen across the plains in the 1860s. Here, too, is a gilt-framed mirror that has reflected the daily happenings about it for more than two centuries. Below it is an onyx-topped table with a frame of solid brass and a pair of old majolica vases.

The 1938 calendar is a rude intrusion, but it serves to remind you that time passes. Reluctantly, you leave. The road dips and turns; it carries you somewhat hastily across the Cebolla and the Sapello; it brings you at last to Las Vegas. From here the roads, like those ancient ones which all led to Rome, lead back to the workaday world. Gradually the gold leaf trail descends, slowly flattens out and becomes just a highway with a number. But now, golden memories go with you.

OCTOBER 1938 CALENDAR

First Week

Annual Navajo Indian Fair, Shiprock Navajo Indian Agency

First Week

Rodeo, Tularosa

10/1 & 2

Bi-state Fair, Draft Horse and Mule Show, Clovis

10/3 & 4

Feast Day of St. Francis of Assisi

10/4

Annual Fiesta and Dance, Nambe Pueblo

10/7

Football, UNM vs. Colorado College, Albuquerque

NM Normal College vs. Ft. Lewis School, Las Vegas

10/9–16

New Mexico State Fair, Albuquerque

10/21 & 22

Daughters of the American Revolution Convention, Roswell