Illustration by Ryan Johnson.

THE ESSENCE OF CHRISTMAS can be served in one bowl. The bowl is small and white. It holds freshly made red chile, the “fancy kind.” That means instead of using chile powder or store-bought frozen, my mom took the dried pods, blended them with hot water, and mixed the liquid with shredded pork, salt, and garlic, using the pork juices to flavor the chile in a combination that creates one of the best tastes on earth.

It is the perfect Christmas meal, one my mother prepared every Christmas Eve—even the one we almost spent apart. Like those in many families, the customs of my youth transformed as I grew, married, and began my own family. The tradition of my adult years over two decades of married life was to head to Taos Pueblo for Christmas Eve. My husband, son, and I, along with his many relatives at the pueblo, came to watch bonfire flames lick the sky as people carried a statue of the Virgin Mary through the village in procession.

The Christ child does not get lost at Taos Pueblo on Christmas Eve. The lights are plentiful, and good cheer is abundant. We would eat together, at his aunties’ house by the village, and catch up on events of the year, then return to his family home to light our own small bonfires and open presents. Late at night, we would make our way home to Santa Fe, wondering if the farolitos by the road in Velarde would still be flickering.

One year, though, I was torn. My mother was frail and growing more so. Either I would spend Christmas Eve with her in Santa Fe—without my son and husband—or I had to leave her alone. She told me to go. My mom always encouraged me to be off, enjoy an adventure, tend to my family, or see a new corner of the world. That year, as much as I hated not seeing my son open presents, I knew what I had to do.

I stayed.

Illustration by Ryan Johnson.

WE WENT TO EARLY MASS at Santa Maria de la Paz, in Santa Fe. It’s a children’s service the afternoon of Christmas Eve, with plenty of singing, pageantry, and that sincere belief in how a child, one to be born that night, could save the world. Then it was back to Mom’s house, where the chile simmered on the stove, a big pot for just two people. On a plate nearby were stacks of empanaditas that she and I had made—well, that she had fixed and I had fried—our Christmas specialty ready for whoever might stop by over the holidays.

All the elements of my childhood celebrations came together: Food. Family. Faith. Fire.

There was the traditional food—chile and empanaditas, the sweet meat turnovers that can make a meal by themselves. When I was a child in Las Vegas, New Mexico, we expected the arrival of dozens of cousins, many aunts and uncles, and friends from town.

Then, the offerings were more varied than our simple bowl of red chile. Posole on Christmas Eve, with red chile nearby to add color and flavor; fresh tamales, usually from my Auntie Rita. The sisters split the Christmas work. My mom made the empanaditas and, when needed, sopaipillas, while my aunt did tamales. Each family added their own chile, posole, or enchiladas. The idea was to have enough food so that anyone who stopped in could be fed.

My grandma Celia was the bizcochito maker, turning out dozens of the sugar-cinnamon-anise cookies, so light and delicate they dissolved on the first bite. I can see her hands rolling out the dough, using a small shot glass to cut the cookies, then fluting the edges by hand, her fingers moving so quickly it was hard for the eye to keep up.

My job was to dip the cookies into a sugar-and-cinnamon mix, which I did while standing on a small stool over the kitchen table as my grandma shaped the cookies.

Read More: Holiday cookie recipes from Rude Boy Cookies in Albuquerque.

Family was blended into those foods of Christmas. Not only the immediate relatives—the ones who came and ate, dropping off their own baked goods or small presents—but the ones who had lived before, who had taught my grandma, mother, and aunts to cook these foods.

Making empanaditas is not a task for the meek. The process is laborious, with the cook first preparing the roasts—pork and beef—and adding the spices, nuts, and raisins.

In our house, my mother cooked the meat first. Then came the shredding of the roasts through a metal grinder, my brother and me fighting over who would be chosen to push the meat through, relishing how big chunks went in and small pieces emerged. Then my mom would add the other ingredients and leave them simmering overnight.

Her job as a child was peeling the beef tongue, a task she hated. As a grown-up, she removed tongue from her recipe, fiddling with the ingredients to make it just as savory without the need for little fingers to peel away skin.

The flavors merged by morning, and then Momma would make the masa and begin the process of folding the dough around the meat. She’d plop a big spoon of filling in the middle of the dough, bring the edges together, and close and twist them into a seal. Then, with hot oil bubbling at the perfect temperature, we fried the empanaditas, watching so that the dough turned a perfect golden color.

We kids secretly hoped for the seals to open—at least one or two—because those empanaditas were rejected and we got to share them. Bite too soon (it was so tempting to do so) and we would burn our tongues.

Illustration by Ryan Johnson.

FAMILY WAS ESSENTIAL for cooking these traditional foods. Assembling empanaditas and tamales takes time. And people. Women came together to make those treats or spend an afternoon baking cookies. In those kitchens, with women helping one another, little girls learned important lessons—discovering how to measure the flour by hand, without a cup, what the secret to a fluffy sopaipilla is, or how to flatten a tortilla with a rolling pin fashioned from the top of a broom handle. We would fight over who got to drop a piece of dough into the bubbling hot grease, the test to see if it was time to start frying.

These foods were made by families and for families, shared with love or packed carefully in coffee cans to be mailed to Auntie Thelma in California or Uncle Roger in Chicago. Family mattered across the miles, with connections renewed through food.

Right after Thanksgiving, whether we were home in Las Vegas or after we moved to Texas—where these traditions continued amid much curiosity from our new neighbors—my uncle or aunt would call (on Sunday, when long-distance rates were cheap) to try to sniff out when the goodies would be in the mail.

The tradition continued every year, even that first year in Texas after my mother barely survived ovarian cancer. She liked to think of my brother opening his can in Lubbock, or my aunt in California, or, later, her grandchildren in cities throughout Texas. Those empanaditas and bizcochitos, of course, found me in San Angelo, Texas, and in Bradenton, Florida, where I worked for newspapers in my twenties. I always found new popularity at Christmas.

When I was little, those food deliveries were done in person. We would take a plate of goodies each Christmas season, in the manner of a formal afternoon call, across Railroad Avenue in Las Vegas to visit my grandma’s brother and his wife—Uncle Jess and Aunt Mary.

Food would be exchanged. Aunt Mary would serve coffee, but not in the kitchen, where, on other days, she and my grandmother could sit and chat for hours. No, at Christmas we sat in the living room, chilly even with the heat going, and the grown-ups would exchange news while we kids fidgeted.

It was a seasonal ritual, a time to share the riches of the kitchen. We would repeat the visits to other relatives throughout the season, sometimes dropping off goodies at the door if time was short, other times sitting and chatting. Family members would return the favor, stopping by our house on Seventh Street to leave their specialties—fudge, cookies, and other sweets. These connections, made over food and with family, were a touchstone of each Christmas season.

Illustration by Ryan Johnson.

IN THE BACKGROUND, as daily life continued, there were other preparations for the holiday, starting with marking the season of Advent. Remember: All of this was happening before the Christmas season stretched from Halloween into January. In those simple days of the 1960s, with only three television stations, one car per family, and no expectations of Christmas loot beyond a few presents, we didn’t need that much time to celebrate properly.

During Advent, my Catholic family prepared for the coming of the Christ child. That was both the tradition and the belief. This took the pressure off our parents to spend into debt and removed our focus from presents under the tree, placing it on the true meaning of the season.

We went to Mass, watching each Sunday as another candle in the Advent wreath was lit. Our house had its small Nativity set up, with the spot for the baby Jesus kept empty until Christmas Eve. One of our family traditions was to build ever more animals for the shepherds to watch.

It brought out my grandma’s crafty side. Using plaster of paris, we would make sheep, occasionally cows and camels, and paint them so that, before the humble manger, all animals stood in awe. Or so we thought. Our camels never came out quite right.

Many years, we would spend part of Christmas Eve baking a birthday cake for the baby. My mother never wanted us to forget whose birthday we celebrated.

Read More: Start your year on an adventuresome course with a January that’s made to order.

Always, we needed to find a Christmas tree. Some years, my dad would bring a tree home from the auto body shop, a result of bartering. Other times we would head up Gallinas Canyon and chop our own. (As an adult, I embraced that as our annual tradition. We now chop trees almost every Christmas, a carryover from childhood for both me and my husband.) However we found the tree while growing up, we did so very late in the season. Not always so late as Christmas Eve—which is when a proper tree should go up, as that’s the first day of the traditional Christmas season—but certainly not so early as the day after Thanksgiving.

Our trees were traditional New Mexico selections, somewhat lacking in branches and needing extra decorations to cover the bare spots.

We were a tinsel family. Once our tree was decorated with colored lights and shiny silver, I would sit on the couch, just watching the lights, until someone told me to go to bed. I loved the colors. I loved them so much that one year all I wanted for Christmas was a tree of my own. My mother was not impressed and told me to choose something else. Somehow, that Christmas, even though I could see the stairs and spied no one carrying anything into my second-floor bedroom, Santa managed to smuggle in a tree to leave alongside my bed, decorated simply and smelling divinely of the woods.

I had my very own tree. And my faith in Santa—despite my advanced age of eight—was confirmed.

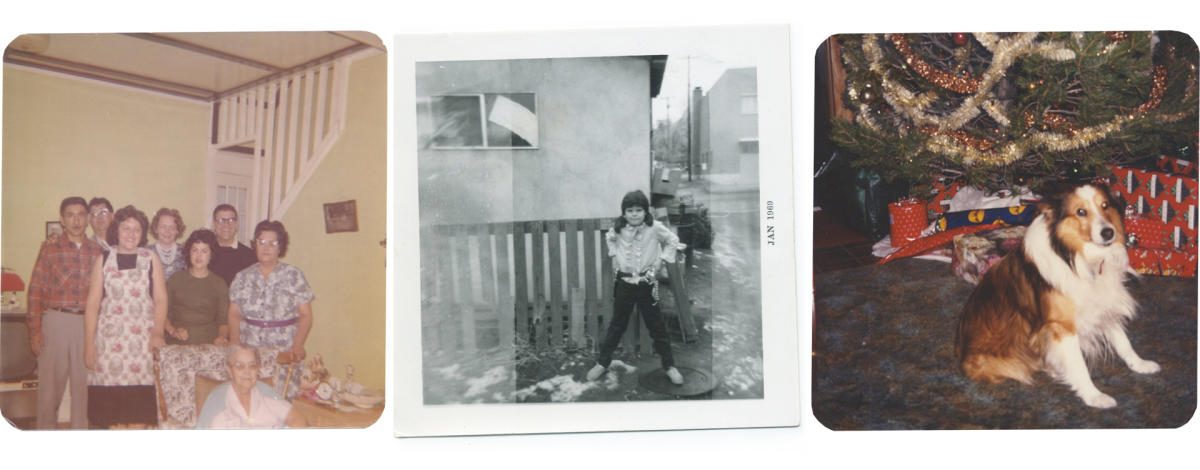

A family gathering in Las Vegas, New Mexico. The writer with that year’s favorite present, toy six-shooters. Rags waits for Santa. Photographs courtesy of Inez Russell Gomez.

EACH NIGHT, BEFORE I SLEPT, I would unplug my personal Christmas tree’s lights, turning down the electric fire that had brightened my night. Such lights, whether they’re the colored, static lights of my youth or the blinking white lights of my adulthood, underscore the point that, during this season, we all are waiting for the darkness to end.

For Catholic Christians, the promise of the baby is the light piercing the darkness. But all belief systems look for light in the bleakness of winter. It is our shared and very human condition to seek enlightenment metaphorically, through a candle, a fire, or a string of icicle lights.

On Christmas Eve, after a night of visiting relatives and then opening one present and one present only (pajamas, always pajamas), we would clean up and, just before midnight, walk the block from our house to Immaculate Conception Church, cutting through Jack’s Car Lot to make it to midnight Mass.

The best Christmases were those when snow was falling and the streetlights shone through swirling flakes to light our way.

In northern New Mexico, those lights become fire—the candle flame of farolitos in paper bags or the bonfires of the luminarias. (I know, I know, elsewhere in the state people call farolitos “luminarias” and luminarias plain old “bonfires.” But we northern New Mexicans appreciate a good tradition. Besides, we’re right.)

Nowhere is the light of fire stronger or brighter than in the bonfires at Taos Pueblo. They light the night with a fierceness that turns treacly Hallmark Christmas stories on their head. The fire of Christmas holds power. It roars to us that the darkness is temporary.

Great-grandmother Vicenta started the tinsel tradition. Courtesy of Inez Russell Gomez.

My family taught me to spread that light all season long. When we gathered to make food, spent time with family, trekked to midnight Mass, we were reminding ourselves that even in the darkness of winter, the light would come.

On that Christmas Eve when I decided to stay in Santa Fe, my heart was torn. My conscious mind did not accept it, but deep inside I knew. I was losing my mother.

That Christmas, we ate our traditional foods, prayed together at Mass, came home, and plugged in the lights on a very tiny, very fake tree—so untraditional. But we ladled out our red chile, grabbed a sopaipilla, and sat down for dinner. Together, we watched Jeopardy! It was our last Christmas together. It was the best Christmas ever.