THE CRISP DAWN LIGHT of mid-May sparkles as 20 or so Mescalero Apaches amble across the dusty Chihuahuan Desert in search of a thorny-leafed succulent called mescal. Some carry hatchets, others tote oak staves and sledgehammers, still others roll up their sleeves for the work ahead. Following in ancient footsteps, this harvest party’s job is to collect the tribe’s yearly bounty of mescal, which medicine man Nathaniel Chee reverently calls “the most valuable food of the Mescalero people.”

Ultimately bound for the reservation near Ruidoso, the fruits of today’s labor will be the star attraction during the next four days at the annual Friends of the Living Desert Mescal Roast, a public event held at the Living Desert Zoo and Gardens State Park in Carlsbad.

In the arid, ancestral wandering lands of the Mescalero Apaches, springtime’s awakening has long heralded the coming of harvest time for the plant coveted for centuries as the tribal staff of life. A staple source of nourishment with roughly the same food value as oats, the weighty heads of mescal were roasted, then eaten warm, or sun-dried and saved for lean seasons or as a C ration, of sorts, for times on the move.

Nothing was wasted. Mescal leaves provided fiber for woven articles, and tough leaf spears served as leather-piercing awls or razor-sharp weapons. So intimately entwined was the desertdwelling mescal with the lives of the Apaches who roamed where the plant flourished—the lower Río Grande and Pecos River valleys; the foothills of the Guadalupe, Sacramento, and San Andres mountains; and southward through west Texas into Mexico—that early Spanish explorers called the nomadic people mescaleros, or “mescal makers.”

Known to taxonomists as Agave neomexicana, the mescal plant is one of several species of agaves native to the Land of Enchantment. It blooms once during its 12- to 16-year lifetime—a far cry from the hundred years intimated by its misleading nickname, the century plant. In a matter of days, a 10- to 20-foot stalk shoots upward, then the plant quickly dies after a swan-song burst of striking orange-yellow flowers on high.

Through countless generations, language translations have so contorted the common names of many North American desert plants that it’s impossible to definitively say what it was when it comes to unscientific nomenclature like mescal, which in Spanish is actually spelled mezcal. What is known, for sure, is that the Mescaleros’ mescal (agave neomexicana) is not, as some folks think, the source of hallucinogenic mescaline, which derives from the button-like tops of the cactus commonly called peyote. Nor is it the plant from which tequila is distilled. That intoxicating beverage comes from agave tequilana, which grows in Mexico, where, to add to the confusion, several plants and drinks are called mezcal.

With such strong links between the Mescaleros and New Mexico’s mescal plant, it is no wonder that some tribal elders remain determined to continue the harvest and accompanying roast rituals. Their resolve has been difficult, for they face an immutable law of nature: Within the Mescalero Apache Indian Reservation, which spreads across the forested Sacramento Mountains, mescal plants are simply not abundant.

Pockets of them crop up in low-lying, dry canyons, but for the most part the species prefers much lower elevations. Since the reservation was established in 1873, most of the on-site plants have been depleted and the descendants of the early hunter-gatherers—who had a seemingly limitless supply of mescal—have either had to make harvest arrangements with private landowners in the arid foothills and beyond, or go without the sacred agave to which they owe their tribal name.

Eleven years ago, a conversation between an inquisitive state park employee and three women from the reservation became the stepping stone that infused new life into the mescal traditions, which were slowly falling by the wayside with each new generation. “One day I was driving through Mescalero and the spirit moved me,” says Mark Rosacker, wildlife culturist supervisor at the Living Desert Zoo and Gardens State Park in Carlsbad. He turned off the main highway and headed to tribal headquarters to ask about the age-old mescal heritage.

Those days, “we were doing a good job of introducing our visitors to the native plants and animals of the Chihuahuan Desert,” Rosacker recalls, but “the picture we were presenting was incomplete.” The people element had been omitted, and who better to consult than the Mescalero Apaches? “They’re the people with the most history here, the most knowledge, the most spiritual connection with the earth,” says Rosacker, who believed the time was right for park staff and visitors to broaden their understanding about the historic connections between the plants and peoples native to the desert whose fingers stretch across southeastern New Mexico.

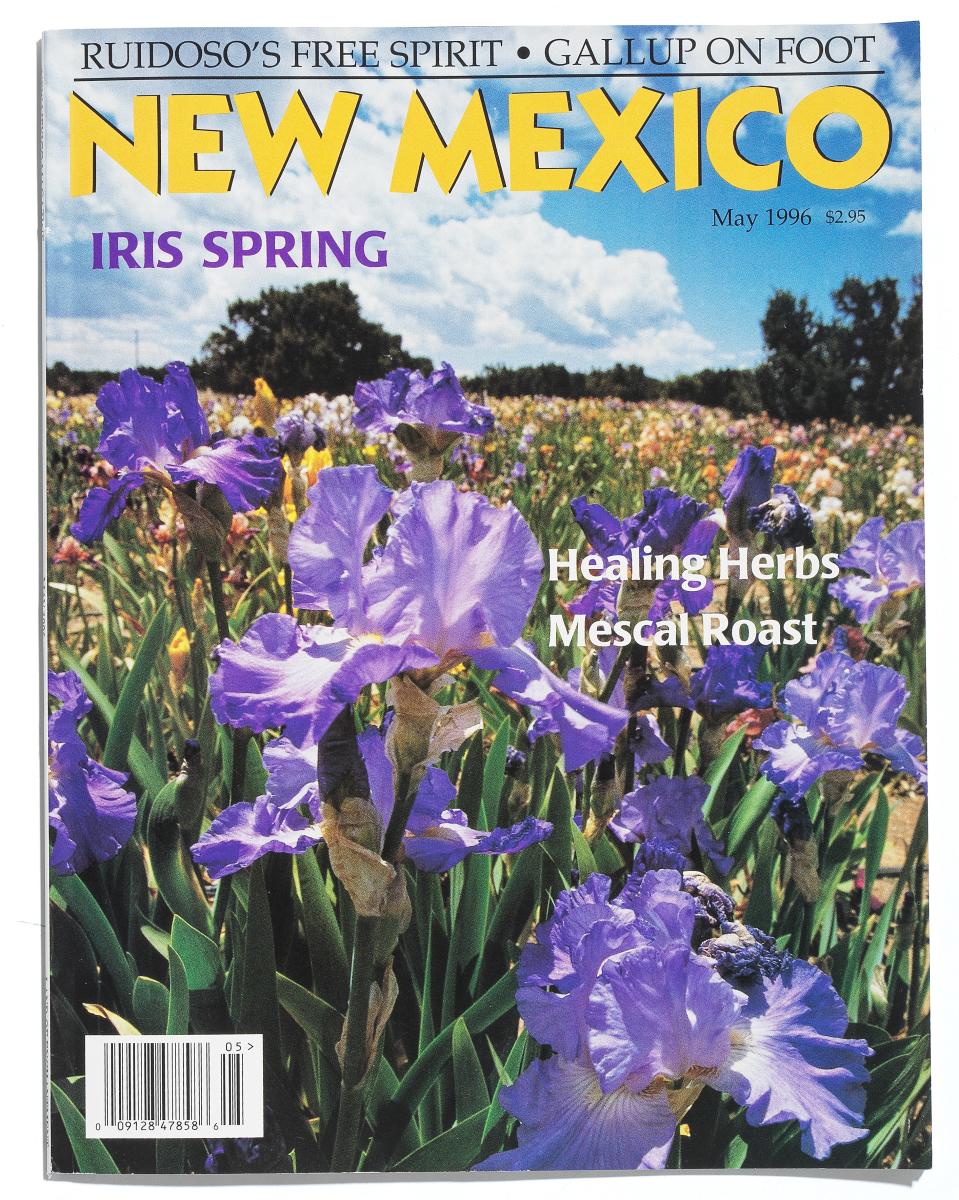

ON THE COVER

Russell Bamert shot our cover image of ‘Faded Denim’ irises at the Iris Ranch,

near Cerrillos.

So, too, was the moment right for revitalizing some time-honored Apache customs, according to the tribe’s traditional counselors who greeted Rosacker. Evelyn Martine, Mary Pefia, and Ellyn Bigrope welcomed him with a flood of generosity when he appealed for their guidance on behalf of the staff at Living Desert. “It’s a good thing that you asked,” Rosacker recalls one woman saying to him. Those words began an abiding relationship that has since touched the lives of the many Mescaleros and state park visitors alike who, over the past nine years, have participated in the annual Mescal Roast, sponsored by the park’s volunteer organization, the Friends of the Living Desert.

Once, mescal harvesting was a chore allotted to Apache women. Groups of 10 or 15 would venture on foot deep into the desert for weeks at a time, unlike today’s missions, which last a half-day at most. Now, the day before public events commence at the state park, a caravan of cars, pickups, and a tribal school bus transports Mescaleros, park staff, and invited others south from Carlsbad to a remote ranch across the Texas border.

On this particular harvest morning, the stark desert flanked by the Guadalupes is softened by the graceful crimson blossoms of countless ocotillos. An air of respectful quietude prevails as tribal elder and former traditional counselor Evelyn Martine leads the group with slow steps and serious intent, scanning the landscape for the first and most honored plant to be harvested.

Today’s occasion holds profound significance for Martine, for during the days to come, she will be accorded special honors in a ceremony at Living Desert that recognizes her role as “the guiding spirit behind the mescal roast” and praises “her dedication to Mescalero tradition and teaching.” And just weeks from now on the reservation, the plants gathered today will provide sustenance during the coming-of-age ceremonial in which her great-granddaughter Shirley Pefia will enter womanhood. Like many Mescaleros of recent generations, neither Shirley’s elder sister, Enid, nor her mother, Novaline Pefia—who is Martine’s granddaughter—experienced traditional puberty rites. Now, much to her heart’s delight, the centuries-old custom honoring females is returning to the family of Martine.

The 12-year-old girl stands alongside her great-grandmother, who chooses the first plant and softly whispers a prayer in her native language. Tribal medicine man Joey Padilla bestows blessings as he sprinkles mustard-yellow cattail pollen upon the mescal leaves. Then, as all watch in silence—for the taking of the first plant is a most sacred event—Shirley and her father, Seferino, share in the task of breaking free the mescal rosette from its roots. They wedge a four-foot oak stave into the pulpy base, then take turns pounding it with a sledgehammer until the plant topples over.

The mescal head is flipped upside down, then father and daughter begin chopping off the leaves with a hatchet. Around and around they encircle the plant, taking care to remove only the green outer portion of the 20-inch leaves and keep the bulbous, inner plant head intact. Customarily, bystanders pile the shorn leaves upon the exposed root as a rainwater catchment, hopefully ensuring that fledgling sucker plants emerge to encircle the spot where the parent once thrived.

Quotable

“If colors were audible, the foothills near Cerrillos would burst into a remarkable melody—vibrant, yet muted, strong but delicate—each May, when patchwork fields of radiant blossoms mingle with native vegetation on the grounds of the Iris Ranch.”

—from Iris Spring, by Pamela Porter

Small groups of people then scatter across the desert to repeat the traditional process, and by the time the sun is high overhead, 30 plant heads, some weighing nearly 40 pounds, are ready for the return trip to Carlsbad.

At midnight following the Wednesday harvest, oak wood is kindled at the park in a four-foot-deep, rock-lined roasting pit that is similar to the thousands of ancient mescal pits, called ring middens, which dot the surrounding region. Some dating back 8,000 years, these cooking spots are the best-known archaeological sites in the Guadalupes and the Pecos River Valley. By mid-morning Thursday, the coals are red-hot and a crowd of hundreds has gathered. Medicine man Nathaniel Chee, son of Martine, offers blessings. Then, as is customary, an Apache girl born in the springtime tosses the esteemed first-harvested plant head into the pit. Park employees and Mescaleros join together in placing the rest of the mescal heads onto the coals, then cover them with a layer of damp grama grass and some 20 inches of soil.

For the next 72 hours, while the mescal steam-cooks beneath the sealed earth, the park grounds pulsate day and night with a flurry of goings-on. The Mescal Roast is one of the “premier events” in the park system, according to Noe Villarreal, deputy director of New Mexico State Parks. In 1993, it received an outstanding achievement award from the Tourism Association of New Mexico. What’s unique, say Villarreal and others, is that the public, park staff, Carlsbad business community, and Mescalero Apaches unite to create this rare, cross-cultural sharing and learning opportunity that benefits Native and non-Native peoples alike.

Read more: The first chile feature by New Mexico Magazine describes the evolution of the chile.

Besides the roast itself, there are seminars about Mescalero customs, art exhibitions, and Native food and craft sales. Visitors can tour the impressive ecosystem-based plant and animal exhibits within the Living Desert State Park, one of the crown jewels of New Mexico’s park system. Friday and Saturday afternoons, powwow dances take center stage, and at dusk an Apache war dance precedes a traditional Mescalero feast prepared for the public. Before those evenings draw to a close, the atmosphere vibrates during the program’s keynote event: rare appearances by the elaborately costumed Apache dancers who perform the sacred Mountain Spirit Dances around a roaring bonfire.

On Sunday morning, a crowd gathers at the mescal pit to await the ceremonial unearthing of the steamed agave. After a solemn blessing, park staff, Mescaleros, and visitors heave shovelfuls of hot dirt from atop the pit, then the steaming, now-chestnut-brown mescal heads are lifted one by one out of the primitive oven.

Most will go to the reservation, the rest become nourishment for the crowd of young and old who gather to partake of the fruits of the harvest.

Outstretched hands receive piece after piece of the sticky mescal, which tastes as familiarly sweet as yams drenched in molasses, yet uncommonly earthy and new to the palate. The cooked plant is so fibrous that, after chewing for awhile and swallowing the soft portions, one must spit out the tough, rope-like quid, which someday should wind up recycled back into the soil.

“All of us, we come from this Mother Earth, and when we die we’re going to go back into this Mother Earth,” Chee says about the cycle of life so dramatically encapsulated in the age-old Mescalero rituals of respectfully harvesting, roasting, and consuming mescal. They are sacred traditions that are now returning, say tribal elders, who are heartened that the ways of the past are being embraced anew by the young.

BEES, A HONEY OF AN INSECT

On an early spring morning one can observe much activity around the beehive. All insects are coming to life, but the bees are the most numerous at one given spot, so you notice them the most. They are crowding out of the dark interior of their dwelling, launching themselves into the sunny air. I watch from a distance and have great respect for them … Recently I find more and more recipes that use honey in place of sugar, but I still like my honey best with fresh bread of any kind. –Adela Amador

- ¼ cup butter

- ¾ cup honey

- 1 egg

- 2 cups flour

- ½ teaspoon salt

- ½ teaspoon baking powder

- 2 tablespoons milk

- 1 cup chopped nuts

- 1 cup raisins, chopped

Makes 4½ dozen cookies

- Cream butter. Add honey and beaten egg and beat until fluffy.

- Sift flour, measure, and add salt and baking powder. Sift again. Add chopped nuts and raisins to flour mixture.

- Add dry ingredients alternately with milk to creamed mixture. Mix thoroughly.

- Drop by teaspoonful onto greased baking sheet, spaced 2 to 3 inches apart. Bake at 350° for 12 to 15 minutes.