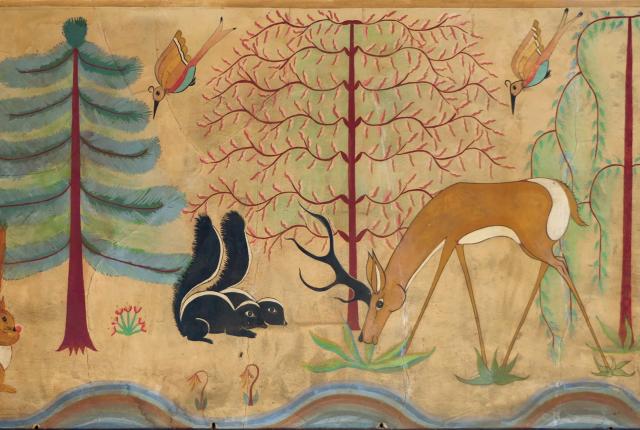

Pop Chalee’s Animals in the Forest. Courtesy of Historic Albuquerque.

A BLUE-SKINNED APACHE MOUNTAIN SPIRIT dancer in ruffled yellow pants hops on his moccasined foot. He brandishes two painted swords at his counterpart, a black-and-white-skinned dancer paused mid-stride. The Mountain Spirits’ traditional job is to usher Apache girls through a puberty ceremony. But these two figures stand sentinel in the entryway to the former Maisel’s Indian Trading Post, high above the windows of its elaborate Art Deco facade. For nearly 80 years, they greeted the thousands of shoppers who ducked into the famed emporium of Native American art, on Route 66 in downtown Albuquerque.

A young Harrison Begay focused on his Navajo tribe’s Yeibichai dancers in one of the Maisel murals. Courtesy of Historic Albuquerque.

Since the store closed last year, the spirit dancers have been off duty, as have the antelope hunters, rain birds, butterfly maidens, and deer dancers who stand three and a half feet tall in 17 murals that top the building’s double windows and the interior of its deep entry. The scenes of Native American life were painted in 1939, mostly by Pueblo, Apache, and Navajo artists who were art students at the time but went on to great renown.

Today the building stands vacant, its entrance secured with a folding metal security gate, but passersby can still see the two long panels of Pueblo and Navajo dancers outside the gate, on what is now Central Avenue.

San Ildefonso Pueblo painter Awa Tsireh depicted corn dancers. Courtesy of Historic Albuquerque.

It was the exposed dancers who occupied Diane Schaller’s mind in late May when a small group of rioters took to the downtown streets after a Black Lives Matter protest, setting fires and spraying graffiti across storefronts. Seeing the smashed plate-glass windows of the 94-year-old Pueblo Deco–style KiMo Theatre nearby shocked Schaller into action.

“We realized someone could come along with a spray can and ruin the murals,” she says. So she and the group she leads, Historic Albuquerque, quickly moved to document and assess the murals—just in case. Sooty from decades of exposure and a long-ago fire, the frescoes need restoration, Schaller says. The building’s new owner agrees.

“The building is a landmark, one of those properties that anybody who loves Albuquerque would be proud to own, but the murals are the most important thing,” says local auto-group managing partner Carlos Garcia, who bought the property from Skip Maisel when the longtime art dealer retired and closed the store in 2019.

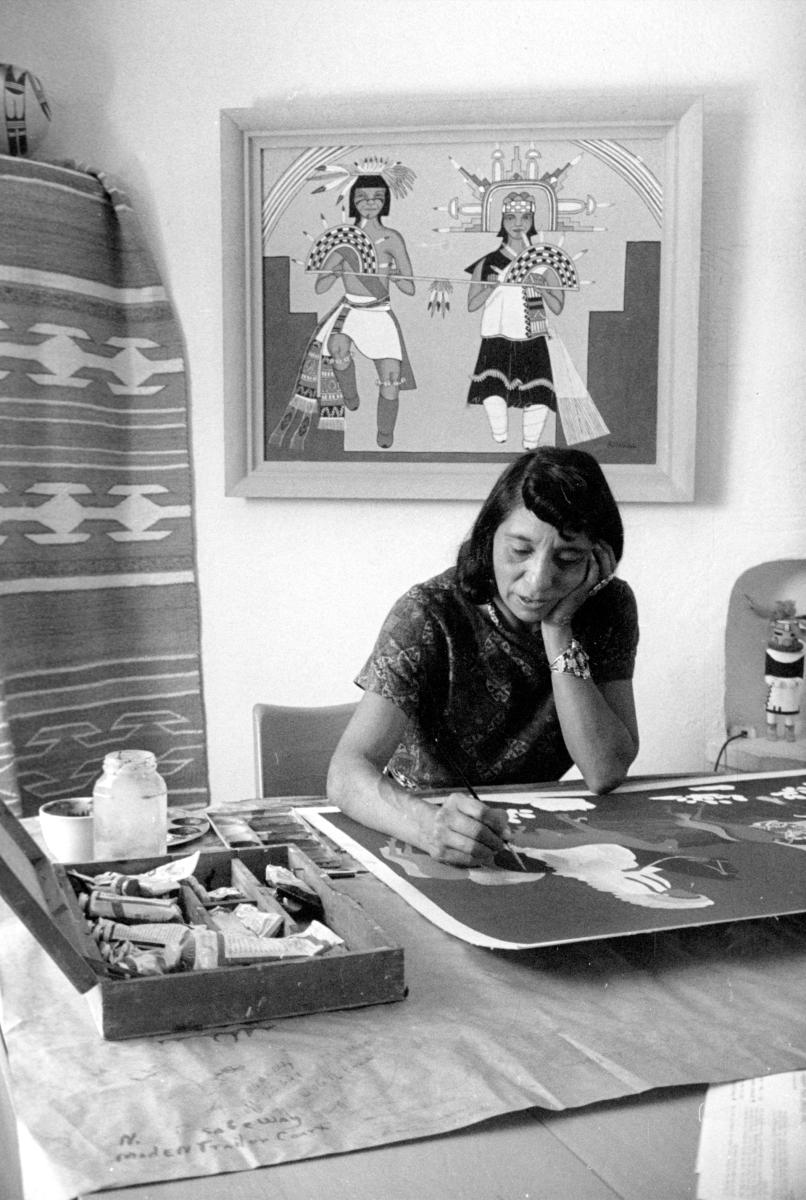

Pablita Velarde working at her home studio, in Albuquerque, in the 1960s. Photograph courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA) 174201.

Pablita Velarde, Pop Chalee, Harrison Begay, and Ben Quintana were among the 10 students and alumni chosen for the mural project, representing a mix of Puebloan, Diné, and Apache heritage. Today their works are held in major museums and sought by collectors.

“To have all of these murals on one building, by this group of artists, it’s like having a baseball autographed by the 1927 Yankees,” says Tony Chavarria, curator of ethnology at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, in Santa Fe. “That was the golden era of Native artists working in murals.”

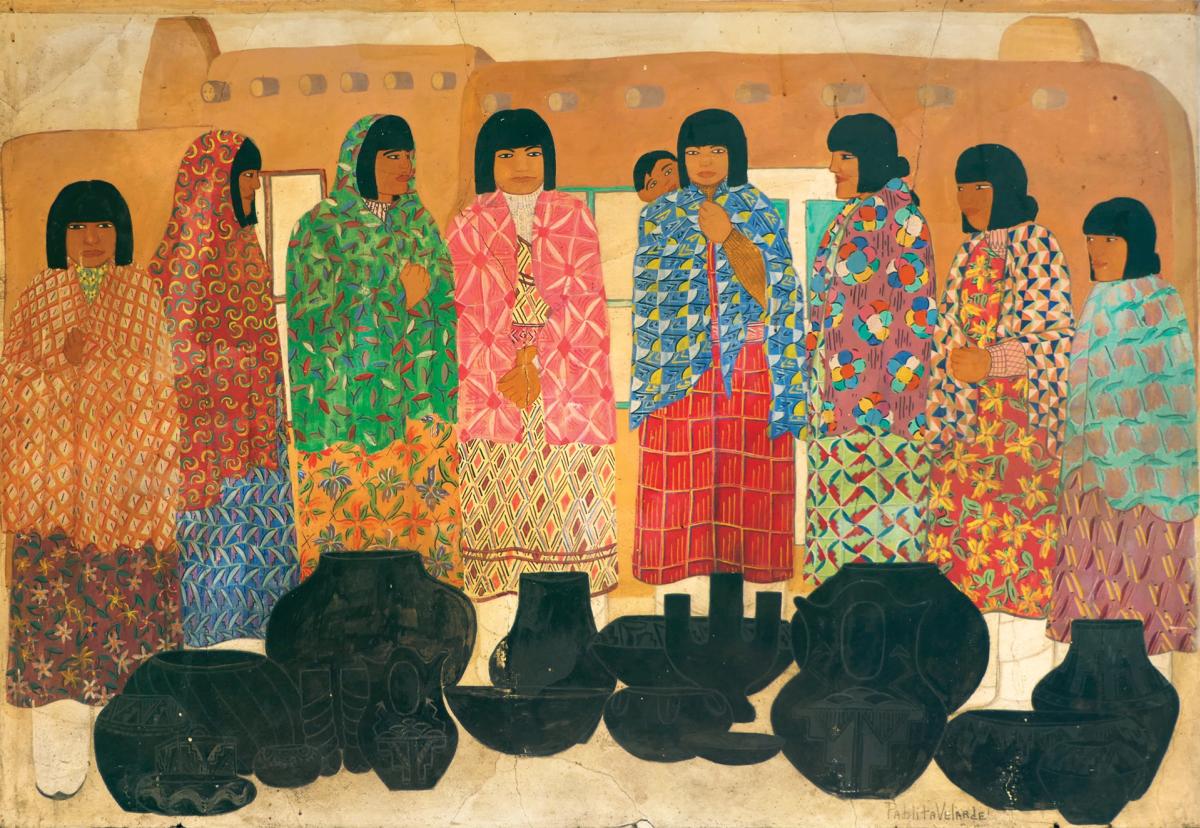

Pablita Velarde’s Santa Clara Women Selling Pottery. Courtesy of Historic Albuquerque.

It was valuable experience and exposure for some of the youngest artists, Chavarria says, including 16-year-old Popovi Da, who went on to collaborate with his mother, San Ildefonso Pueblo potter Maria Martinez. His painting on her pots brought new attention to her works and contributed to a profitable family business that lasted decades.

And yet many people have no idea these early murals exist. “They’re really important, but they’re not well documented,” says Paul R. Secord, a retired geologist and amateur historian who first saw the paintings 50 years ago as a student at the University of New Mexico and in 2018 produced a full-color paperback, The Maisel’s Murals, 1939: Native American Art of the American Southwest. “There isn’t a theme to the Maisel’s project, but it is a unified composition. It’s meant to compare and contrast these different aspects of Native American culture.”

Maurice and Cyma Maisel. Photograph courtesy of Historic Albuquerque.

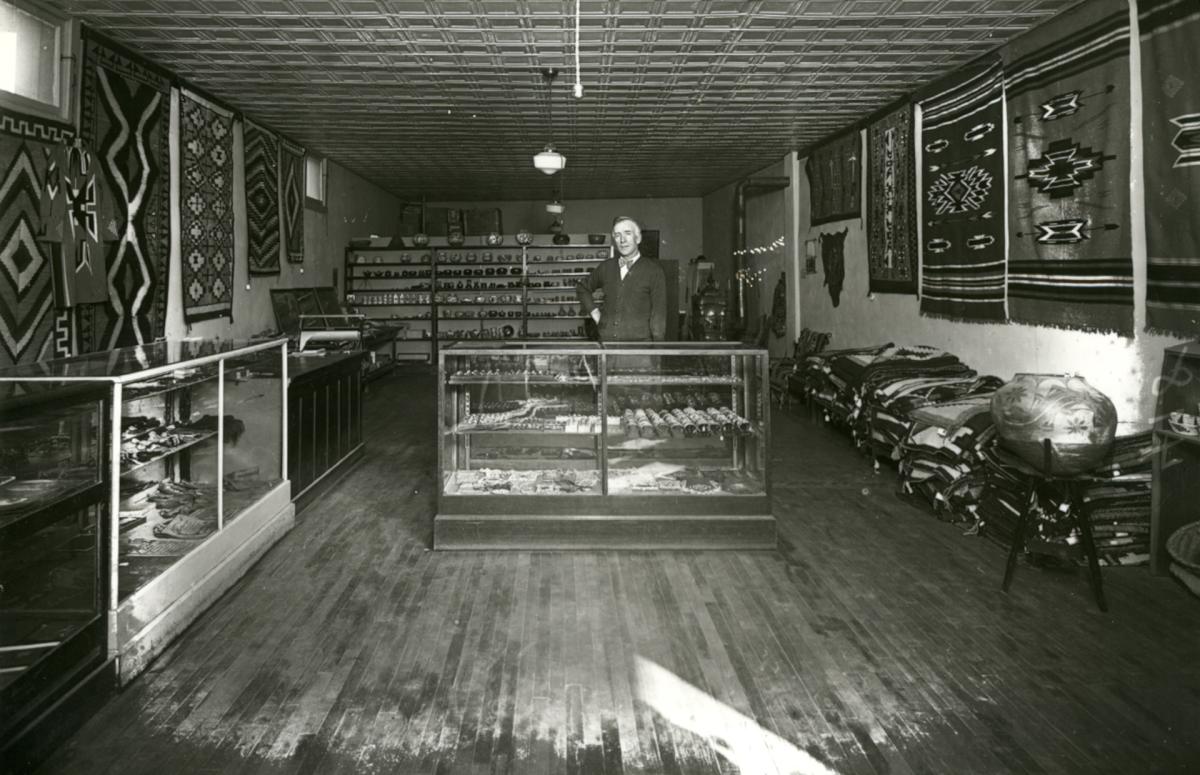

MAURICE MAISEL, THE DESCENDANT OF JEWISH refugees from Austria and Russia, made his way to Albuquerque from New York and earned his name and fortune by traveling the Southwest buying high-quality Native American jewelry and art. He sold the work at a trading post, to visitors who stepped off the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway's Southwest Chief, then later to those touring along Route 66.

It had several locations in Albuquerque, but in the mid-1930s he hired architect John Gaw Meem to design a modern structure for his newest store. Meem is best known for popularizing the Pueblo Revival style that came to define Santa Fe’s iconic adobe look, along with significant buildings on the UNM campus.

A prolific architect with varied tastes, Meem also designed a 1937 Streamline Moderne building directly across the street from Maisel’s.

Maurice Maisel at his 1930 store on First Street. Photograph courtesy of Albuquerque Museum, gift of Ray and Daniel Bandel, PA1977.131.005.

Meem hired Santa Fe–based artist Olive Rush, who had completed WPA murals throughout the Southwest, to adorn the building’s entry. But Rush had also been an art teacher at the Santa Fe Indian School—the famed “Studio School” started by Dorothy Dunn in 1932, which helped develop the skills of artists like Allan Houser, Andrew Tsinajinnie, and Gerónima Cruz Montoya. Rush devised a counterproposal for Meem: Let me bring in young Native American artists to do the murals.

The idea was subtly subversive.

“The first boarding schools here in New Mexico were about ‘creating productive citizens,’ meaning training Native people to do jobs on the lower rungs of society—housepainters, laundresses,” says Bruce Bernstein, a former executive director of the Santa Fe Indian Market who is now a curator at the Ralph T. Coe Center for the Arts.

The schools intended to erase Native culture and replace it with white culture. “Lately people have been calling that ‘systemic racism,’ which is good to hear out loud,” he says.

Muralist Olive Rush with portrait of Emma Beasley, taken when Rush received an honorary doctor of arts from Earlham College, Richmond, Indiana, ca. 1947. Photograph courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA) 019272.

But the 1930s brought changes to the curriculum at Indian schools, including professional training programs in the arts. Those programs, Bernstein says, told students that “you can be an artist and stay at home, in the village, you can still participate in your community life, you can still maintain your fields. It was exactly what the government didn’t want, but it’s what they did.”

Teachers like Rush looked for ways to demonstrate the viability of art as a profession. Her students painted images for posters advertising the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago, and by the time Meem approached Rush for his project in Albuquerque, she had already collaborated with students on a series of murals in the cafeteria at the Santa Fe Indian School.

Olive Rush’s Pueblo Family Gathering Corn. Courtesy of Historic Albuquerque.

Searching through the Olive Rush papers, at the Smithsonian Institution’s Archive of American Art, for his book, Secord found documentation of how much the artists were paid. Meem had a budget of $1,500. The painting took about two weeks, and Rush paid the 10 students and alumni $5 a day, at a time when the minimum wage was less than $2.50 per day. Two already established artists who joined the group were paid a flat fee for their work: Awa Tsireh earned $91 for Pueblo Corn Dancers, while Rush kept $500 for the three panels she painted and her management of the project.

“In a way, the murals are very forward-thinking,” Bernstein says, because they were done by Native artists who were fairly paid, and because they were done on a store, not as part of a government project. The style of painting may have been one standardized by teachers at the school, but “on the other hand, what you see—100 percent untouched by any white person—is the subject matter, which Rush did not dictate.”

Maisel’s store on Central Avenue in the 1940s. Photograph courtesy of Albuquerque Museum, gift of Jeff McDaniel, PA2007.017.065.

BY THE 1940S, MAISEL'S STOOD AS ROUTE 66's largest trading post, employing more than 300 Native craftspeople on-site. Their works were tailored to what tourists wanted—a long-standing issue for critics of trading-post culture—but also provided jobs into the 1960s, when Maisel died and the store closed. His grandson Skip opened it as Skip Maisel’s Indian Jewelry & Crafts in the 1980s. In 1993, the store earned a listing on the National Register of Historic Places.

Over the past decade, Secord befriended Skip as the grandson prepared for his own retirement. “People had been pestering me to do a book about the murals,” Secord says. “So I thought, I’ve got to do this now, because I don’t know what’s going to happen when the store closes.”

Garcia was mindful of that legacy when he purchased the building, one of several historic properties he and his family own downtown, including the Southwest Brewery and Ice Co. building. The pandemic has slowed his plans for repurposing Maisel’s, but Garcia says he’s willing to take his time to find the best use.

Tony Martinez (Popovi Da) painted Straight Beak Bird and San Ildefonso Butterfly Maiden for his murals. Courtesy of Historic Albuquerque.

No matter what happens to the structure, Historic Albuquerque wants to be prepared. That’s why, on a hot afternoon this past summer, as dozens of young artists were at work painting murals on other, boarded-up windows along Central, photographer Dan Shaffer perched on a ladder, pointing his lens at Animals in the Forest, by Pop Chalee. It includes two wide-eyed skunks, a bushy-tailed squirrel, a pair of diving birds, and a Bambi-like deer. (It’s oft told, though not proven, that Walt Disney got the idea for Bambi from her work.) At seven feet across, the painting was too long to capture in just one click. As was Narciso Abeyta’s 27-foot-long Navajo Ceremonial Antelope Hunt.

“The paintings are terrific, and for a private building to have done that is amazing,” Bernstein says. “They should put in the effort to restore them.” He points to similar projects from the era. Two large murals Zuni artist Tony Edaakie painted in a conference room at the De Anza Motor Lodge, on Central Avenue in Albuquerque, in 1951 were saved when the motel was mostly razed for a mixed-use development. And three earth-pigment panels by Pablita Velarde that had been displayed in the Western Skies Hotel, also on East Central and also razed, were successfully restored and are now displayed in the Roundhouse in Santa Fe.

Joe H. Herrera’s Cochiti Butterfly Dancers. Courtesy of Historic Albuquerque.

Today, most of the murals at Maisel’s are relatively safe, locked behind their security gate. “Some of them look like they just need to be cleaned,” Garcia says. “Others might have a little damage, but they’re actually in a lot better shape than I thought.”

He’s committed to finding the right person or team to do the work.

The photographs taken by Historic Albuquerque went to an image-processing firm to be stitched together, Schaller says. She plans to give a copy of the prints to the building’s new owner. Garcia says he’s a big fan of Historic Albuquerque, which has helped him research other buildings, and that he’s open to collaborating on architecture tours or other careful ways of sharing the murals.

For Route 66 enthusiasts, modernist architecture aficionados, and John Gaw Meem fans, the building remains a destination on any tour of Albuquerque. To others, the murals mean a lot more.

“The cultural arts—jewelry, pottery, baskets—are very alive, and they’re very needed to sustain cultures,” Bernstein says. “These murals are everybody’s history—they’re about the survival of Native people.”

WHERE TO FIND THE MURALS

The former Skip Maisel’s Indian Jewelry & Crafts is at 510 Central Ave. SW, in Albuquerque.

NATIONAL EXPOSURE

Mural participant Awa Tsireh has a ca. 1918 watercolor painting in Picturing the American Buffalo: George Catlin and Modern Native American Artists, a special exhibition at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian through May 2, 2021.