SMALL ENOUGH FOR HER fingers to close over it, the pendant resting on Martha J. Egan’s palm demands a closer look. It bears an image of the Virgin Mary in absolute miniature. “In Copacabana,” she says, referencing the art form’s Bolivian artisans, “they make paintbrushes out of mouse hair, a horse’s eyelash, a cat’s whisker.” The result is as magnificent as an Old Master’s rendering, but double-sided, with an equally detailed image on the pendant’s verso.

Once prominent in Spanish colonies, most especially those in South America, Mexico, and New Mexico, these relicarios lost favor during 19th-century independence movements. Tossed away, fashioned into something else, or relegated to jewelry boxes, they escaped the notice of art historians and antiquarians. Except for Egan.

The longtime owner of Pachamama Gallery, which specializes in Latin American masks, milagros, textiles, furniture, and jewelry, Egan stumbled across enough samples to produce a 1993 book, Relicarios: Devotional Miniatures from the Americas. She quickly learned how much she still needed to know.

“I realized I had made some mistakes,” she says while sitting at a deeply carved wooden table at Casa Perea Art Space, a mid-19th-century hacienda in Corrales that houses the latest outpost of Pachamama. “Some that I had thought were old were modern reprints. What I had been told was silver was actually pot metal. Other people might not care, but I did.”

Martha J. Egan holds a large relicario.

Martha J. Egan holds a large relicario.

She dedicated herself to deeper research, building relationships with far-flung artists and traders and scouring church records, colonial inventories of goods that traveled on El Camino Real, scholarly articles, even WPA-era oral histories—anything that might give a whisper of a mention to these two-sided emblems of faith.

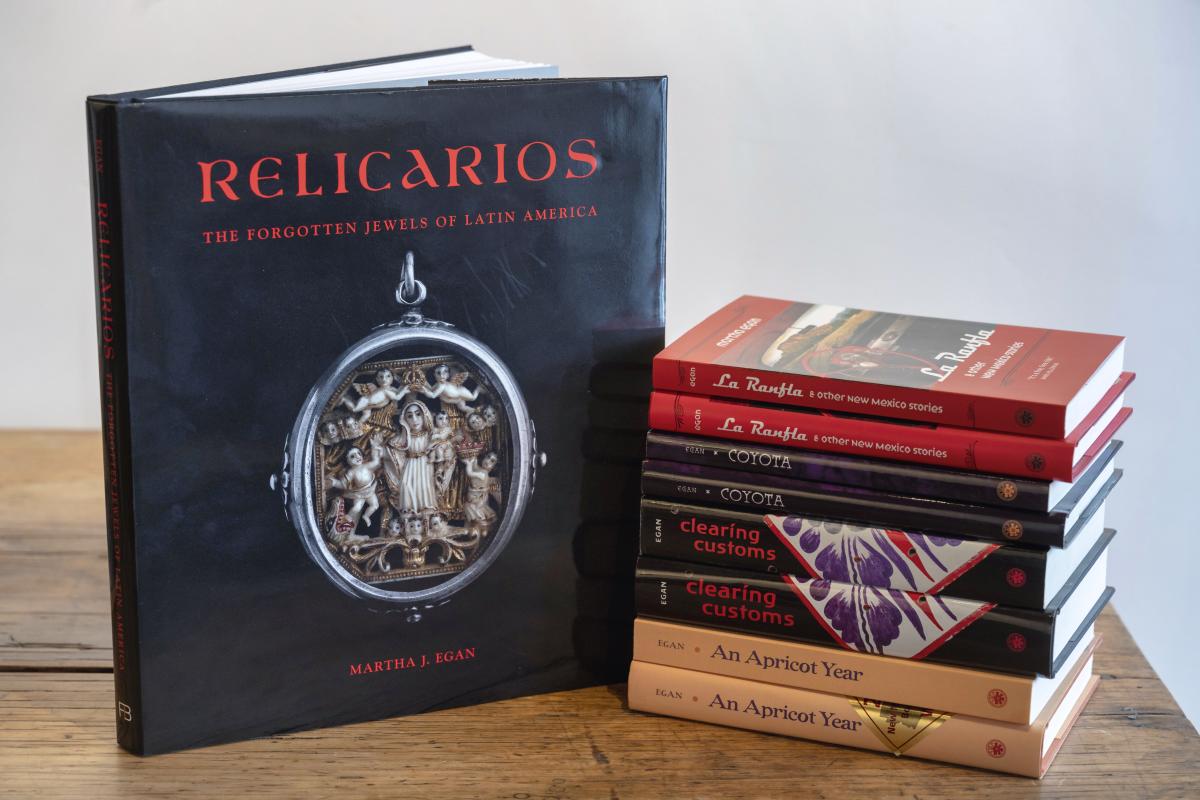

She reveals the results in a new book, Relicarios: The Forgotten Jewels of Latin America (Fresco Books), a beautifully illustrated and rigorously annotated history.

“The book is so comprehensive,” says Spanish colonial art historian Josef Díaz, who has curated exhibits at the New Mexico History Museum and the Museum of Spanish Colonial Art, both in Santa Fe. “I was floored. I always knew there was religious jewelry, but it was through Martha that I started to learn about these in particular, as devotional pieces and as beautiful artworks.”

Collectively, the relicarios, sometimes called medallones, miniaturas, and camafeos, reveal a vast range of stories—the demands of obeisance to Spain’s crown and cross under the searing eye of the Inquisition, the spread of artisanship among colonists and Indigenous peoples, the souvenir desires of pilgrims to South American religious sites, and the Manila galleons weighted with so much ivory, some intended for painstakingly carved pendants, that the ships could founder and even sink.

Pachamama Gallery carries Latin American imports (dog not included).

Pachamama Gallery carries Latin American imports (dog not included).

“These were luxury items that came up from Mexico on the caravans,” Egan says. “People with money wanted Manila silk shawls and other special things. The relicarios were prized family heirlooms. They were passed down through the generations, especially among women, because they were so isolated here. They had a real relationship with the Virgin. The relicario was how you showed your loyalty to La Virgen or to Saint Joseph, to your personal guardian. They were powerful amulets.”

The earliest and most precious versions bore painted images or ones that were carved in ivory, horn, mahogany, or other rare woods. The Copacabana artisans became masters at images as small as a fingernail. Sometimes a converso, a converted Jew, would sandwich something Hebraic between the two sides, outwardly professing the “correct” religion while hanging on to a part of Spain’s forbidden culture.

“By the late 1700s, the movement for independence in Mexico was growing, and as part of it, there was a lot of anti-church sentiment,” she says. “The relicarios went into grandmothers’ lockboxes and were forgotten about. All kinds of paintings show people wearing them, but the art historians skipped right past it. I started looking and asking.”

It wasn’t easy. Beyond getting locked up, such pieces sometimes broke, Díaz notes. “Things wear out,” he says, “or they come apart, and maybe you melt them down to make a different piece of jewelry.” Some antique dealers realized they could turn one pendant into two by mounting each image on its own one-sided setting.

Pachamama Gallery is located at Casa Perea Art Space, a mid-19th-century hacienda in Corrales.

Pachamama Gallery is located at Casa Perea Art Space, a mid-19th-century hacienda in Corrales.

Egan was well suited to the hunt, Díaz says. “She’s built relationships with people all over Mexico and South America,” he says. Few could have predicted that career for a lapsed Catholic raised in small-town Wisconsin, but Egan fell in love with Latin American history during college, obtained a degree in it, and immersed herself in further studies, including working with Jesuit Basques during a Peace Corps stint in Venezuela. When her sister and brother-in-law, Polly and John Arango, started Pachamama in Albuquerque, she set out to find imports for them and eventually bought the business.

“One thing that was immediately popular were the milagros,” she says of the small metal amulets of arms, legs, hearts, and anything else in need of healing. “I must have been asked 5,000 times, ‘What’s a milagro?’ ” So she wrote a book about it. Milagros: Votive Offerings from the Americas remains in print, and as Egan likes to say, at the store today, “milagros are us.”

Read More: Vintage Fred Harvey jewelry finds new life at Peyote Bird Designs.

As she renewed her research into relicarios, Egan slowly amassed pristine colonial examples from South America and Mexico, particularly in Mexico City, which she proclaims has “the best flea market of anywhere.” Along the way, she found 19th-century versions with photographed images replacing the handmade ones, and a few latter-day fakes.

“I’ve been had,” she admits. “But I kept asking wherever I went, and someone would open a drawer and pull out a couple.”

She uncovered evidence of an early-20th-century artisan in Peña Blanca, a village south of Santa Fe, who placed two-inch rectangular prints into his handmade tin frames. She also began encouraging contemporary New Mexico santeros like Charlie Carrillo and Ramón José López to render new ones.

Bernadette Caraveo, a Spanish Market santera who has also worked with Egan for years at Pachamama, first in Albuquerque, then in Santa Fe, and now in Corrales, was surprised when she recalled her grandfather having kept a relicario in his pocket.

Martha J. Egan in the sala of the Casa Perea Art Space, which holds a bounty of antique furniture and textiles.

“I never knew that’s what it was,” she says. She then began working with Arturo Olivas on new versions: He painted the images; she crafted the silver casings.

Egan’s favorite source of information was Jerónimo Quero Sosa, a Zapotec weaver and muleteer, whose many trading missions to remote villages high in the mountains made him a cultural interpreter of the significance a small pendant could hold among the faithful.

“He had the information I couldn’t get from anyone else,” she says. “Why it was still important there, which women were allowed to wear one. There’s no shopping up there, so when a girl got married, she was given a family relic.”

With her knowledge, along with the relicarios—some of which are for sale at Pachamama—Egan hopes to mount a museum exhibit exploring the jewelry’s importance as a marker of history, religion, and culture.

“In a way, these are like icons for getting into the cultural history of Latin America,” she says. “They came out of a medieval tradition and they reveal the ivory trade, the teaching of silversmithing skills, a host of craftsmanship that is dying out.”

Relicarios: The Forgotten Jewels of Latin America

Relicarios: The Forgotten Jewels of Latin America can be purchased at the Pachamama Gallery, along with other books by Martha J. Egan. The store is open Wednesday through Saturday, 10 a.m.–5 p.m., or by appointment. Pachamama nestles inside the elegant Casa Perea Art Space, which will again host concerts, weddings, and other events when it’s safe. 4829 Corrales Road; 505-503-7636.