Wings of America runners hit the trail at Rinconada Canyon, on Albuquerque’s west side.

"GOOD MORNING, CREATOR." The voice of Dustin Martin, executive director of Wings of America, rises over his team—a collection of the nation’s fastest Native American high school runners. Hands in hoodie pockets and legs shivering in their shorts against the cool January morning, the runners bow their heads as he continues. “Thank you for giving me the experience and the knowledge to share these hills with these young people. These hills have taught me who I am and where my strengths lie. I wish the same for them.”

He looks up, his gaze skipping among runners who traveled from Oklahoma, North Dakota, the Navajo Nation, and pueblos throughout New Mexico to attend this Albuquerque training camp. “The wind is going to challenge us today,” he says. “We’re going to want to slow down. But we have each other to keep us going.”

The team sets off, the crunch of their footsteps on the rocky trail quickly fading as they disappear into the Sandía Mountains foothills. Each time they reemerge from their mile repeats, Martin matches the runners step for step, completing the loops alongside them. Seniors Galvin Curley and Jasmine Turtle-Morales often lead the pack. A turquoise nugget bobs against Curley’s chest as a remembrance of his miles with fellow Native runners at Bears Ears National Monument. Turtle-Morales, a coach in the making, is always encouraging her teammates.

Since 1988, Wings of America runners have sped to 32 team titles at the USATF National Junior Olympic Cross Country Championships, and alumni have topped leaderboards as some of the top athletes in the country. But running, for this organization, has always been about more than split times and first-place medals.

For these students, running is a pathway to connect more deeply with their heritage, to break free from the grip of grim statistics, and to become leaders in their communities and beyond.

“Wings is always about running,” says Martin (Diné), a former Wings team member himself. “But it’s also about telling young people about a beautiful tradition. Running helps them gain a connection with culture.”

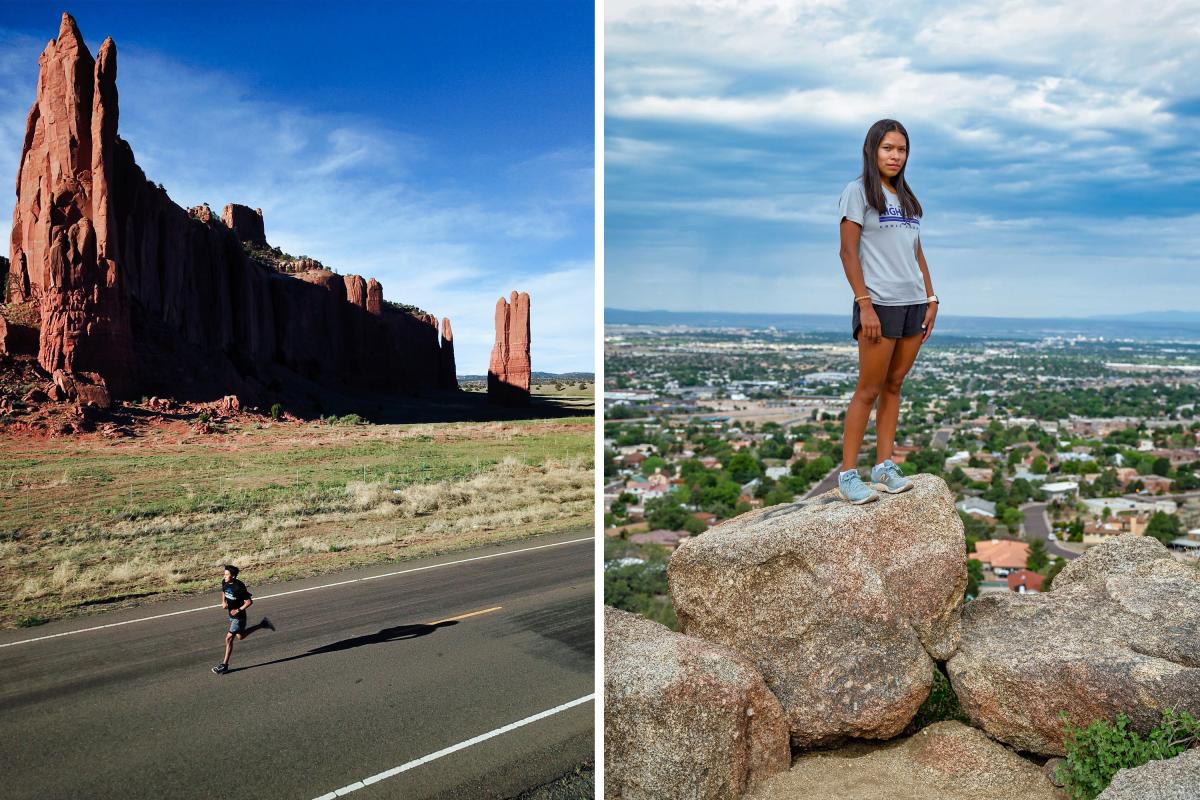

Galvin Curley runs through Bull Canyon, on the Navajo Nation (left), Jasmine Turtle-Morales in the Sandía Mountains (right).

Galvin Curley runs through Bull Canyon, on the Navajo Nation (left), Jasmine Turtle-Morales in the Sandía Mountains (right).

SANTA FE-BASED WINGS OF AMERICA, the sole beneficiary of the nonprofit Earth Circle Foundation, sponsors a handful of running programs for Native people throughout the U.S., including a coaches’ clinic and running and fitness camps for youths from tribes and pueblos in New Mexico. Its Boston Marathon Pursuit Program pairs running with a look at college life, taking promising high school juniors on a weekend trip to Beantown for “a cosmopolitan worldview during one of the most exciting running weekends in the world,” Martin says.

The Wings national team is its flagship program. Martin and his staff recruit runners during their high school cross-country seasons. Students must show tribal affiliation. Those who achieve the best times can qualify for travel support to regional qualifying meets for the national championships, held each January.

Some of the all-time great Native American runners have been Wings team members. Alumni include Felicia Guilford (Hopi), an All-American who led her University of Tennessee team to a national track-and-field title; Jackson Thomas (Diné), who finished his college career in 2017 as the NAIA Men’s Outdoor Track & Field National Championships MVP; Alvina Begay (Diné), who competed in the 2008 women’s marathon Olympic Team Trials; and Dillon Shije (Zia Pueblo), who as a high school junior in 2008 was considered the top Native American runner in the country and was featured in the 2010 documentary Run to the East.

For New Mexico runners in particular, Wings provides a springboard to college athletic scholarships and the opportunities university study affords. Since runners here often compete at elevation (sometimes above 7,000 feet), their times are slower than those of runners at sea level. New Mexico athletes need race times from regional and national events to

attract the attention of college recruiters. “This gives kids that shot when they wouldn’t get it otherwise,” Martin says.

But they aren’t running just for college scholarships. “What we create is beyond competition,” Martin says. For one, running can be a path to physical and emotional health. As a group, Native American people experience the highest rates of suicide of any racial or ethnic group in the U.S., and youth suicide is 2.5 times higher than the national average. Life-threatening Type 2 diabetes is also more prevalent among Native American communities than other groups.

Wings runners may have a better chance than others of avoiding those statistics. “They connect their spiritual well-being to their physical well-being,” Martin says. “They develop community and support through running.”

However, he warns, even that good news can turn into a tired stereotype. “I hope we’re getting to a period now to appreciate the success of Native runners, and we don’t always make their success a rags-to-riches story.”

For Indigenous people, he notes, cultural and spiritual practices are embedded into running. Although traditions differ, tribes from throughout the U.S. often share the belief that running is sacred. “Running isn’t to exert dominance over someone,” Martin says. “Native running is a prayer for other people and the land.”

Jasmine Turtles-Morales and Dustin Martin stretch after a run.

Jasmine Turtles-Morales and Dustin Martin stretch after a run.

ON ANOTHER WINTER MORNING during training camp, the runners gather on Albuquerque’s west side at Rinconada Canyon, part of the Petroglyph National Monument, where the trail traces a mesa etched with markings from Ancient Puebloans. Today’s practice pays homage to a 2018 run, organized by the Bears Ears Prayer Run Alliance, also through sacred lands. In that event, runners from the Hopi, Navajo, and Ute tribes, as well as a few New Mexico pueblos, ran 800 miles through the Four Corners states to call for protecting Bears Ears National Monument’s full acreage for Native peoples. Martin and Curley (Diné) were among the runners. “It wasn’t about the miles we were running,” Curley says. “It was about the prayers we were saying.”

Prayer runs are familiar to the now 19-year-old. Curley, who hails from Navajo, New Mexico, a town that hugs the western edge of the state, grew up in the shadow of a towering red-rock butte. As his cultural traditions teach, he would rise before the sun, face the east to pray, then run. “I pray for well-being for myself and my family,” he says. “Running shows the Holy People you’re committed to your prayers.”

Curley’s predawn runs often take him on a six-mile loop through his town of about 1,600 people. Sometimes he heads to Bull Canyon, where rock monoliths dwarf his lithe form as he strides back to town, past the lines of beige tract houses bordering the two-lane blacktop. “When I’m running, I’m just putting one foot in front of the other,” he says. “I look at the canyon, feel the wind blowing, hear the birds. I forget everything.”

He races the sun home, stretching his stride to beat the light over the top of the butte.

Galvin Curley at his home in Navajo, New Mexico (left), Turtle-Morales leads the pack (right).

Galvin Curley at his home in Navajo, New Mexico (left), Turtle-Morales leads the pack (right).

Curley started running in second grade to get fit for basketball—another of Indian Country’s top sports. The youngest of nine children, Curley grew up always losing to brothers and sisters who were stronger and faster. Hating to lose pressed him to champion-level bona fides, including state individual cross-country titles his junior and senior years, finishing as the top New Mexico competitor at the Nike Cross Nationals Southwest Regional, and being named the Gatorade New Mexico Boys Cross Country Runner of the Year in 2019–20.

More than his individual titles, he’s proud of his three state titles with his team from Navajo Pine High School. “Sharing success with others is better than just getting it yourself,” he says. “Winning with the team, you get to share the moment with the people you grind the season out with.”

Running has opened doors for Curley—to college and to the broader meaning of being a Native runner. Wings helped him realize his dream as an NCAA Division I college athlete. He’d planned to run for the University of Arizona Wildcats this fall, before the Pac-12 Conference postponed all sports through the end of 2020 because of COVID-19. “He’s done the work,” Martin says. “Wings just gave him the pathway.”

Over the summer, Curley and some friends organized a running club for kids. “I try to show the kids what running can do. I’m always trying to get them to just run a lap with me,” Curley says. “If they do, it might change the way they think.”

Dustin Martin gathers the team for a blessing before a foothills run in Albuquerque.

Dustin Martin gathers the team for a blessing before a foothills run in Albuquerque.

WHEN SHE WAS A THIRD GRADER, a few laps after school sparked a transformation for now 19-year-old Jasmine Turtle-Morales (Cochiti/Mescalero Apache/Hopi).

She entered the foster care system when she was five years old. Three years later, Aysha Turtle adopted her. The family is reticent to dwell on Turtle-Morales’s past, but Turtle, a longtime foster mother, says that her daughter’s case was the worst she’d seen. The child struggled in school. At one point, her behavior was so poor that Albuquerque Public Schools wouldn’t let her be in a classroom with other children. Turtle homeschooled her until she won her way back into class.

“No one thought she had a chance to make it through school and do well,” Turtle says of her daughter, who has since earned a scholarship to New Mexico Highlands University.

In running, Turtle-Morales found something she did better than everyone else. “When she runs, something just kicks in,” says Gary Sanchez, her stepfather and a former cross-country coach. “Running is just in her heart and soul. It’s not like anything I’ve ever seen.”

Her confidence soared as she joined a private running club in middle school and earned a spot on Albuquerque’s Eldorado High School cross-country team. With the Eagles, she finished first in the state in 2018–19 and second in 2019–20. Her efforts led her team to back-to-back state titles. She never once missed practice because of grades or behavioral concerns. And when she earned the 2018–19 Gatorade New Mexico Girls Cross Country Runner of the Year award, she donated the $1,000 grant to Wings. (Curley likewise gave his grant to Wings when he won this year.)

Turtle-Morales found a family and a passion in the sport. She knew her tribal affiliations but couldn’t prove her tribal enrollment. Wings made an exception for the talented runner; the staff felt she would benefit both from the coaching and from being around other Native runners.

Until then, she didn’t have much connection to her roots. But during her second year, the team visited a pueblo for dinner during training camp. Seeing feast day dances tugged at the fuzzy edges of Turtle-Morales’s childhood memories. “I remembered that I did that, too,” she says. “I didn’t remember exactly, but I felt the old ways. I felt like I belonged there. Wings brought my culture back.”

She has found other connections at meets. Across New Mexico’s tribal and pueblo lands, running is popular. In the state’s larger cities, Native American coaches and runners often lead teams. Native families pack the stands and line the course during the state cross-country meet. At one such competition, a Native elder came out of the stands to tell Turtle-Morales, “Show the Native American nation what you’ve got.”

“That really touched my heart,” she says.

As the senior Wings runners headed off for their first semesters in college this fall, Martin continued to look at life beyond the competition. An NCAA Division I athlete at Columbia University, where he graduated summa cum laude, Martin saw for himself how priorities shift. “I don’t love how fast speed is equated to worth when you compete at a high level,” he says. Working for Wings during college summers before he became part of the full-time staff “kept me aware of the good side of running.”

So, as he trains the next team, he’ll keep reminding them, too: “Do this for yourselves, but keep your ancestors in your minds. And always find strength for future generations.”