WHERE CR 279 BREAKS SOUTH from US 550, between San Ysidro and Cuba, centuries of history emerge. The craggy knob of Cabezón Peak, the remnant of a 1.5-million-year-old volcanic eruption, looms to the east as the road passes through the village of San Luis. After turning into a well-maintained dirt road, it forks this way and that before reaching the village of Guadalupe and then a parking area for a Bureau of Land Management site, Guadalupe Ruin. A short climb up a trail leads to a 12th-century Chacoan outlier, later occupied by Mesa Verde refugees and then again by the Gallina people.

The land below splays out in a panorama of sheer cliffs and broken arroyos. Noted folklorist and author Nasario García grew up exploring all of it. His grandfather was among the last residents to leave Guadalupe, after the once verdant Río Puerco had withered into a deep arroyo.

Today, García’s family home is an eroded adobe among other eroded adobes, including a rare two-story building that some ghost-town chasers contend was a brothel. Which makes García laugh. “They would have been run out of the village,” he says. The real occupants, the Córdova family, lived on the second floor and ran a mercantile on the first. So far as miscreants go, consider the behavior of young Nasario and his cousin Juan during dances held at the store.

“Juan and I were in charge of sprinkling water on the dirt floors, especially after a polka, to settle the dust,” García says. “The men would go outside for a hidden bottle of wine. As the night progressed and they got drunker, Juan and I would add more and more water. Think of them trying to get all that mud off their boots!”

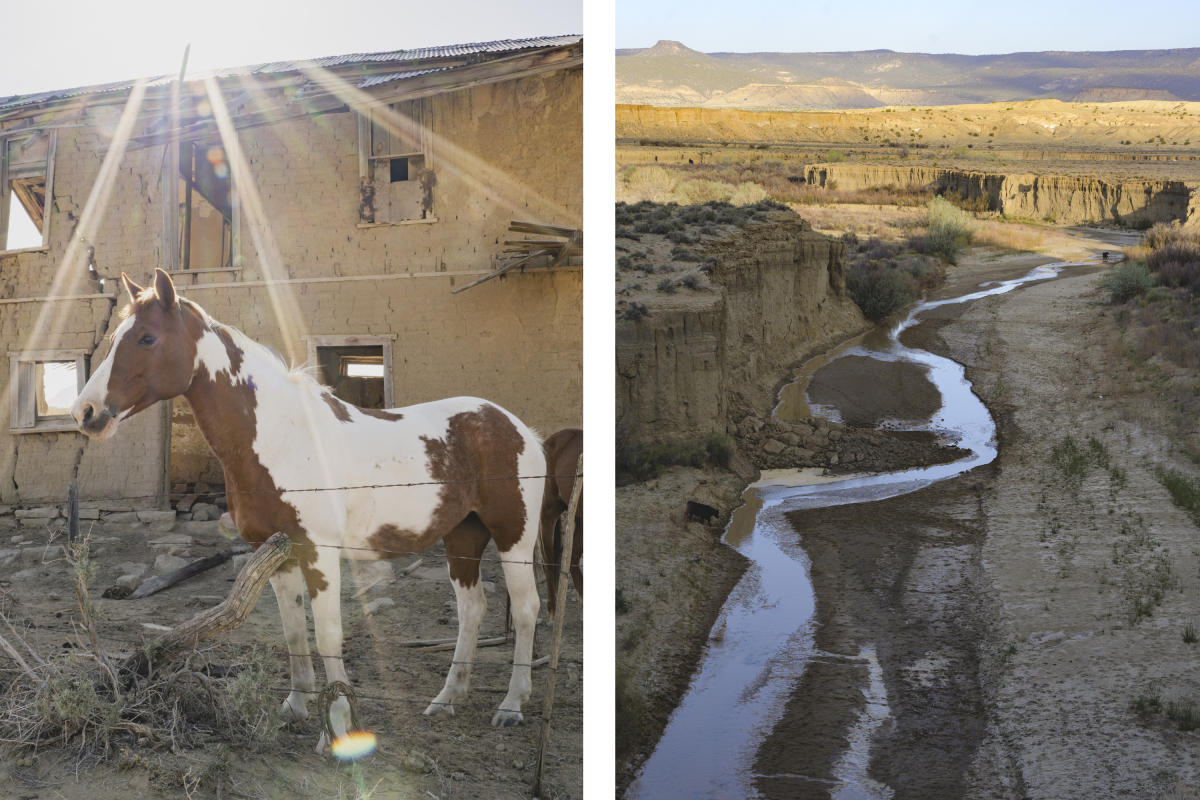

Horses at the old Córdova store in Guadalupe (left). The Río Puerco once nourished the villages (right).

Horses at the old Córdova store in Guadalupe (left). The Río Puerco once nourished the villages (right).

García has collected such tales in several books, including his acclaimed Hoe, Heaven, and Hell: My Boyhood in Rural New Mexico. He’s a cherished elder among others with family ties to the area, including Lorraine Dominguez Stubblefield, president of the Sandoval County Historical Society. Her family roots lie in San Luis, where the San Aloysius Gonzaga chapel still holds occasional services.

“All the villages back there—San Luis, Guadalupe, Cabezón, Casa Salazar—everyone was related to everyone,” she says. “Today there’s probably 25, 35 people who live there on a weekday, maybe 45 on a weekend.”

Cabezón village is gated and requires permission, but San Luis and Guadalupe can be seen from the road. (Obey private property signs.) Casa Salazar, south of Guadalupe, requires a rugged vehicle.

The people of San Luis hold the deed to the chapel and maintain it themselves, along with a morada for the laypeople who provide community guidance and a historic cemetery.

During Holy Week, it becomes a pilgrimage site. “This last year, my brother, who’s 74, he did a promise for my nephew, who has colon cancer,” Dominguez Stubblefield says. “He walked from the highway to the church. That’s always a beautiful time of year.”